1

A Tale of Two Despots

The Invasion of Algeria and the Revolution of 1830

ALMOST ANY ACCOUNT of the French conquest of Algeria begins with the July Revolution of 1830. According to historians of both French politics and North African colonialism, the invasion of the then–Ottoman regency was a by-product of the Bourbon Restoration’s final collapse. Faced with widespread popular opposition and a strong liberal majority in the elected Chamber of Deputies, King Charles X and his ultraroyalist prime minister, Jules de Polignac, engineered the expedition against Algiers in a last, desperate bid for public and electoral support. To no avail. Barely three weeks after the fall of Algiers on 5 July 1830, a revolutionary coalition of liberal deputies, journalists, artisans, and workers took to the streets of Paris. When the smoke cleared at the end of the “Three Glorious Days” of 27, 28, and 29 July, Charles had abdicated, and his cousin, Louis-Philippe d’Orléans, had assumed the throne as “King of the French.”

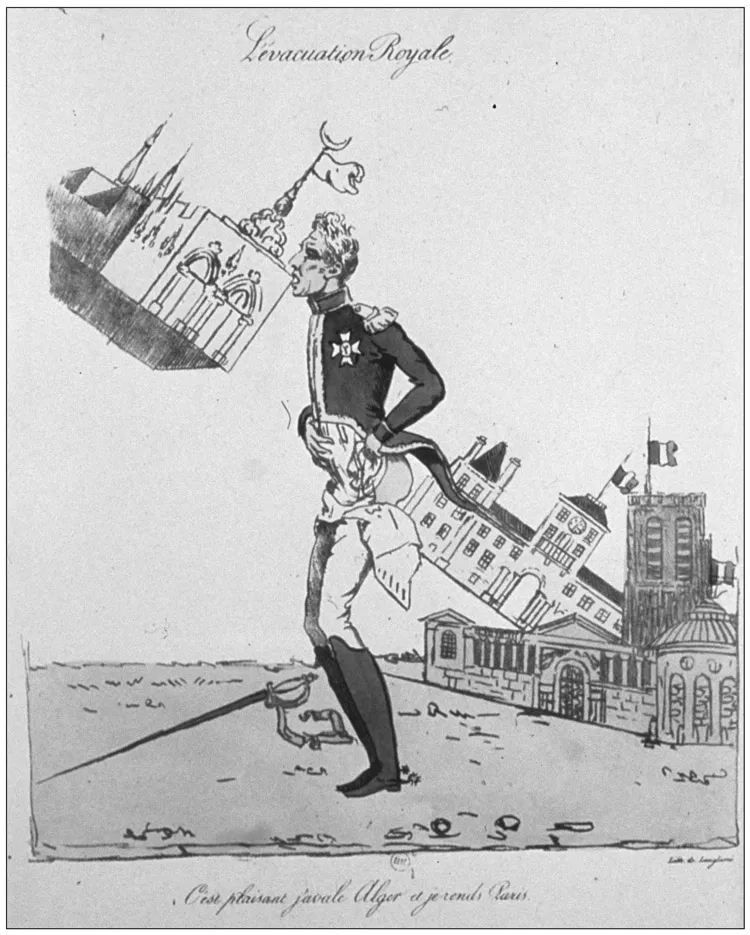

This turn of events, which so quickly transformed the conqueror into the conquered, delighted the monarchy’s many opponents. Satirists unleashed a gleeful torrent of caricatures like The Royal Evacuation, by the Parisian lithographer Langlumé (fig. 1).1 Printed less than a week after the revolution, The Royal Evacuation made crude fun of the brief interval separating the fall of Algiers from the fall of Paris. The cartoon depicts Charles X straining to swallow a generically “Oriental” building, identified by the caption as the city of Algiers, while his backside extrudes a Parisian-style edifice that falls to join the silhouette of Notre Dame cathedral on the ground behind him. The caption, in which Charles exclaims, “How funny! I swallow Algiers and I give up Paris,” mocks the king’s political naïveté in expecting to rally popular support with military victory in North Africa.

