Occupying Public Space, 2011

From Tahrir Square to Zuccotti Park

Karen A. Franck and Te-Sheng Huang

over the course of 2011, thousands of people in cities around the world occupied public space in political protest. In democratic societies and repressive authoritarian regimes alike, citizens made their concerns internationally known through their extended, joint physical presence in central urban squares and plazas. In some cases, the demands were specific, such as the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak in Egypt or the ouster of the monarchy in Bahrain; in Spain and particularly in the United States, the issues of concern were multiple and diverse. In nearly every case, local police or the military eventually forced the demonstrators to leave. In all cases, at least some violence occurred and demonstrators were injured; in the Middle East, demonstrators died. The occupying of public space in 2011 for political ends at the risk of arrest, injury, and worse, demonstrates how public space can still become “loose” (Franck and Stevens 2007) or “insurgent” (Hou 2010).

In this essay, we compare four urban spaces that were occupied in 2011: Tahrir Square in Cairo; Pearl Square in Manama, Bahrain; Plaça de Catalunya in Barcelona; and Zuccotti Park in New York City. We briefly look at their histories, their design features, and the activities they hosted in 2011. Then we take a more detailed look at the design and use of Zuccotti Park. In all four cities, the intensive, creative use of urban public space as a tool of political action was remarkable. While virtual communication via social media was essential to the planning and ongoing coordination of the demonstrations, the presence of significant numbers of demonstrators in a single physical space played an equally important role, particularly for reaching a much larger, international audience. While communicating to the public and to each other was essential, occupying public space over time also required that demonstrators organize the space and the provision of shelter, food, and security. As shown in the images of Zuccotti Park, communication and the tasks of daily life occurred side by side.

Communicating and food distribution, Zuccotti Park, New York City. Photos by Karen Franck (above) and Te-Sheng Huang (below)

Four Occupied Spaces

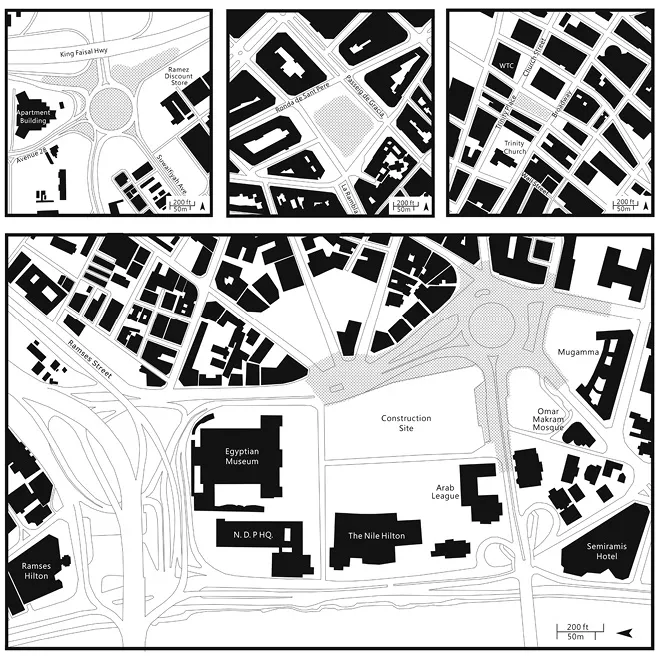

Of the four public spaces described in this essay, Tahrir Square in the center of Cairo is the largest, functioning as a transit hub for metro, buses, and cars. A great many streets lead to the square from different parts of the city. Its form is loosely defined and comprises several different spaces, including a very busy traffic circle and a large construction site. Significant buildings—the headquarters of the Arab League and of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party, the Hilton, and the Omar Makram Mosque—border the space without enclosing it. A grassy plaza in front of the Egyptian Museum was once a popular meeting place but in the 1970s was enclosed with a construction fence as a means of subdividing the space and preventing assembly (Elsahed 2011).

Inspired by Hausmann’s modernization of Paris, Khedive Ismail established the square as an open space in 1865 in his efforts to modernize Cairo (AlSayyad 2011). The square has long been the site of political protest: in 1919, Egyptians demonstrated against British rule and again in 1946 and 1951. Further demonstrations were held in 1977 against rising food prices, in 2001 in sympathy with the Palestinian Intifada, in 2001 against the US invasion of Iraq, and in 2006 in solidarity with Lebanon under attack from Israel. All these demonstrations involved significant risk, and many resulted in injuries and death; none lasted long (Taher 2012).

