![]()

Chapter 1

Ivan’s Inheritance

The Muscovite state which Grand Prince Vasilii III bequeathed to his infant son Ivan IV in 1533 was a comparatively recent formation, created by the annexation of neighbouring north-eastern Rus’ principalities by the grand princes of Moscow. It was also only comparatively recently that Muscovy had established its independence from the Tatars who had exercised suzerainty over the Rus’ lands since the thirteenth century.1

The dynasty of the grand princes of Moscow traced its origins back to the semi-legendary figure of Ryurik the Viking, who had in the ninth century been invited by the peoples of what is now north-western Russia to come and rule over them. In due course the Ryurikids (Ryurik’s descendants) became the princes of the land known as Rus’, which was inhabited predominantly by eastern Slavs. Their capital city was Kiev (in present-day Ukraine), and their state is thus frequently described as Kievan Rus’. In the tenth century it extended from Kiev in the south to Novgorod in the north; it subsequently expanded eastwards, to Nizhnii Novgorod on the River Volga, and to the foothills of the Ural Mountains.

In the thirteenth century the lands of Rus’ were invaded from the east by the Mongols, a nomadic Asiatic people also known as the Tatars. Their military campaigns of 1237–40 were led by Batu, a grandson of Genghis (Chingis) Khan. In December 1240 the Mongols captured Kiev, before continuing westward into Poland and Hungary. Batu built his capital at Sarai, on the lower Volga, and the Rus’ lands were incorporated into his realm, the Kipchak Khanate, which has become better known as the Golden Horde. With the construction of Sarai, the ruling élite of the khanate became settled and urbanised; and in the fourteenth century the Horde adopted Islam. The official language of the Horde was Turkish, reflecting the extensive assimilation of the original Mongol invaders to the indigenous Turkic peoples of the steppes.

By the time of the Mongol invasion, Kievan Rus’ had acquired a complex political structure. The grand prince, the senior member of the Ryurikid dynasty, was based in Kiev. From the time of Yaroslav ‘the Wise’ (d.1054) the other main towns were allocated to junior members of the dynasty on a hierarchical basis which (in theory, but not always in practice) determined the order of succession to the Kievan throne. From 1097 these towns were recognised as the capitals of separate principalities which were passed down within the same branch of the dynasty. In subsequent decades some of the principalities became increasingly independent of Kiev. One of these more independent principalities was Suzdalya, to the north-east of Kiev, which expanded and prospered in the twelfth century. Often known as Vladimir-Suzdal’, its major towns were Rostov, Suzdal’ and Vladimir, all of which served at various times as its capital. The town of Moscow, in the south-west of Suzdalya, is mentioned for the first time in 1147, in the reign of Prince Yurii Dolgorukii.

The Mongol invasion reinforced the growing division between the south-western and the north-eastern lands of Rus’. Kiev itself was severely weakened, and ceased to serve as a focal point for all the Rus’ principalities. In the course of the fourteenth century the western and south-western lands – Polotsk, Turov, Volynia, Galicia, Smolensk, Chernigov, Pereyaslavl’ and Kiev itself – came under the control of Poland and Lithuania, while the north-eastern principalities, including Suzdalya, remained part of the Golden Horde.

In spite of the political separation of the north-eastern principalities from the south-western lands, religion remained a unifying factor for the peoples of Rus’. Kievan Rus’ had adopted Christianity in 988, with the conversion of Prince Vladimir I. Vladimir adopted his new religion in its Eastern Orthodox form, from Byzantium (Constantinople), and Rus’ continued to have close relations with the Byzantine Empire throughout the Kievan period. Prince Vsevolod Yaroslavovich married a relative of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX Monomachus; their son, who became grand prince of Kiev in 1113, was known as Vladimir Monomakh. After the Mongol invasion, Kiev at first remained the ecclesiastical centre of the lands of Rus’; in 1299, however, Metropolitan Maksim, the head of the Church, moved from Kiev to Vladimir. In 1325 Metropolitan Peter took up residence in Moscow, which became the official seat of the metropolitan in 1354.

