![]()

1

Spain and the Sixteenth-Century Corsairs

In the late fifteenth century, well before the rise of modern nation-states in northwestern Europe, the newly united kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were competing with the neighboring kingdom of Portugal for control over a burgeoning overseas trade. Both realms were more centralized than their northern neighbors, and better poised for expansion into the Atlantic than their competitors in the Mediterranean, mostly merchant interests based in the Italian city-states of Venice, Florence, and Genoa. The Portuguese and Spanish were initially interested in the spices and fine fabrics of Asia, then available only by way of Muslim middlemen, but they also sought to monopolize access to African gold, ivory, pepper, and, after 1441, slaves. Early sugar colonies were established on several East Atlantic islands, the Portuguese focusing on the Madeiras, Cape Verdes, and São Tomé, and the Spanish on the Canaries, or Fortunate Isles. Improved sailing technology made long-distance sea travel more feasible than ever before and in 1492 the Genoese Christopher Columbus sailed west across the Atlantic, or Ocean Sea as it was then called, thereby opening up a whole new world of possibilities for his Spanish sponsors. The Portuguese–Spanish rivalry now included the Americas, but the dispute was settled for the time being by a papal dispensation and the subsequent Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, effectively dividing the known world into halves, one for each realm. “The line” beyond which European peace treaties would often prove ineffective was placed at 370 leagues (c. 2,000 km) west of the Cape Verde Islands.

Other emerging European seafaring nations, along with virtually everyone else besides the Spanish and Portuguese, treated this division of the earth’s spoils as an act of contemptible arrogance. Thus, as the seaborne empires of Spain and Portugal developed in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, so too did the phenomenon of maritime predation, often in the form of piracy, or criminal sea raiding. The Spanish and Portuguese called the interlopers—some North African in origin, others French, English, or Irish—“corsairs” (corsarios), and quickly set about developing defensive measures to face them. Piracy had been a problem in the Mediterranean and North Atlantic for centuries, but the prey, prior to the windfall of American discovery and conquest, had been only moderately attractive. Now a regular sea traffic in gold, silver, gems, and sugar, compact and valuable items that nearly everyone wanted, was growing ripe for the picking.

The region of greatest risk for the Spanish, whose only connection to the wealth of the Americas was the transoceanic route opened by Columbus, was the so-called Atlantic Triangle, the East Atlantic Ocean bounded by the Iberian Peninsula and Moroccan coast of Africa, the Azores, Canary, and Madeira Islands. The threat to Spanish and Portuguese shipping in this region, mostly originating in France and the British Isles, but also the north coast of Africa, was real and immediately felt. Upon returning from his third voyage to the so-called New World in 1498, Columbus already feared French attackers near Madeira and took precautions to avoid an encounter. The multinational corsairs would in time spread beyond this region, entering American waters by the 1530s, just as the Spanish conquistadors were consolidating their control over the great interior empires of Mexico and Peru. But before the corsair threat reached the Caribbean Sea, the first American theater of pirate conflict, Spain faced other, more traditional enemies to its growing maritime empire in the Mediterranean. Indeed, since the problem of piracy in the Mediterranean drained Spanish wealth and military resources throughout the early modern period (c. 1450–1750), a brief consideration of this phenomenon will help to clarify Spain’s subsequent pirate policies in the Americas.

The Brothers Barbarossa and the Barbary Coast Corsairs

The famous voyage of Christopher Columbus coincided with another important event in Spanish history, the completion of the reconquista (ad 711–1492), or Christian Reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from descendants of early Muslim conquerors, or “Moors.” Much of Iberia had been in Christian hands for centuries, but it was only during the reign of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon that Granada, the last Islamic kingdom on the peninsula, fell. The conquest of Granada was completed in 1492, followed by the staggered expulsion of many Muslim and Jewish refugees, a diaspora that scattered these peoples throughout the Mediterranean basin and into various parts of Europe. The united kingdoms of Spain, under the so-called Reyes Católicos, or Catholic Monarchs, were vehemently intolerant of heterodox religious beliefs, particularly Islam and Judaism, and some factions even pressed for a counter-conquest, an extended crusade of sorts, against the Muslim and Jewish inhabitants of North Africa. Following the advice of one such militant, Francisco Cardinal Jiménez de Cisneros, Archbishop of Toledo, King Ferdinand began a program of conquest, focusing on the ports of the Maghrib, or Barbary (really “Berber”) Coast. Ferdinand’s campaigns between 1497 and 1510 led to the capture of the coastal settlements of Melilla, Mers el-Kebir, El Peñón de Vélez, Oran, Bougie, and Tripoli. Also in 1510, the Berbers surrendered control of an island off Algiers to the Christians, and the key fort of El Peñón (The Rock) was built upon it soon after. The Spanish were essentially following in the footsteps of the Portuguese, who had captured the key North African port of Ceuta in 1415.

