![]()

Part I

Michael Chekhov in Context

Theory, practice, pedagogy

![]()

1

Michael Chekhov’s work as director

Liisa Byckling

Michael Chekhov was a modern director of the type established in the second half of the nineteenth century. For thirty years he combined directing with actor training in many theatres and studios, and with literary work: writing scenarios in close collaboration with playwrights, who became members of his team; producing articles; and authoring one of the best autobiographies of a Russian actor.1 “One of the most remarkable actors of our time, Michael Chekhov, ardently and passionately seeks new means of theatrical expression,” wrote Pavel Markov, a distinguished Moscow critic (Chekhov 1986: 2.492). As director of the Second Moscow Art Theatre (MAT 2) from 1924 to 1928, Chekhov sought to implement a new means of acting in his productions. He was guided by several creative principles: acting as collective work; a preference for classical repertoire as his dramatic choices; the use of adaptation techniques in creating scores of performances; and creating an ensemble of actors. His focus on actor pedagogy as the basis of directorial work went back to his teacher Stanislavsky’s tradition in directing. Chekhov’s great artistic pilgrimage stretched from Moscow to Los Angeles.2 After leaving Russia he underwent three separate stages in his development: the period of directing, acting, and teaching in Berlin, Paris, Riga, and Kaunas (1928–34); the period of the Anglo-American Theatre Studio and professional theatre (1936–42); and, finally, acting in cinema, writing books, and teaching film actors in Los Angeles (1943–55). Being an émigré, he was often obliged to work with heterogeneous groups and in uncongenial cultural contexts; nevertheless, he always found sponsors and admirers of his talent.

Director in Moscow

Edward Braun defines the fundamental requirement of theatre production as “the coordination of expressive means based on an interpretation of the play-text” (1982: 7). In Russia the role of the director was consolidated in the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT), founded in 1898 by Konstantin Stanislavsky and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko. Following the practice of his teachers, the directors of the MAT, Chekhov had a twofold professional function: first, he had overall responsibility for the rehearsal of any play that reached the stage in his theatre; and, second, as head of the MAT 2 he was responsible for the artistic and ideological work of one of the leading Soviet Russian theatres of the 1920s. Like Stanislavsky, Chekhov studied theatre art and gained his knowledge of it from the standpoint of the actor and not that of the director. The actor, his or her technique and personality, was always paramount for Chekhov.

Chekhov’s individuality as an actor was determined by the social situation and aesthetic values prevalent at that historical point. He belonged to the generation of the 1910s, so that his formative years coincided with a period of swift social change, marked by the 1905 and 1917 revolutions in Russia. It was a period of symbolism in art and modernism in literature. In the theatre there was the generation of “post-Stanislavskian” actors and directors, who were searching for alternatives to psychological realism. Chekhov’s favorite writer was Dostoyevsky; one of his spiritual fathers was the symbolist writer Andrey Bely; and his sources of inspiration came from religious philosophy. Like Edward Gordon Craig, one of the first great theorists of the director’s theatre, in Russia Chekhov developed his theory of the Theatre of the Future, fulfilling a twofold function as actor-director and actor-philosopher.

Chekhov acknowledged his indebtedness to Stanislavsky’s pioneering achievements in theatre. In his Hollywood lectures (1955) he declared: “Others are said to have surpassed and even bypassed him, but he, together with Nemirovich-Danchenko, was the first to break the land that opened up the new fields which all of us later tilled in our own distinctive ways” (1963: 39). Comparing the two MAT directors, he wrote about their collaborative productions of his uncle Anton Chekhov’s plays: “From the brilliant mathematician [Nemirovich-Danchenko] came the skeleton of the play, from the great humanist [Stanislavsky] came the real-life moods and atmospheres3 to flesh it out” (ibid.). Chekhov developed creatively the special qualities of the MAT productions that he saw and was influenced by. At the rehearsals of Nikolay Gogol’s The Government Inspector (1921), Stanislavsky the director and Chekhov as Khlestakov inspired each other. Challenged by his teacher to perform Khlestakov in a grotesque manner, as “a symbol of emptiness and evil, an embodiment of that very ‘void’ Gogol identified with Devil” (Slonim 1963: 273), Chekhov had tremendous success in the role. His acting stunned the audience with its unbelievable ease of improvisation and unrestrained imagination (Stroyeva 1977: 60; Rudnitsky 1988: 52). Many years later, Chekhov would refer to Stanislavsky’s book An Actor Prepares (1936), calling the suggestion for tackling the part – the analysis of “units and objectives” – one of Stanislavsky’s most brilliant inventions:

[…] when properly understood and correctly used they can lead the actor immediately to the very core of the play and the part, revealing to him the construction and giving him a firm ground upon which to perform his character with confidence.

(1953: 154)

In his creative work with actors, Chekhov would go on to employ Stanislavsky’s method: finding the subtext, the through-line of action, and the superobjective (Byckling 2013: 70–71).