Much of the humor of Langlumé’s cartoon derived from its scatological play on the timing of the two capitals’ respective falls. But it also carried a more serious message about the links between the Algiers expedition and the July Revolution, which became one of the most popular themes in revolutionary political satire in 1830.2 By linking the two events through the body of the king, Langlumé gave visual expression to the entanglement of the Algerian invasion in the politics of monarchy in postrevolutionary France. Invoking Rabelais’ gluttonous Gargantua, the print satirized Charles X’s unmeasured appetite for power and its fatal consequences for the legitimacy of royal authority. More subtly, the identifying features of the two cities reference the confrontation between sacred and secular authority that defined the political culture of the late Restoration. The minarets of the Algiers skyline and the towers of Notre Dame stand in silent contrast to the tricolor flags and civic architecture of the unidentified Parisian building. Coarse as it is, The Royal Evacuation encapsulates the ways that the invasion of the Ottoman regency, justified by Charles X and the Polignac ministry as a righteous attack on religious fanaticism and despotic rule, articulated the competing political ideals at stake in the Revolution of 1830.

The popularity of such satires reflects the fact that there was more to the relationship between the July Revolution and the Algiers expedition than a simple campaign stratagem. The monarchy did, as we will see, intend the expedition to divert public attention from domestic travails, including a worsening economic recession, a wave of mysterious fires in Normandy, and the growing unpopularity of the Polignac government. In this respect, the Journal des débats newspaper was correct to describe the invasion as the work of “ministers without a majority in the Chambers or the electoral colleges who simplemindedly think they can escape their fate with smoke and noise!”3 But the specific forms of that smoke and noise had a deeper political significance, as well. Closer investigation of the ways that the government and its opponents represented the expedition shows not only why it failed to salvage the monarchy, but how it actually served to further undermine the legitimacy of the Bourbon regime. Charles X and his supporters publicly portrayed the invasion as an expression of their ultraroyalist conception of Christian kingship, but simultaneously justified it by invoking the values of secular liberalism. Royalists claimed to act in the name of liberty and reason against political despotism and religious fanaticism, even as they celebrated the expedition as an act of divinely inspired royal power. Caricatures like The Royal Evacuation encapsulated this contradiction and, in this regard, embody both the roots of the Algerian conquest in the conflicted political culture of the Bourbon Restoration and the role of the expedition in precipitating the crisis of legitimacy that brought it down.

FIGURE 1. The Royal Evacuation, lith. Langlumé (Paris), 1830. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Estampes et de la photographie.

The Political Origins of the Algiers Expedition

Accomplished in just three days, the July Revolution of 1830 lacked the bloody drama and radical outcomes of the other nineteenth-century French revolutions. The men of 1830 did not proclaim a republic and institute universal (male) suffrage. Instead, they installed Charles’s cousin, Louis-Philippe, as “King of the French” under a constitutional Charter little different from the one it replaced. Property qualifications for the suffrage were extended only minimally, and voting remained the privilege of a small group of wealthy notables. The Revolution of 1830 thus constituted less a struggle between republicanism and monarchy than a crisis of legitimacy within the system of constitutional monarchy instituted after the fall of Napoleon. Because of its apparent moderation, 1830 remains the least-studied of all the French revolutions.4 Yet it was this crisis that provided both the immediate trigger and the symbolic framework for the invasion of Algiers. Viewed from an imperial perspective, the July Revolution stands as one of the most significant events in modern French history.

The political culture of the Bourbon Restoration was characterized from the outset by “a continuous public and participatory negotiation over the nature of legitimate authority.”5 Conservative ultraroyalists saw the return of the Bourbons in 1814 as an opportunity to revive the sacred kingship of the Old Regime. Liberals, by contrast, interpreted the restored monarchy as a constitutional regime based on the secular principles of popular sovereignty, the rule of law, and parliamentary governance. These contradictions were embodied in the constitutional Charter of 1814. Issued in the name of “Louis, by the grace of God, King of France and Navarre,” as a gift rather than an obligation to his subjects, the Charter vested sovereignty in a sacred, inviolable royal person and reestablished Catholicism as the state religion. Yet it also maintained certain revolutionary rights and institutions, including equality before the law, freedom of expression and of religion, and a Chamber of Deputies elected by some ninety thousand of the kingdom’s wealthiest taxpayers.6 Ultraroyalists read the regime’s founding document as reconstituting the absolute monarchy of the Old Regime, while liberals construed it as a contract between monarch and nation that subjected the king to the will of the people. The restored Bourbon kings were thus caught between two incompatible views of sovereignty and royal legitimacy.