Although Mongol domination was for a long time described by Russian historians as the ‘Tatar yoke’, the overlordship which the khans of the Horde exercised over the Rus’ lands mainly assumed the form of the exaction of tax or tribute. From the fourteenth century, the Rus’ princes themselves acted as tax-collectors and administrators for their Tatar overlords. The Mongols asserted the right to appoint the princes, who had to travel to Sarai to receive the khan’s yarlyk or letter of confirmation. In 1243 the khan granted Prince Yaroslav Vsevolodovich of Vladimir the titles of grand prince of Kiev and grand prince of Vladimir; thereafter, Vladimir replaced Kiev as the dominant principality of the Rus’ lands. In general the Mongols respected the rules of dynastic succession to the grand princely throne which had operated in the Kievan period. In 1328, however, rivalry between the Tver’ and Moscow branches of the dynasty for the position of grand prince was resolved by the khan in favour of the latter. Prince Ivan Daniilovich of Moscow became grand prince of Vladimir as a result of the khan’s patronage, even though he had no legitimate claim to the throne according to the traditional principles of succession. Ivan I (nicknamed ‘Kalita’ or ‘Moneybags’, because of his financial acumen) was therefore more dependent on the Mongols than his predecessors had been. Ivan Kalita and his heirs made frequent visits to the Horde; this custom familiarised the grand princes of Vladimir with Mongol methods of rule and administration, and may have inspired them to adopt similar practices in their own domains.2

The period of Mongol domination is often described as the era of ‘fragmentation’ of the Rus’ lands. Not only did it witness the separation of the south-western principalities around Kiev from the north-eastern territories of the grand princes of Vladimir, but in the north-eastern lands themselves the principalities were increasingly subdivided. Vladimir-Suzdal’ was split into Vladimir, Suzdal’ and Rostov, which were in turn broken up; Beloozero and Yaroslavl’, for example, were carved out of Rostov. These smaller principalities, which were inherited within a single branch of the dynasty, were known as appanages (udely) – a term which is sometimes used to characterise the period as a whole.

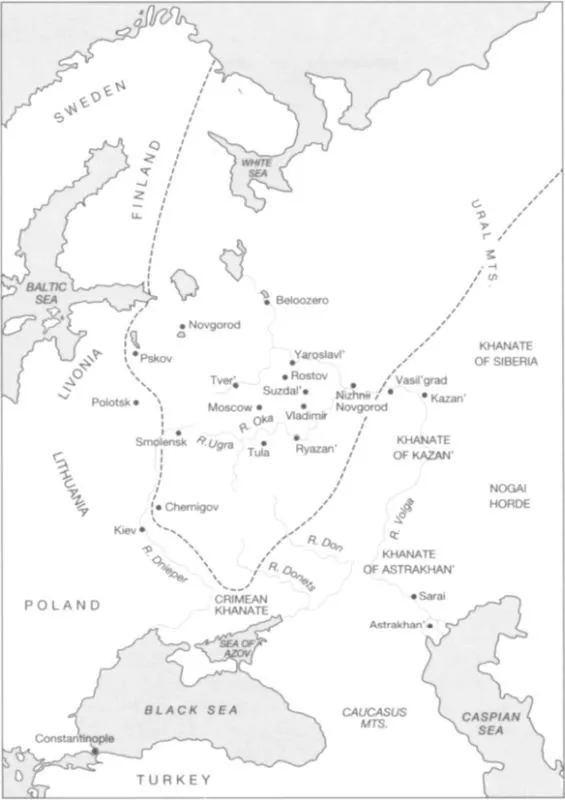

After Ivan Kalita became grand prince of Vladimir, however, the principality of Moscow began to expand through the annexation of neighbouring principalities. This process, commonly known as the ‘gathering of the lands of Rus”, continued under his successors. Ivan III (1462–1505) annexed the great city of Novgorod, with its extensive northern hinterland, and added the principality of Tver’ to his domains. His son, Vasilii III (1505–33), incorporated Pskov and Ryazan’. At the death of Vasilii III, Moscow not only ruled all of the north-eastern lands which had formed part of the Golden Horde, but as a result of wars with Lithuania it had acquired some of the territory of the Chernigov and Smolensk principalities of Kievan Rus’, including the important fortress of Smolensk itself (see Map 1.1). With this westward expansion Muscovy acquired a population which included some of those east Slav peoples who were subsequently to become known as Belorussians and Ukrainians.