Chekhov’s directorial work was strongly influenced by the Russian avant-garde theatre of the 1920s. In the First Studio, founded in 1912 and led by Stanislavsky and Sulerzhitsky, the productions of the brilliant director Yevgeny Vakhtangov (1883–1922) shaped his concept of the theatre. Vakhtangov believed that the theatre must create imaginary forms; he called this “fantastic realism.” Chekhov wrote that he “leaned in Vakhtangov’s direction,” in the way he moved from naturalism to stylization and then was infected with theatricality (1986: 1.183). In 1921 Chekhov created the memorable role of the tortured monarch in August Strindberg’s historical drama Erik XIV directed by Vakhtangov. He and Chekhov brought nervousness, morbidity, and acuity to the art of the Studio (Rudnitsky 1988: 21).

Chekhov learned expressive means and rehearsal methods from Vakhtangov, both based on a mutual trust between director and actor. Vakhtangov had “a special feeling for the actor” (Chekhov 2005: 68) and used a special working language: “[Actors] must learn to embody their thoughts and feelings in images and exchange them with one another, thus replacing long, boring and pointlessly clever conversations about the play […]” (70). They shared an interest in the commedia dell’arte, myth, and folklore. Chekhov learned from Vakhtangov the need to educate actors in the rhythmic expressiveness and plasticity of the body. Vakhtangov’s work as a director was probably the source of the almost nonverbal international theatre that Chekhov attempted to create in Paris. Moreover, Chekhov also acquired from Vakhtangov his understanding of the role of the spectator as a third component in theatre (Chekhov 1953: 162).

The leading Russian and Soviet director Vsevolod Meyerhold (1874–1940) and Chekhov were drawn to each other by mutual admiration. Meyerhold spoke with enthusiasm about Chekhov’s Khlestakov as the grotesque essence of Gogol’s comedy (Chekhov 1986: 2.446). When Meyerhold’s 1926 staging of The Government Inspector aroused heated discussion, Chekhov was one of his eager defendants in the press and public discussions. He considered Meyerhold’s bold and talented break from tradition as the ideal approach to classics (2.99). Meyerhold’s way of reconstructing dramatic texts and his powerful expressive techniques influenced Chekhov. In his publications he saw both Stanislavsky and Meyerhold as leading figures in the future of Russian theatre.4

Chekhov’s “spiritual theatre”

After the Russian revolution of 1917 a new orientation took place in Chekhov’s philosophy of life and theatre. He combined elements of Stanislavsky’s system of acting, Vakhtangov’s Fantastic Realism, and German philosopher Rudolf Steiner’s spiritualism to create his own method. Chekhov’s experimental studio (1918–21) laid the basis for his subsequent studios. The only public performances he directed at the studio, Leo Tolstoy’s The First Distiller and Nikolay Popov’s Shemyakin’s Justice, were in the folklore tradition. After Vakhtangov’s death in 1922, Chekhov became director of the First Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre, which was renamed the Second Moscow Art Theatre (MAT 2) in 1924. As artistic director, he aimed at creating a theatre as an artistic unit with its own style and “ideology” of spirituality and anti-materialism.5 Chekhov sought to withstand the threat of ideological tendencies that had led the Studio away from the spiritual values established by its founders: “First and foremost I prohibited anti-religious tendencies and the theatre of the streets and decided to stage Hamlet as a counterbalance” (1986: 1.203). Hamlet and the second important production Petersburg staged at the MAT 2 by Chekhov were meant to be defining landmarks of his spiritual theatre and demonstrate the mastering of new methods of acting (Byckling 2006: 58–71). “With each new production we had the opportunity of studying and developing new methods of acting and directing” (Chekhov 2005: 135).

Being dissatisfied with modern Soviet drama, Chekhov proposed “heroism and humor” as the two desirable theatrical styles. To avoid narrow, psychological interpretations of the classics, as well as to reform the art of acting through the use of archetypes, gesture, and rhythm, Chekhov turned to myths and folk-tales, which he recommended for their “healthy dynamism, real poetry and acute wisdom” (1986: 1.99–101). He also suggested a new way of writing and reading texts. Following the MAT method of directing Anton Chekhov’s plays by translating the “subtext” into a scenic score, Chekhov compiled texts, which actors had to interpret on the deepest level. His first attempt at writing a drama, an adaptation of Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote, had both philosophical and artistic aims.6 It was a playscript, not a conventional drama. He wrote: “Future plays will probably be difficult to read, they are good only for acting” (2.113). Consequently, director and actors were accorded equal status with the playwright.

Russian theatre historians have long denied that Chekhov possessed any great directorial talent. He was believed to have relied on collective direction as practiced from the very start at the MAT by its founders: at the MAT 2 he would create a group of directors to work on each play (Rudnitsky 1988: 113). Deservedly, however, Chekhov has been rehabilitated as a director in recent Russian research. In the new history of the MAT 2 Svetlana Kurach writes that, while Chekhov chose not to publish his name in the posters for Hamlet and Petersburg, he was the actual director of the performances, aided by assistants. Moreover, in the 1920s Chekhov’s authority was indisputable, and his theatrical method was taking definite forms (Kurach 2010: 90). Even after his emigration, his colleague Aleksandr Cheban spoke about the useful lessons Chekhov had taught young directors in rehearsal methods and play analysis (2011: 368–9).