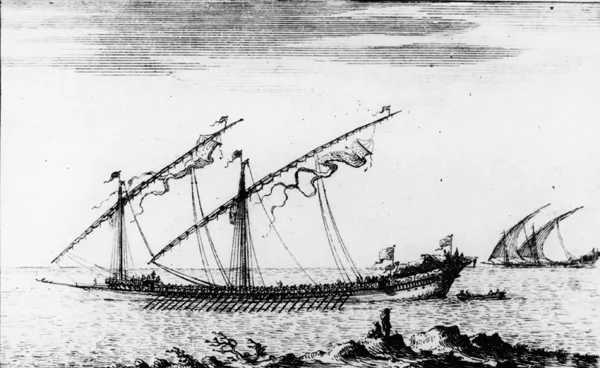

In addition to its Reconquest elements, the Spanish advance into North Africa was also in part a symbolic drive against the advances of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, which had stunned Christian Europe by taking Constantinople in 1453. The Ottomans backed the Berbers, and also the Iberian Muslim exiles who lived among them, and a sustained resistance to Spanish hegemony in the Mediterranean developed.1 The Barbary Coast might have been fully subjected to Spanish control, but the discovery of the Americas and coincidental political changes in Europe distracted from the purpose. Spain under the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1516–56), known in Spain as Carlos I, turned away from fighting Muslim pirates in favor of mainland European concerns, and with this shift in interest and resources the military outposts, or presidios, established by Ferdinand in the Maghrib became vulnerable. Resentment of the Spanish presence led Algerian Berbers to court the Ottomans, and an affiliate corsair by the name of Oruç, a native of the Greek island of Lesbos, took control of Algiers in 1516. Oruç had made a name for himself among the Ottomans as early as 1504 by capturing two richly laden papal galleys traveling from Genoa to Civita Vecchia, on the Italian coast near Rome, but he preferred to remain semi-independent of the Turkish sultan’s orders. Known to Europeans as Barbarossa (Italian for “Red-beard”), Oruç was followed in the pirate trade by his similarly red-bearded brother, Hayreddin, in 1518, and these Barbary corsairs, the Barbarossa brothers, soon became legendary figures.

Oruç had initially secured the sponsorship of the governor, or bey, of Tunis by offering him a tribute of twenty percent of any booty or ransom taken. Commission agreements allowed both parties some independence from one another, along with mutual gains, and would be followed by pirates and island governors in the Caribbean in the next century. The downside of such agreements, of course, was that the governors had little direct power over the corsairs. The consequences of this weakness could be taxing, as, for example, when Oruç became powerful enough that he lowered the bey’s tribute to ten percent of his take. Oruç Barbarossa continued to harry Christian, and particularly Spanish, shipping in the Mediterranean for about a decade, but his attempts to recapture the Spanish tributary cities of North Africa were unsuccessful. In a 1512 attempt on Bougie he lost an arm to an arquebus (or primitive matchlock) shot, and in 1518, two years after the death of King Ferdinand, he was killed by Spanish forces outside Tilimsan (Algeria). In spite of these failures, the first Barbarossa had proved a real menace to the Catholic kings. In what was perhaps Oruç’s greatest victory, a fleet carrying 7,000 veteran Spanish soldiers sent to relieve the fort of El Peñón in 1517 was all but annihilated by the one-armed corsair and his followers.2

FIGURE 1.1 An Early Modern Mediterranean Galley

The younger Barbarossa, Hayreddin, sought greater political legitimacy and firmer backing from the Ottoman sultan. He was named beylerbey, or regent-governor of Algiers, and already in 1519 Hayreddin was forced to defend his capital from an attack by a fleet of fifty Spanish warships under command of Hugo de Moncada. Barbarossa’s forces routed Moncada’s, and a number of similarly spectacular defeats of Christian armies and navies ensued. With the aid of Turkish reinforcements, including 2,000 of the famed janissary corps, the second Barbarossa finally drove the Spanish from their fortress at El Peñón in 1529. As a titled subject of the sultan, Hayreddin became more governor than pirate, leaving the business of sea raiding to a group of trusted captains, known as reis. Among the most prominent of these reis were Turgut (known to Europeans as Dragut), a Rhodes-born Muslim; Sinan, a Jewish pirate from Smyrna; and Aydin (or “Drub-devil”), a renegade Christian and possibly a Spaniard. The various reis and their crews rarely ventured into East Atlantic waters, the favorite haunt of French corsairs in this period, preferring instead to focus their efforts on Spain’s Mediterranean coast and the Balearic Islands. In 1529, the year of Hayreddin’s capture of El Peñón, Aydin Reis managed to rout a Spanish armadilla, or small fleet, of eight galleys off the island of Formentara. The armadilla’s commander, General Portundo, was killed in the fire-fight, and most of the surviving crewmembers were taken as slaves to Algiers. Perhaps anxious to share in the glories of the reis, the younger Barbarossa returned to the sea in 1534, now at the head of a fleet of sixty-one galleys. His principal objectives were in Italy, and included the capture of a famous young duchess named Julia Gonzaga, whom he hoped to seize at Fondi and offer as a present to the sultan. The duchess’s last-minute escape from the Berber corsair became a folktale in her own lifetime, and a disappointed Hayreddin was forced to turn his energies instead on Tunis, which he captured in a day.3