Left: Pearl Square, Manama, Bahrain, Feb. 14–Mar. 16, 2011. Center: Plaça de Catalunya, Barcelona, May 15–June 29, 2011. Right: Zuccotti Park, New York City, Sep. 17–Nov. 15, 2011. Bottom: Tahrir Square, Cairo, Jan. 25–Feb. 11, 2011. Occupied Public Space in Manama, Barcelona, New York City, and Cairo. Courtesy of Google Maps, Google Earth, and Thompson 2011

In January 2011, as many as three-hundred thousand demonstrators and possibly more gathered in the square on particular days and, despite the risks of injury and death, maintained their hold on the space. To protect themselves from anti-Mubarak forces, the occupiers barricaded streets to the square and operated checkpoints to review people’s identification cards and to search for weapons. People waited in two lines to pass through these check points: women in one, to be searched by women, and men in the other, to be searched by men. After newcomers passed through the checkpoint on Ramses Street, occupiers warmly welcomed them with cheers and singing. Since February 11, when Mubarak was ousted, the square has continued to be site of demonstrations.

In February 2011, Pearl Square, also called Pearl or Lulu Roundabout, was a grassy traffic circle accommodating four large roads in the heart of Manama, the capital of Bahrain, located close to the central market, the marina, and a large apartment complex. Its iconic status arose from the monument built on the traffic circle in 1982 to honor the first summit meeting of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) to be held in Bahrain. The towering Pearl Monument was composed of six curved beams representing the six members of the council which held, at the top, a large cement pearl symbolizing Bahrain’s history of pearl cultivation. At the base was a pool. The monument became a symbol of Bahrain, appearing on its half-dinar coins (Reisz 2011).

On February 14, Pearl Square, as one of Bahrain’s largest and most symbolic spaces, was a good site for demonstrators to gather and demand the ouster of the country’s monarchy. After a bloody crackdown by the city police on February 17, the protestors were allowed to return, staying until March 16 when Bahrain Defense forces along with military forces from the GCC and Saudi Arabia evacuated and bulldozed the encampment. On March 18, the monument was razed; then the traffic circle was removed and replaced with traffic lights, eliminating any space for gathering that was free of cars. To remove any semantic association between the former square and the protest movement, the new space was renamed Al Farooq Junction. On February 14, 2012, security forces prevented marchers from returning to the junction, which remains cordoned off. Into 2012, subsequent protest marches have filled major streets in Bahrain but were prevented from reaching the new junction (AJE 2011; Mitchell 2011a).

Like Tahrir Square, Plaça de Catalunya functions as a traffic hub in the center of Barcelona, being the starting point for two of Barcelona’s major streets (La Rambla and Passeig de Gracia) and hosting a great many bus lines and, below ground, four metro lines and one regional train station. Also like Tahrir, it was envisioned as part of an urban modernization plan in the mid-nineteenth century although it was not built until the twentieth century based on the design idea of Josep Puig I Cadafalch (Permanyer 2011).

Its design, however, is radically different from Tahrir’s, being a clearly defined open space enclosed by streets and monumental buildings on all sides. These buildings include the department store El Corte Ingles, banks, hotels, and the historic Café Zurich. Unlike many European squares, the center of the plaza is open. Fountains and sculptures, mature trees, and some grassy areas are located around the periphery, leaving the central paved area empty, encircled by benches.

Starting on May 21, 2011, the plaza, along with public spaces in cities throughout Spain, became a site of a movement variously called Real Democracy NOW or the Indignants, which responded to problems of unemployment, increased costs of education, reductions in social benefits, and political corruption. Plaça de Catalunya is regularly used for political demonstrations (with permits), and is where thousands of fans of the Barca football team gather to celebrate victories. It was the expectation of such a celebration on May 28 that police gave as a justification for forcefully clearing the square of demonstrators on May 27, using rubber bullets and truncheons and injuring many. After the square had been cleaned, protestors returned and, with signs reading “No to violence,” blocked access to many rowdy and often violent football fans (Tremlett 2011). Occupiers remained in the square until police moved them out in late June.

Of these four spaces of revolution, Zuccotti Park, the original site of the Occupy Wall Street movement, is the ...