Chekhov’s new method of rehearsing was developed while working on the experimental production of Hamlet. He regarded the play as a type of spiritual theatre, the meaning of which lies outside the text. Since 1918 the writings of the German anthroposophist Rudolf Steiner had exerted a powerful influence upon Chekhov. For him anthroposophy was a new movement directed towards the unification of science, art, and spiritual knowledge. Anthroposophy became his private religion, a modern form of Christianity. In his approach to speech and movement, Chekhov adopted Steiner’s method of eurythmy, according to which every sound has an inherent gesture, which may be reproduced in movements of the human body. The actors of the MAT 2 became involved in his experimentation. Chekhov had found an approach to the word and expressiveness of movement that corresponded to his own way of acting and to the principles of Vakhtangov’s theatricality; however, his Russian symbolist philosophy of art often prevailed in rehearsals at the expense of scenic form and a unified style of performance.

Bely’s Petersburg

The next stage in Chekhov’s experimentation was his work on Andrey Bely’s novel Petersburg (1925). Bely (1880–1934) was a prominent Russian symbolist writer and a leading member of the Russian Anthroposophical Society. A friend of Chekhov’s, Bely admired his acting and views on modern culture, and became involved in the studio and the rehearsals. Bely’s Petersburg, which is considered his masterpiece, is an attempt to fuse a subjective stream of consciousness with an objective plot (some revolutionaries’ fake bomb attack), some guiding ideas, and a vision of the city as a living entity (Terras 1991: 483). Chekhov was interested in the philosophy of Russian history found in Bely’s novel, which coincided with his own thinking about the phases of civilization and the end of the old world. In Chekhov’s productions the theme has been defined as “the mystical Time, the disintegrated vacuum into which the world has collapsed when the time is out of joint (Hamlet), and when time has come to an end (Petersburg)” (Kurach 2010: 95).

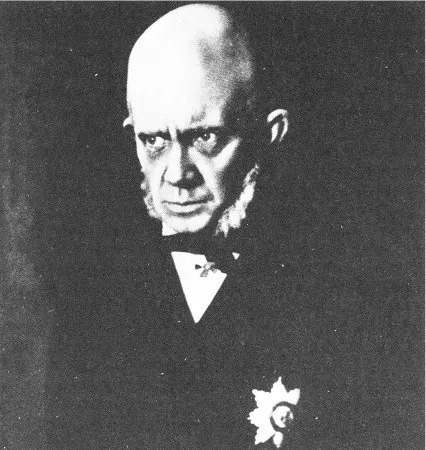

Chekhov took on the task of dramatization of the novel and was to play the main role of the old Senator Ableukhov (Malmstad 1986: 205). Although the “official” directors were Serafima Birman, Vladimir Tatarinov, and Aleksandr Cheban, the artistic decisions in Petersburg (as in Hamlet) were made by Chekhov, as his fellow actors have confirmed (Glumov 1977: 139). His team devised an independent interpretation of the dramatic material. While being keen on the work in the theatre, Bely nevertheless noted with irritation that his drama was at times used as a means of developing acting methods: “[T]hey lay emphasis on the development of the actors’ consciousness, not on achieving something for the audience” (Lavrov and Malmstad 1998: 347). Chekhov stresses the importance of the rehearsal work: “All of us who took part in this performance sought an approach to the rhythm and meter in relation to movement and the spoken word” (2005: 109). In some scenes the pedagogical tasks of developing the actors’ movements and musicality were predominant. Chekhov’s conception was “to sketch an outline of light and dark motives, and the characters’ position in them” (Lavrov and Malmstad 1998: 320). The sets created a hallucinatory world: mobile curtains marked undefined places, and projections were used instead of backdrops (Kurach 2010: 90–91). Chekhov played the Senator, a lonely, tragedic old man, who is gradually stripped of his humanity by the futility and mindless routine of life and convention. The premiere was not a success with the critics or the audience. In the opinion of Soviet theatre historian Konstantin Rudnitsky, in the “collective creative work” only Chekhov’s acting stood out (1988: 193). It was, however, remarkable that Bely’s symbolist and antirevolutionary Petersburg could be staged in Soviet Russia in 1925, and it ran almost until Chekhov’s emigration in 1928.

Figure 1.1 Michael Chekhov as Senator Ableukhov in Andrey Bely’s Petersburg (1925) at the MAT 2, directed by Michael Chekhov. (Private Collection. Courtesy Liisa Byckling.)

During the first few years of his directorship in Moscow, Chekhov succeeded in implementing his ideas for the theatre. Spiritual insights were applied in a specific and practical way in both exercises and productions. In MAT 2 the acting style can be defined as a psychological grotesque in which the character-mask emerged when the psychological portray...