Spain continued a sporadic campaign against the likes of Hayreddin and his followers, sending the famous Genoese admiral Andrea Doria to recapture Tunis in 1535. A garrisoned fort, or presidio, was subsequently established at La Goletta, but diplomatic ties with local elites were weak and all of the Spanish presidios of North Africa were dangerously undermanned. A large fleet under Andrea Doria’s command was defeated by the Berbers off the distant Albanian coast in 1538, and a new attempt on Algiers in 1541 failed miserably, though more as a result of storms than of organized resistance. Among the many notable participants in the battle of Algiers was Hernán Cortés, the famed conquistador of Mexico, then in Spain fighting to maintain title to his American holdings. The equally famous Barbarossa the younger went on to form an ambiguous alliance with Francis I (1515–47), Spain’s enemy and king of France, before his death in 1546. The Ottomans did not neglect their promises to the Berbers after the death of the Hayreddin, and in 1551 they sent Turgut Reis (Dragut) to recapture Tripoli from the Knights of Malta. The knights had been established in Tripoli since 1530, dispatched by Charles V, but they proved to be no match for Dragut and his seasoned corsairs.4

No individual pirates rose to the legendary status of the Barbarossa brothers after the mid-sixteenth century, but Barbary Coast piracy was by no means dead. Forced Muslim converts to Christianity in Spain, known as moriscos, were unhappy with a variety of discriminatory measures used against them, and many rebelled in 1569. The governor of Algiers, Uluç Ali Pasa, took advantage of the distracting Morisco uprising in Spain to recapture Tunis. Things could still go both ways, however, as Don Juan of Austria, a young admiral fresh from a resounding victory over the Ottoman naval forces at Lepanto in 1571, managed to retake Tunis for the Christians in 1573. It was a hollow victory, however, as Uluç Ali Pasa soon recaptured the city, along with the important Spanish presidio of La Goletta, in 1574. Thus the fight for the North African coast in the sixteenth century resembled a tug-of-war, with neither side victorious. The disastrous defeat at Lepanto, however, led the Ottomans to seek a peace with the Christians, and an agreement signed in 1580 lessened the importance of the Maghrib as a theater of Turkish–European conflict. What the region became instead was a pirate nursery, a permanent home for corsairs and disgruntled Muslim-Jewish exiles, and a constant thorn in Spain’s side.

Berber piracy after the Battle of Lepanto and resulting treaties was a kind of guerrilla, or “little war,” with mostly Muslim corsairs preying on Spanish and other European shipping in the Mediterranean until the 1810s, when this activity was finally suppressed by allied forces and the fledgling U.S. Navy. Robbery was certainly an important feature of Berber piracy, but more often it consisted of rescate, or bargaining to ransom captives based on their wealth and status. (Rescate in the Caribbean and other American contexts, as will be seen, referred to the practice of contraband trading, or forcibly breaking Spain’s monopoly arrangements with its colonies. Portuguese resgate was somewhere in between the Mediterranean and American forms, usually referring to the “ransoming” of sub-Saharan African captives, a cover for slave trading.) The ransoming of Christian captives, most of them Spaniards, from the bagnios, or jails, of Algiers and other cities of the Muslim Maghrib became highly formalized in the sixteenth century. This form of rescate involved many notable personages, including Spain’s most famous writer of fiction, Miguel de Cervantes. Cervantes, a veteran of the Battle of Lepanto, was taken hostage by Berber corsairs in 1575, and he seems to have drawn on his personal experiences in describing the captive’s life in the following passage from Don Quixote (1614):

So I passed my life, shut up in a prison-house, called by the Turks a bagnio, where they keep their Christian prisoners: those belonging to the King and those belonging to private people, and also those who are called the slaves of the Almazen—that is to say, of the township—who are employed in the public works of the city and in other ...