Chapter 1

“Time to Attend to the Wedding”

Origins and Traditions

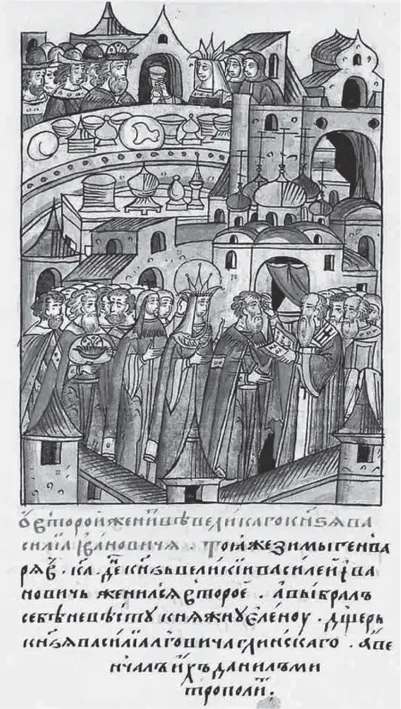

On January 21, 1526—a Sunday—Grand Prince Vasilii III sat in the Kremlin’s Wooden Dining Pavilion (Brusianaia izba stolovaia), dressed in royal regalia and surrounded by high-ranking courtiers, all of whom were also dressed in their finest court costumes. It was the grand prince’s wedding day, and the sequence of movements and rituals that made up a wedding in sixteenth-century Muscovy began, for him, there in the Dining Pavilion. Meanwhile, his bride-to-be, Princess Elena Vasil’evna Glinskaia, was in her apartment (v svoikh khoromekh) in the Terem Palace, where she had been residing since shortly after her selection in a bride-show. She, too, was dressed in her finest court costume and surrounded by the women of the court (boiaryni), many of whom were the wives of the men with the groom. At the appointed time, the grand prince sent instructions for the bride to go to the Middle Golden Palace (Sredniaia palata) and await his arrival. The Middle Golden Palace had been richly decorated for the occasion: tables were covered in rich linens and benches were positioned on both sides of the table with richly embroidered cushions topped by two forties of sable skins. When the bride and her retinue arrived, they all took their assigned seats, with the groom’s seat temporarily occupied by the bride’s younger sister, Anastasiia. Then Grand Prince Vasilii III’s brother, Prince Iurii Ivanovich, instructed a senior boyar (boiarin bol’shoi) to summon the groom. This boyar then went to the Dining Pavilion and uttered the prescribed words that set events in motion, words that hardly changed over the next century and a half: “Grand Prince! Sovereign! Prince Iurii Ivanovich orders me to say to you, beseeching God’s help: It is time to attend to the wedding.”1

Vasilii III was surely not the first to hear these words summoning him to his wedding. Royal grooms in previous generations had probably heard them too. But Vasilii III’s wedding was the first time they were ever recorded in a wedding ceremonial (svadebnyi chin)—the official document describing a royal wedding.2 Vasilii III’s and Elena Glinskaia’s ceremonial would serve as a model for later weddings up to 1624, when the first Romanov tsar married.3 Secretaries (d’iaki) in the grand-princely chancery—“ritual experts,” in Catherine Bell’s apt phrase—turned to it again and again as a reference source for how to arrange the wedding of a ruler: the “Tsar’s Happy Occasion” (Gosudareva radost’).4 The original ceremonial is today only a tattered fragment. It provides a description of events only on the first day of the wedding and part of the second, though we know the wedding was actually three days in length.5 Even so, few sources mark the beginning of a ritual tradition as well as this one.

Figure 1.1. The wedding of Vasilii III and Elena Glinskaia, in the Litsevoi letopisnyi svod. Wikimedia Commons.