Map 1.1 Muscovy in 1533

By this time, Muscovy had emancipated itself from Mongol overlordship. In the middle of the fourteenth century the Golden Horde began to experience a number of internal crises which were to lead to its disintegration. Its main offshoots were the Crimean khanate, on the northern shore of the Black Sea, and the khanate of Kazan’, on the mid-Volga. The remainder of the Golden Horde, which became known as the Great Horde, retained its base on the lower Volga, although its capital, Sarai, never recovered from its devastation by the Mongol warlord Timur (Tamerlane) at the end of the fourteenth century. The Rus’ princes took advantage of the discord within the Horde in order to challenge their Mongol overlords. In September 1380 Grand Prince Dmitrii Ivanovich led a coalition of princes that defeated the Tatar warrior Mamai at Kulikovo, on the upper reaches of the River Don. Dmitrii, who gained the epithet ‘Donskoi’ from his victory, did not however succeed in overthrowing the suzerainty of the khan, who continued to dominate the lands of north-east Rus’. As the Golden Horde disintegrated, however, Moscow became more self-assertive. A confrontation on the River Ugra which took place in October 1480, between Grand Prince Ivan III and Akhmat Khan of the Great Horde, is often said to have marked the definitive end of the Tatar yoke’. In practice the grand prince was by this time an independent ruler, although he continued to pay tribute to the Mongols even after 1480. Following the destruction of the Great Horde by the Crimean Tatars in 1502, Ivan III sent the payments to the Crimean khan, but it was now little more than a token gesture.

By the reign of Vasilii III, the Great Horde had been succeeded on the lower Volga by the khanate of Astrakhan’; the steppes further east were dominated by the nomadic Nogai Horde; and to the north there lay the khanate of Siberia. These successors of the Golden Horde were fragmented and disunited, and they posed little threat to Muscovy. On the mid-Volga, the khanate of Kazan’ was more formidable, but its relations with Russia were fairly stable. The greatest potential danger was presented by the Crimean khanate. Since 1475 Crimea had been a vassal of the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire, which had continued to expand, after its conquest of Constantinople in 1453, to the northern shores of the Black Sea. The Russians feared that in any conflict with the Crimean khan, the latter would receive the support of his master the Sultan.

At the time of the ‘stand on the Ugra’ in 1480, Ivan III had formed an alliance with the Crimean khan, Mengli-Girei, against the combined forces of Akhmat Khan of the Great Horde and King Casimir IV of Lithuania and Poland. The Muscovite association with Crimea expanded to include Kazan’, when in 1487 Russian troops helped to place Mengli-Girei’s stepson, Magmet-Amin’, on the Kazanian throne. After the death of Ivan III, however, the alliance with Crimea was weakened. Mengli-Girei’s successor, Magmet-Girei, sided with Poland-Lithuania in its wars against Russia, and in 1521 the Crimean Tatars attacked and besieged Moscow itself. The conflict between Moscow and Crimea was exacerbated by rivalry between them for influence over Kazan’. In 1523, after the murder of a Russian ambassador to Kazan’, Vasilii III constructed a new fortress, named Vasil’grad (later Vasil’sursk) on the River Volga, just within the territory of the khanate, and in the following year he sent an army against Kazan’ which overthrew the Crimean client Saip-Girei. Saip-Girei was replaced as khan by another Crimean prince, Safa-Girei, and the outcome represented a compromise which lasted until 1532, when Safa-Girei was deposed by the Kazanians and replaced by a Moscow candidate, Enalei.

In order to counter the growing threat from the Crimean Tatars, in particular, the grand princes began to strengthen their southern frontiers with chains of fortresses. With the annexation of Ryazan’ in 1521, Vasilii III gained control of key strategic territory bordering the ‘wild field’ of steppelands that lay between his realm and the Tatar khanates to the south and east. In the late fifteenth century the River Oka had constituted the southern frontier of Muscovy; the fortification of the town of Tula, between 1509 and 1521, brought the defence line further south. On the steppe grasslands beyond the frontier there roamed bands of cossacks, mounted warriors who may have originated as offshoots of the Tatar hordes, but soon included many ethnic Slavs, fugitives from Poland and Lithuania as well as from Muscovy. They frequented the basins of the rivers which drained into the Black Sea and the Caspian – the Dnieper, the Don, the Volga and their tributaries – and supported themselves by fishing, piracy and brigandage. By the mid-sixteenth century some cossacks provided regular military service to Muscovy along its southern and eastern borders, while others remained free agents on the steppes.