Contradictions between sacred and secular royal authority pervaded the ceremonial and parliamentary politics of the Restoration, especially after the accession of Charles X in 1824.7 Under Louis XVIII (r. 1814–24), a policy of oubli, or compulsory forgetting, aimed to simply ignore divisive revolutionary memories. His devout brother, however, sought to reinstate the symbolic foundations of the Old Regime monarchy. Royal rituals, from Charles X’s elaborate coronation in May 1825 to the papal jubilee of 1826, proclaimed the king’s divine authority and identified the regime with the Church in both elite and popular political discourse. Restoration liberals, on the other hand, were united by a resolute anticlericalism and what they saw as the political principles of 1789: popular sovereignty, patriotism, and the rule of law.8 A loose coalition of moderate constitutionalists, republicans, and Bonapartists, they saw efforts to “resacralize” the monarchy as a plot led by counterrevolutionary priests to resurrect the clerical, aristocratic, and royal privileges of the Old Regime. Seditious placards, songs, caricatures, defaced coins, even baked goods portrayed Charles as a Jesuit or a bishop, and spread rumors of a clerical conspiracy through French society.9

A series of laws indemnifying aristocrats for property confiscated during the Revolution, reauthorizing female religious communities, and making sacrilege a capital offense aggravated electors’ disquiet about the reactionary turn of the “Jesuit-king,” and liberals gained a majority in the Chamber of Deputies from 1827, escalating the struggle between conceptions of monarchy into a full-blown constitutional crisis. The appointment in August 1829 of the extreme ultra Polignac government brought matters to a head over the question of ministerial responsibility.10 Polignac’s views were diametrically opposed to those of the liberal majority, and his nomination seemed to confirm liberals’ fears of a plot to “return [our country] to the yoke of ultramontane fanaticism and absolute power.”11 Liberal deputies, writers, and caricaturists responded with a deafening chorus of outrage about the new ministry and began to predict a royalist coup d’état against the Charter. Ultras, who believed the appointment of ministers was an unfettered royal prerogative, saw in the storm of protest the seeds of revolution. They called on the king to invoke Article 14 of the Charter, suspending the Chambers and asserting dictatorial powers in the name of “state security.”12

At the opening of the 1830 parliamentary session, Charles X concluded his annual address with a ringing assertion of the sacred nature of royal power and, in a thinly veiled reference to Article 14, of his duty “to maintain the public peace” in case of “criminal maneuvers” against the government.13 Liberals responded with a statement, signed by 221 deputies and presented to the king on 18 March, that the Polignac ministry posed a direct threat to the Charter and to public liberty.14 The next day, the king prorogued the session, raising expectations that the Chamber would be dissolved at an opportune moment. That moment came on 17 May, as an invasion force of thirty-seven thousand prepared to sail from Toulon to Algiers. By the time the fleet left port on 25 May, campaigning was well underway for elections now set for late June and early July.

Officially, the French expedition against Algiers was a punitive one. The Algerian merchant house of Bacri had supplied grain to the French army during the Directory, payment for which had never been entirely settled.15 In April of 1827, during a discussion of the Algerians’ demands for reimbursement, Hussein, the dey (governor) of Ottoman Algiers, struck the French consul with a fly swatter. The French responded to this “outrage” by declaring war and instituting a naval blockade of the regency.16 Two years later, a French parley ship was fired upon in Algiers harbor after the commander of the blockade squadron met with the dey to propose an armistice. Polignac, then minister of foreign affairs, rejected Hussein’s apologies and, instead, proposed an invasion of the regency. Charles X approved this plan in October 1829, just two months after Polignac’s installation as president of the Council of Ministers. Initial...