![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Mediterranean Slavery

Before he became a sea rover, ‘Ar

j was a slave. The son of a onetime Turkish soldier and the grandson of a Greek Orthodox priest, by the early sixteenth century he had made a name for himself as a Muslim corsair captain, or

ra’is, attacking Christian shipping from his base off the Tunisian coast. As his reputation for looting cargo and snaring captives grew, the inhabitants of Algiers recruited him to help expel their Spanish occupiers. Killed in battle in 1518, ‘Ar

j did not live long enough to see the territory become an Ottoman dependency in 1529 with his brother installed as its first pasha. But his brother, Kheir al-Din, later known as Barbarossa or Redbeard, continued the family legacy of conquest, briefly taking Tunis in 1534 before it fell to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V the following year.

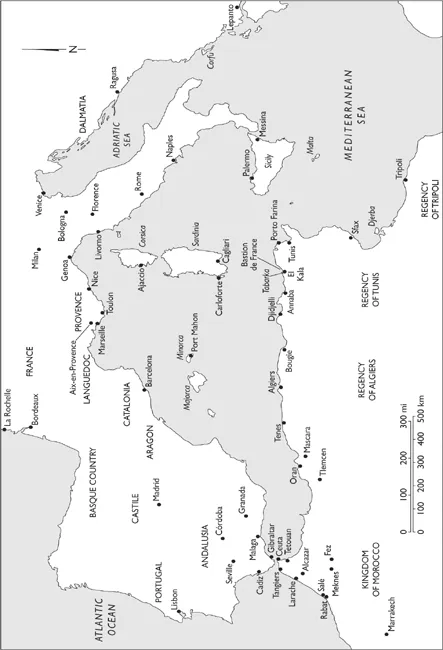

1 When the long struggle over control of North Africa finally abated in the 1580s, Morocco had won complete autonomy and Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli had emerged as reluctant “regencies” of the Sublime Porte in Constantinople (Figure 1).

2From these turbulent beginnings and mixed ancestries, the Barbary States developed into polities dependent on maritime plunder, whose reputation as “pirate republics” struck terror in the hearts of Europeans until the nineteenth century.3 Even though Christian powers sponsored their own corsairs in the form of military orders like the Knights of Malta and Livorno—in addition to licensing private captains to steal Muslim merchandise and men—they tended to portray Mediterranean seizure and enslavement as a one-sided affair.4 In fact, thousands of Ottomans and Moroccan rowers (sometimes Jewish or Orthodox yet indiscriminately known as “Turks” or “Moors”) were captured and sold by various European powers5 for service aboard Maltese,6 Italian,7 Spanish,8 and French9 galleys. Meanwhile, their compatriots of diverse geographic origin ravaged coasts and coves from Palermo to Valencia. These Berbers, Arabs, and Jews of various provenance; Muslim exiles from Iberia; and Christians who converted to become “Turks by profession”10 carried off lone shepherds, entire villages, and boats of all shapes and sizes, turning even more Catholics (and some Protestants) into slaves.11

Figure 1. Map of the early modern Mediterranean.

In 1530 and 1531, as Hungary surrendered to Ottoman advances, communities along the southernmost tip of France suffered incursions too.12 Yet compared to their neighbors French subjects had relatively little to fear during the first half of the sixteenth century, because of an informal alliance between King Francis I and Sultan Suleiman I.13 For the most part, rather than attack France’s ships and shores, corsairs from North Africa brought military protection against the Habsburgs; for six months between 1543 and 1544, thirty thousand members of the Ottoman fleet wintered in Toulon.14 Even a decade later, at least from a royal perspective, the presence of “Barbary pirates” on the Inner Sea remained more an annoyance to be handled diplomatically than a serious threat. In the 1550s, for example, ambassadors began forwarding occasional grievances to the Porte about raids, or razzias, on Provence and Languedoc.15 A “maritime and limitrophe city” with long-standing ties to North Africa and relatively recent ones to France, Marseille (annexed in 1486) took separate measures to protect commerce and liberate natives, even as it petitioned regent Catherine de Medici about the seizure of vessels.16 Nevertheless, in the five years prior to 1565, when Suleiman I formally ordered North African brigands away from French targets, Marseille had lost “ten or twelve nefs [large galleons]” and a “large number of boats.”17 It was partly to “keep an eye on these corsairs” that King Charles IX established the first consular outposts in North Africa and staffed them with Marseillais.18

Still, at a time when reports had it “raining Christians in Algiers,” the number of French ones carried into captivity was bound to surge.19 Expressing a widely shared conviction about the propensity of southern Europeans to “apostasy” (conversion to Islam)20 and the propensity of neophyte Muslims to piracy and pederasty, court cosmographer Nicolas de Nicolay wrote in 1568 of the “renegade or Mahumatized Christians” from Spain, Italy, and Provence “all given to smut, sodomy, theft, and all the most detestable vices . . . [who] with their piratical art bring daily to Algiers an incredible number of poor Christians, whom they sell to the Moors and other Barbary merchants as slaves.”21