At the same time as the grand princes of Muscovy were establishing their political independence from the Tatars, the Russian Church was becoming increasingly free of Byzantine influence. Until the fourteenth century, the Russian metropolitans were appointed by the patriarch (the head of the Eastern Orthodox Church) in Constantinople. After the death of Metropolitan Fotii in 1431, however, the patriarch delayed naming his successor. During the interregnum Bishop Iona of Ryazan’ acted unofficially as head of the Church, and in 1436 he was officially nominated by Grand Prince Vasilii II as the new metropolitan. The patriarch, however, promptly appointed his own candidate, Isidor. At this time, the Byzantine Empire was under attack from the Ottoman Turks, who were threatening Constantinople itself. The emperor and the patriarch, hoping for military assistance from Catholic Europe, responded favourably to an approach from the pope concerning the re-establishment of Christian unity. Soon after taking up his new office, Metropolitan Isidor left Moscow to attend the Council of Florence, which was convened in 1437 to negotiate the re-unification of the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches. When Isidor eventually returned in 1441 to report that the Council had agreed to the union of the two Churches, he met with a hostile reception from the grand prince and the Russian bishops, who deposed him as metropolitan. In 1448 they named Iona of Ryazan’ as his successor. When Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453, the immediate reaction in Moscow was that God had punished the patriarch and the emperor for their heretical acceptance of union with Rome.

In appointing Iona as metropolitan without the approval of the patriarch, the Russian Church had effectively established its independence from Byzantium. The Church in Constantinople survived the capture of the city by the Turks, but it was now subject to the political authority of the Sultan. The fall of Constantinople meant that the decisions of the Council of Florence were largely a dead letter, and Moscow’s breach with the patriarch was soon mended. But Ivan Ill’s emancipation of his state from Tatar overlordship contrasted with the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks: Russia was now the only major Orthodox realm which was independent of non-Orthodox rulers. In 1472 Ivan III had married Zoe (Sofiya) Paleologue, a niece of the last Byzantine emperor, thus establishing a degree of dynastic continuity with Constantinople. It was in this context that the idea developed that Moscow was the spiritual heir to Byzantium. The best known version of this notion is the concept of ‘Moscow the Third Rome’, which we shall discuss in a later chapter. But it was preceded by similar theories. In 1492, for example, Metropolitan Zosima described Moscow as the ‘new Constantinople’. And a literary work known as the ‘Tale of the White Cowl’, probably dating from the early sixteenth century, describes how the white cowl of the Novgorod archbishops, symbolising the purity of Orthodoxy, was passed from Rome to Constantinople and thence to Novgorod after the patriarch had a prophetic dream of the fall of Byzantium to the infidel Turks.

The creation of an independent metropolitanate in Moscow had implications for Russia’s relations with Lithuania. Even after the metropolitan had moved from Kiev to Vladimir in 1299, he retained the title of ‘Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus’’. When the south-west lands began to come under the influence of the predominantly Catholic states of Poland and Lithuania, their rulers on several occasions persuaded the patriarch to create a separate metropolitanate for their newly acquired Orthodox population. The two sectors were reunited under Metropolitan Kiprian in 1390, but in 1458 King Casimir IV of Poland and Lithuania succeeded in obtaining the re-establishment of a metropolitanate based in Kiev: the new metropolitan represented the united Church created by the Council of Florence. Thereafter it became an aim of the Moscow-based metropolitans to re-unify the Orthodox populations of Muscovy and Lithuania not just under the same ecclesiastical authority, but also under the same political ruler. As Ivan III and Vasilii III expanded their realm westward into the Chernigov and Smolensk lands, there seemed to be a real prospect that Muscovy could re-unite the principalities of Kievan Rus’. After his annexation of Novgorod in 1478, Ivan III regularly used the title ‘sovereign of all Rus”, which echoed that of the metropolitan, and implied a territorial claim to the south-west lands which was of course contested by...