![]()

Part I

Tools

![]()

1

The market for video games

In this first chapter we turn our focus away from why we develop video games and ask instead for whom we develop video games. We argue that successful marketing means turning to consumers before even starting development. Successful video games, in terms of building a business, are not built for ourselves or our peers – they are built for a consumer audience that will gladly pay for them. This is the so-called marketing-focused process as opposed to a product-focused approach. First we start with the consumers and segment them into target groups. We continue by positioning our game title within this segmentation. We end this chapter by explaining how we can take into account the various types of buying behaviour by analyzing the buying-decision process that drives different behaviour.

Learning objectives

- To understand the difference between a product-focused game development process and a marketing-focused game development process

- To learn the basic processes of identifying the consumers of your game

- To recognize the fundamental properties of consumer behaviour

Introduction

We believe that the most important person in the business of making video games is the consumer or gamer, as the consumer is usually referred to in the video game industry. No matter your dreams or aspirations, this is the person for whom you are developing games. This is the person who is willing to spend time and hard-earned money to buy your games. It makes sense to develop games with that specific person in mind, incorporating what this person will want to see in the game while it is planned. There are today processes in most game studios to deal with this aspect, including experience from developing other games and agile project models. In this chapter we have a look at how game development benefits from relating to consumers as future market possibilities. This includes generating knowledge about consumers, using this in the development of games and in the end communicating to these consumers.

Games for whom?

Video games are part of the cultural industry. They are cultural products and something that many of us interact with on a daily basis. The result of this categorization is that both production and consumption of games are assumed to be different from those for other products. That is, games are compared with music, movies and novels – instead of toothpaste, bikes or computers. With the latter products there is a clear relation between developers and consumers. These also assume development of goods to satisfy different needs and wants (more about this later). The relationship to cultural products is a bit more complicated, as the motivation to both produce and consume culture is different from using, let’s say, toothpaste. What all cultural products have in common is that they inhabit symbolical value about society – love, friendship, conflict, money or other things that mean much to us in our societies.

Figure 1.1 Different consumers for cultural products

When looking at the cultural industries as a whole, there are three different potential consumers for what is developed: (1) oneself, (2) peers, (3) consumers (see figure 1.1). It also appears that it does not matter very much what type of culture we are talking about. There are today both cultural and technical possibilities to engage with a lot of cultural productions – for different reasons. Throughout your education or working experience, we expect that you also have had the same experience. There are persons who develop games for themselves. The person developing the game is then also the main audience, and the reward of viewing and interacting with the game is the sole purpose of development. Games are here seen as constructed to materialize an emotion, viewpoint – or whatever one wants to express with the game. This can be compared with the saying “art for art’s sake”, that is, art has no meaning but itself. It is important that the development process starts with the individual and end with the individual. There are also games that are produced for a smaller number of persons, mainly colleagues or other persons in the games industry. The reason for developing this game is to generate credit from persons within the industry and to show off the capability of the person(s) who has made the game. We all know the importance of portfolios for future projects or future employments, so it makes sense to communicate within the industry, to one’s peers and colleagues, in order to make a name for oneself.

Now, we can agree that both of these reasons for making games are in themselves legitimate and respectable reasons for making games. We all appreciate video games as a medium for visualizing and communicating cultural value, and entertainment. But when it comes to building a business for video games, we believe that the focus needs to shift from oneself and one’s peers to consumers. As described in the model, this is the third possible audience for games. This means moving from one’s own evaluation on game quality, moving away from peers and colleagues and moving into a consideration of what consumers might enjoy and prefer. We realize that this sounds suspicious and many times it is hard to do in practice. But the possibility to generate sales and a sustainable game development business increases if you know who you are developing games for, why these consumers should be interested in your game and how you best communicate with these consumers.

“If we build it, they will come”

There are, in general, two different processes that function as rationales for any development project: a product-focused process and a marketing-focused process. This is the case for both the video game industry and for other industries. In these two processes a product is developed either looking internally (in the company to see what could successfully be produced) or externally (to determine what consumers are looking for). A product-focused process starts with the skills and manufacturing possibilities that exist in the company. This can be viewed as a traditional engineering starting point. For example a technical idea is developed as an innovation. The rationale is that the development is driven by the competence in the company and what possibilities these have for developing the idea. Once the development is done, it is a matter of selling – hard selling! – of finding the customers who are willing to buy what has been developed. We call this perspective “if we build it, they will come.”