Like the secretaries in the royal scriptorium, this chapter takes Vasilii III’s and Elena Glinskaia’s wedding as a starting point. It explores the origins, structural elements, and symbolism of the wedding ritual over the course of the sixteenth century. It compares Muscovite weddings with ancient Greek, Roman, and Byzantine weddings and explores the question of the origins of these rituals in the East Slavic space. The chapter also applies Arnold van Gennep’s model of rites of passage to Muscovite weddings and finds that these rituals—whether borrowed, homegrown, or some balance of the two—came to be firmly, organically tied to the underlying political culture. In fact, few court rituals were more responsive to, and expressive of, that political culture than weddings. When Muscovite secretaries and scribes developed a discrete set of documents to describe royal weddings at the turn of the sixteenth century, they created, perhaps unintentionally, a ritual template that lasted without much modification for more than a hundred years. This chapter describes and dissects that template.

Origins and Texts

That our first formal description of a Muscovite royal wedding ritual appears only in 1526 naturally prompts a number of basic questions: How were princely weddings performed before 1526—in Kyivan Rus’, in appanage Rus’, in early Muscovy? What were the essential rituals of a royal wedding? What were the various kinds of documents that secretaries, undersecretaries, and scribes created in the grand-princely chancery to help them choreograph royal weddings, and when did those documents first appear?

The question of when the royal wedding ritual took shape has stumped historians, ethnographers, and anthropologists for generations, as many have freely admitted. One can readily sense the frustration in perhaps the first important study of the wedding ritual, by D. I. Iazykov in 1834:

The domestic life of our ancestors is utterly inaccessible to us, and so we can hardly draw a very satisfying picture of it. Take, for example, wedding rituals, one of the most important features of the culture of all peoples, because in them is reflected an understanding of the public roles assigned to women: the typical representation of their position in society. Our chronicles and other documents are scant when it comes to descriptions of domestic life: one must search out and hunt for insights into that life in scattered documents, which contain only the flimsiest evidence from the recesses of antiquity and even down to the fifteenth century.6

A. I. Kozachenko, a Soviet scholar who in 1957 produced the first modern study of the Muscovite royal wedding ritual (and still one of the best), similarly lamented: “the history of the Great Russian wedding ritual has not yet been sorted out,” and “we do not know very much about the ancient Russian wedding ritual.”7 Daniel Kaiser agreed, admitting in his seminal article on Tsar Ivan IV’s weddings that “we do not know how most men and women of Muscovy celebrated their marriages.”8 In such discouraging circumstances, the best we can do is to go back to the sources we do have—chronicles, narrative tales, foreigners’ accounts, and, most importantly, the extant wedding-related documentation—to find the limits of what we can and cannot say about the origins and early history of the Muscovite royal wedding ritual.

The early sources are, indeed, spotty. Before 1526, we have only scattered glimpses of what the weddings of Rus’ian elites may have looked like and virtually no image at all of the weddings of nonelites. Rus’ian chronicles mention some of the elements of the wedding ritual, although they omit any narrative description of how a wedding was performed. For example, the dramatic account of the marriage proposal of Prince Mal of the Drevlianians to St. Ol’ga of Kyiv (d. 969) in the Rus’ Primary Chronicle (Povest’ vremennykh let) includes a number of allusions to wedding rituals. St. Ol’ga, the effective ruler of Rus’ from around 945 to around 963 and the first Christian convert in the Kyivan ruling dynasty, three times deceived the Drevlianians into handing themselves over to their own deaths.9 In the first story, twenty of the Drevlianians’ “best men” arrived by boat to ask for Ol’ga’s hand in marriage, having just murdered her husband, Prince Igor. Ol’ga had them wait in their boat while she secretly had a large hole dug in the ground outside the city. She then insisted the Drevlianians return to the city not by foot or by horse but carried aloft in their boat by the Rus’ in a procession. They were then cast into the giant hole and buried alive. In the second story, more Drevlianians arrived and were told to bathe before negotiating the marriage between Ol’ga and Mal but were burned alive in the baths. And in the third, Ol’ga traveled to the homeland of the Drevlianians herself and organized a sumptuous funeral feast for her slain husband, but after her Drevlianian hosts had all become drunk, she set her guards on them, killing everyone. Dmitrii Sergeevich Likhachev deconstructed the stories, pointing out how the emissaries from Prince Mal were like marriage go-betweens (svaty), and how the procession of the Drevlianian emissaries in their boat, carried aloft by the Rus’, mixed together ritual forms from both funeral and wedding processions.10 One might paddle farther down Likhachev’s stream of thought and find even more allusions to weddings—for example, in how Ol’ga’s request to have the second set of Drevlianian emissaries bathe before being burned to death and how the banquet in the third story doubled as a nuptial and a funerary event, baths and banquets being essential features of a wedding.