Yet thanks to the Capitulations (ahdnames)—depicted as a bilateral agreement by the French but understood as a one-sided bequest by the Ottomans—officially signed in 1569, those claimed by France were not exposed to such alleged religious and sexual deviance for long.22 A year after the Holy League’s 1571 victory over the Ottoman Empire at Lepanto,23 at the climax of France’s Catholic-Calvinist Wars of Religion,24 all five hundred Frenchmen in Algerian thralldom seem to have gone home.25

FRANCE’S FREE SOIL

The wholesale liberation of French subjects also coincided with the most cited articulation of a free soil principle for France. “France, mother of liberty, allows no slaves,” the Parlement of Guyenne reportedly ruled after a Norman merchant attempted to sell several “Moors” he had purchased on the Barbary Coast.26 Thereafter, illegally subjugated Turks prized for their strength at the oar notwithstanding, Muslims unbound became as central to political theories of freedom as captive Christians already were to everyday understandings of slavery.27 With the demise of serfdom between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, a primary reference for conceiving personal status in France was the Mediterranean Sea, whose waves carried some to doom and others to deliverance. It would be another fifty years before French colonizers put down roots in the Caribbean and fifty more before French traders did more than pick occasional sub-Saharan Africans off the continent’s Atlantic shores or steal them from Iberian and Dutch competitors. From a late sixteenth-century French vantage, the archetypal slave was either a Muslim abducted to Europe or a Christian abducted to North Africa.

In common usage, captif (from the Latin captivus) and esclave (from the medieval Latin sclavus, by way of the Byzantine Greek sklabos for Slav) were synonyms without modern racial or temporal distinctions. Heirs to conflicting classical views on the origins of human bondage, French subjects across the social spectrum generally ascribed the condition not to nature but to misfortune, even as they framed it as the outcome of an ongoing—if in their case theoretically suspended—clash between Crescent and Cross.28 Though anxious that French corsair victims not switch religion or perish from disease, those most familiar with captivité, esclavage, servitude, and esclavitude assumed the possibility of a happy endpoint, based on a monotheistic tradition of redemption.29 The French were attuned to physical difference and even inclined against blackness, but they did not yet categorically distinguish servitude by skin color.30 What contemporary scholars have begun to term “ransom slavery,” or captivité de rachat, whose fluidity reflected its watery genesis, was spatially conceived and spiritually inflected.31 It was dependent on the reciprocal exploitation of multiethnic “infidels,” not racial “others,” and replenished via acquisition rather than reproduction. Its influence endured in metropolitan France for almost two more centuries.32

SLAVERY AND STATE BUILDING

As an abstraction, Christian slaves in Muslim lands—given different literal and euphemistic appellations across North Africa—helped confirm the nature of French territoriality.33 As an increasingly concrete reality, Christian slaves in Muslim lands spurred action from municipalities and—when not distracted by more pressing affairs—from monarchs. By 1585, for example, Marseille’s commercial livelihood stood in sufficient jeopardy that the city organized an offensive league of Provençal ports to fight the Barbary corsairs. Concerned the following April about the bodily integrity and religious and political loyalties of vulnerable subjects, King Henry III had his ambassador in Constantinople protest the actions of five Algerian galleys that “took two French saettias [vessels with lateen sails] from Marseille and ransacked everything, killing the men and forcibly converting and circumcising a young boy,” and wrote directly to the pasha and to the sultan about depredations by Tunis and Tripoli.34

Yet royal intercession on behalf of the kingdom’s gateway to the Mediterranean stopped soon enough. When Marseille joined the secessionist Catholic League during the Wars of Religion, heir to the throne Henry of Navarre recognized the potential alongside the perils of North African corsairing; in 1590 he used his good offices with Sultan Murad III not to end physical captivity but to promote political vassalage. “We enjoin you to yield to your leaders and render obedience to that most magnanimous among the great and powerful lords,” read the letter sent by the Ottoman sovereign to the city. “If you persist in your sinister obstinacy,” it continued, “we declare that your vessels and their cargoes will be confiscated and your men made slaves.”35 The rebellious city decided to dispatch an emissary of its own to Algiers.36

Six years later Marseille resumed allegiance to the king. But by then the three Barbary regencies, chafing against authority from Constantinople, were pursuing ever more independent foreign policies,37 making it increasingly difficult for sultans to enforce their security pledges to France.38 Though French ambassadors inundated Ottoman authorit...