This process is quite common among a large number of industries, not least in the video game industry. There is a belief that if a game is just good enough according to the developers themselves, the customers will buy the game. Unfortunately, this process has a risk of failure as the gap between the game and the expectations from consumers can be quite wide, resulting in the game drowning in the flood of games published each month and subsequently generating low sales. There are good things to say about this approach, for example the possibility to innovate and push technological boundaries without pressure for commercial use or the fun of making a game for oneself and not giving a toss about what anyone else thinks. Quite a few products that we today have on the market have come about this way, and if there are possibilities to pursue this focus it can result in good products – games and game technology. Our experience, however, is that many start-ups do not have the financial possibilities or the experience to commercialize ground-breaking innovations. The gap between the game and market expectations can become too wide and a hard sell of the game becomes problematic as consumers try to understand what the game is all about.

Some of you might object at this point: “What about Mojang?” (or any other game whose developer obviously did not give a toss about the consumer). Its producers managed to develop a game out of pure belief and hit the big jackpot. And yes, there are a few games that have followed this trajectory. These are brought forward as examples of people who got away with building something in their basement that they were convinced would be a great game. We all love those stories! But, for the thousands of games that generate low sales following the same belief we would recommend a marketing-focused process.

A marketing-focused process

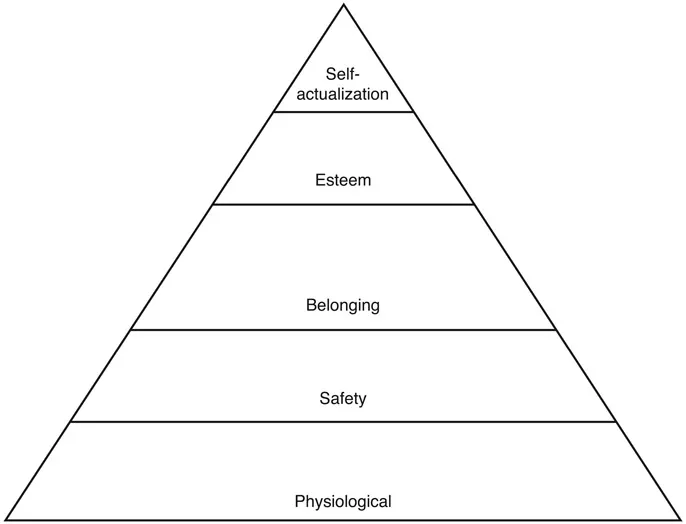

A marketing-focused process starts with the consumer. It starts with asking about the needs and wants of the consumer at whom you are aiming. In marketing it is argued that we all have a number of basic needs that can be sorted into five categories (see figure 1.2): physiological (food, water, sleep), safety (security of body, employment, resources), belonging (friendship, family, intimacy), esteem (self-esteem, confidence, respect) and self-actualization (morality, creativity, spontaneity). According to this model one cannot create needs; these are inherent in being human and fixed in time and space. But, as we are sure you suspect from your interaction with marketing this far, that is not the whole truth. As a conceptual framework for thinking about games and the need they fulfill, the model makes sense – food is more important than games. But, if we depend too much on models like this, we miss the facts that needs are culturally dependent: they vary according to where we live, how we are raised, who we are friends with and all other aspects of our lives. But just as our lives change, so do our needs.

One example that very well highlights this is the Tamagotchi. When Bandai developed the Tamagotchi in 1996 it did not create a need to care for electronic pets; it instead created an electronic device that would speak to the need for belonging and caring. Although the need for belonging can be satisfied in a number of different ways, this is where different wants come into play. It is possible to create a number of different wants in order to satisfy needs. The most obvious example is our physiological needs, for example thirst. This can be satisfied in many different ways, such as with water. But creating a beverage that the customer wants each time he or she is thirsty is beneficial for a producer. Instead of thinking “I’m thirsty,” one thinks, “I’m thirsty for a Coke,” for example.