The Povest’ also mentions the unshoeing ritual (razuvan’e)—where the bride removes the shoes of the groom and prostrates herself before him as a sign of her submission—in the so-called “Legend of Rogned,” where the reluctant Rogned is asked if she is willing to marry Vladimir instead of his half-brother, Iaropolk, to whom she had been promised in marriage. Her famous reply may indeed be the earliest reference to the unshoeing ritual. When asked, “Do you want to marry Vladimir?” she replied “I do not want to unshoe a slave’s son, but I would unshoe Iaropolk” (ne khochiu rozuti robichicha, no Iaropolka khochiu).11 This line, plus references to the ritual in oral epic poetry (bylini) and other songs, has been taken by scholars as evidence that the unshoeing ritual was long a part of East Slavic wedding rites.12 This may be true, but this ritual is not recorded in royal wedding ceremonials, the Domostroi, or Kotoshikhin’s On Russia in the Reign of Aleksei Mikhailovich, although a colorful version of it can be found in Samuel Collins’s The present State of Russia.13

Another early case is the wedding in 1239 of St. Alexander Nevskii and the daughter of Prince Briachislav Vasil’kovich of Polotsk.14 The account reads: “Prince Alexander, the son of Iaroslav, married [ozhenilsia] in Novgorod, taking the daughter of Briachislav of Polotsk, and he married her [venchalsia] in Toropets, having there his porridge [tu kashu chini], and having it again [druguiu] in Novgorod.”15 Reference to the porridge no doubt signals it as the customary meal for newlyweds—grain being a recurring symbol of fertility and plenty—and “porridge” may also have served as a euphemism for the wedding banquet (pir) generally.16 Newlywed couples were similarly described as eating porridge in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in wedding ceremonials and in the Domostroi—on the second day of the wedding, right after taking (separately) their morning baths, although other wedding ceremonials report the meal was vegetables and wine.17

Finally, early wedding rituals appear in narrative sources and wedding songs. Terms that denote or derive from weddings appear in chronicles and tales, such as happy occasion (radost’ or veselie), wedding banquet, bride (nevesta), groom (zhenikh), and others.18 Scattered references in the late-twelfth-century (or late-eighteenth-century) epic Igor Tale, or Slovo o polku Igoreve, arguably evoke imagery and terminology derived from weddings: in the description of the loot taken from the Polovtsians on the first day of battle (lines 123–29), in the description of the climactic battle as a wedding banquet (lines 245–49), in the depiction of the bride at that banquet as a swan (lines 254–66), in Sviatoslav’s dream (lines 315–32), in Sviatoslav’s lament (lines 364–97), and elsewhere.19 Similarly, the evidence of wedding terminology and rituals in wedding songs (svadebnye pesni) is rich in insights and details about the emotional and performative aspects of weddings across the East Slavic spaces. The bride sings obligatorily (though probably very sincerely) a set of songs bemoaning her marriage, and the singing of songs (though not the lyrics) are recorded in the Domostroi.20 But there are serious lingering questions about the dating and provenance of both the Slovo and wedding songs. The twelfth-century origins of the Slovo remains for some very much an open question, although scholars on both sides of the debate concede the numerous allusions to weddings in the text.21 As for wedding songs, many cannot be reliably dated to before the eighteenth century, when they began to be collected, published, and, beginning in the 1920s, audio recorded.22

Western travelers who visited Muscovy—diplomats, merchants, and those whom Marshall Poe called “ethnographers”—frequently returned home to write accounts of what they saw and experienced.23 Their accounts are rich with details that often go unreported in Russian sources, mostly because the things that struck foreigners as noteworthy were often so unextraordinary to the Muscovites as to not merit special mention in their own accounts. While Poe found a “predilection for exaggeration” in their accounts, he nonetheless believ...