Figure 1.2 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

In a marketing-focused process, consumers’ needs and wants are inputs to the development of a product. Using knowledge from consumer behaviour, from preferences in existing products, and from marketing research, it is possible to construct an understanding of what kind of games a customer would like to see. What are the patterns for games right now in a specific market? Are there any games on the market that seem to attract much attention? What are the behaviours of current gamers? These questions can generate a good picture of those a game is developed for. Of course, it is not possible to develop a game on the basis of this knowledge alone. The mission of the company or ambitions to drive new and innovative genres have to be taken into account. Consumer knowledge thus has to be related to knowledge and ambitions inside the company – both the developer’s and the publisher’s.

The reason we argue for a marketing approach when developing video games is that both the development process and marketing communication will thus have clear aims. They support each other as the company develops games that consumers are more likely to buy.

Consumer–customer

We hope that by now it is quite clear that knowing for whom you are developing games and how you communicate with these persons is pivotal. We have been talking exclusively about the consumer, but there are in fact a number of different persons involved in buying games. We primarily tend to think and talk about the person who is playing games, that is, the gamer. In marketing terminology this is the consumer – the person consuming a product or service. Although this person is the focus, as it should be, there are reasons to expand our view and include other roles to which we have to relate when developing video games. The term “customer” is many times used interchangeably with “consumer”. Although they can refer to the same person, the meaning is slightly different. Whereas the consumer consumes, the customer is entering into an exchange relationship for games; that is, a customer buys games. As many of us today are buying games online, we are the customers of publishers, but we are also consumers as we are playing the games. Of course, there are cases when games are purchased to be given as presents and parents buy games for kids. So, in the end, who are you to communicate with when developing games?

Segmentation

In order to develop a game aimed for a specific consumer or customer, we do of course want to know as much as possible about that person or persons. This is where the process of segmentation starts, in order to construct knowledge about consumer behaviour – what games are preferred and how that person buys and plays games. A market segment is a group of consumers who respond in a similar way to a given set of marketing efforts. Traditionally the segments that have dominated the game industry have been hard-core and casual gamers, or people organized by dimensions such as gender or age. Although this rubric categorizes how the person plays games (or so we think) and how engaged that person is, it still remains a rather crude road map for making games.

In marketing segmentation we use a number of different dimensions in order to construct different segments of consumers. These dimensions are cultural, social, personal and psychological (see figure 1.3). The cultural dimensions are the most basic determinant of a person’s wants and behaviour. We all grow up in a specific culture that we share with those around us. We are thus socialized into a setting when we grow up and later also when we meet friends and colleagues. But we can also think of culture as consisting of smaller groups, often referred to as subcultures. These comprise a number of persons who share values and interest that are not part of mainstream culture.

The social dimension concerns how we relate to other persons. We humans are social beings, that is, we like to spend time with other humans. And when doing so we affect others, just as they have an effect on us. Just think about whom you consult when buying a video game or any other product for that matter. It could be your friend, your colleagues or social media. In that way word of mouth is one of the most powerful influences on people buying video games. Using it as a tool is sometimes also referred to as buzz marketing. The point is here to identify an opinion leader in a social setting, a person who has high social capital and is trusted by many, and have that person create a buzz for a specific product.

Figure 1.3 Factors influencing consumer behaviour

The personal dimension is related to the situation of a particular person. It includes how old the person is and in what phase of life. What occupation does the consumer have, and what does his or her economic situation look like? On the personal aspect it is also possible to draw out what kind of personality and lifestyle the person has. Independent of the fact that we indeed are social beings, we also have individual personalities that affect how we relate to the world. This affects how we, as consumers, buy and play games. Many of these factors have an impact on this. You may be a poor student with ample time but little money or a person with a well-paid job but little time to play. The concept of lifestyle is also worth exploring a bit, being something of a favourite concept in many marketing settings. Included in lifestyle are a number of different traits. It is thought persons share attitudes and beliefs within that lifestyle. For example we can assume that Live Action Role Play is a lifestyle. This builds on shared beliefs about certain behaviours and about relations to popular culture and to products that support this lifestyle. So as a LARPer you can recognize others within that same lifestyle through items and behaviour. Other examples include metal-heads, skaters and hipsters.

The last dimension...