![]()

1

Introduction

Darren Robinson

This introductory chapter begins with a historical perspective, charting the growth in global population and the urban fraction of this population and discussing what facilitated this growth. We then consider the environmental and societal impacts of mass urbanization and outline some of the challenges that await us in light of future forecasts of the global population, the urban fraction of this population and the resource intensity with which these urban inhabitants maintain and improve upon their standard of living with greater equality.

To help us to address these challenges we need models with which we can test hypotheses for improving urban sustainability. To help understand the attributes that such models need to possess, we then ask and attempt to respond to the seemingly trivial question: how do cities function? In this we consider both environmental and socio-economic factors.

We close this introductory chapter by describing the structure of this book that has been prepared to help us to understand how we might model cities in all of their complexity and optimize their sustainability.

1.1 Urbanization and the environment

As Sachs describes in his excellent book Common Wealth (Sachs, 2008), human development can be broadly grouped into four epochs:

1 <10,000BC: hunter-gatherer.

2 8000BC to AD1000: primitive agricultural.

3 AD1000 to 1830: pre-industrial.

4 >1830: industrial.

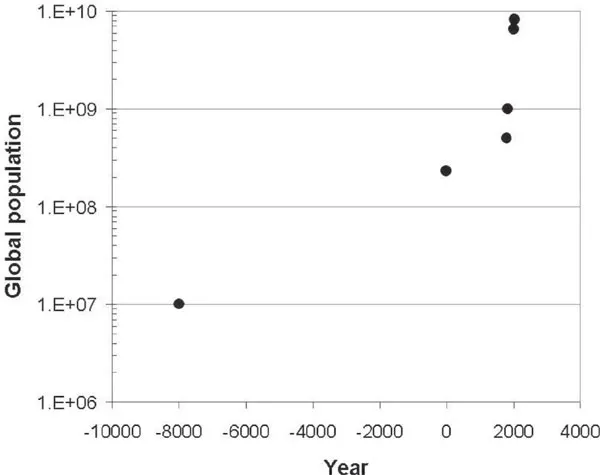

For the first 90,000 years or so of human existence, the human population was fairly stable, being limited by the ability of small groups to hunt and gather their foodstuffs within complex and competitive ecological systems. Then, around 10,000 years ago, human society learnt to tame its environment; appropriating natural, often forested, ecosystems to convert solar energy into foodstuffs that could be consumed either directly or indirectly through domesticated animals. It was during this period that the first substantial urban settlements started to form, as the carrying capacity of fertile land was increased. With increased trade came also the transfer of knowledge regarding the more efficient exploitation of land: better crop choices, irrigation techniques, soil management etc. Surplus food could thus be used to sustain urban dwellers engaged in manufacturing and services. And so both rural and urban settlement sizes grew, but within the limits imposed by the agricultural techniques being employed. Infectious diseases, which were more easily propagated in denser settlements, also curbed population growth. Nevertheless, there was a steady increase in population size up to the dawn of the industrial revolution (Figure 1.1.1) at which around 10 per cent of the global population was urbanized.

Figure 1.1.1 Approximate global human population: 8000BC to AD2030

Source: After Sachs (2008)

The industrial revolution marked the transition from settlements that were limited by the largely manual exploitation of renewable resources, in a relatively sustainable way, to the use of solar energy embedded in fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas). Machines were used to increase the area of land that could be exploited by farmers; chemical processing, in particular the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen into nitrogen-based fertilizers, increased the productivity of land as soil nutrient levels could be artificially increased; railroads, barges and ocean freight enabled products to be transported over large distances.

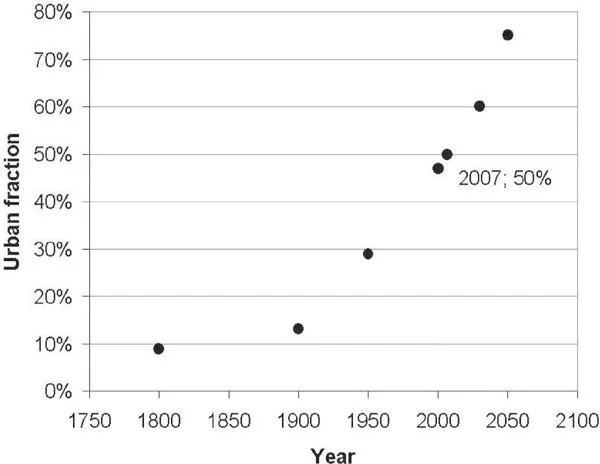

This industrialization has had two consequences. First, the dramatic increase in both the area and the carrying capacity of land being exploited for agricultural purposes has facilitated a dramatic increase in the global population. Second, it has enabled a far greater proportion of this population to reside in urban settlements, such that the urban fraction of the global population has increased more or less linearly from around 13 per cent in 1900 until parity was achieved in 2007: the point at which half of the global population was urbanized (Figure 1.1.2).

Figure 1.1.2 Growth in the urban fraction of the global population

Source: After Sachs (2008)

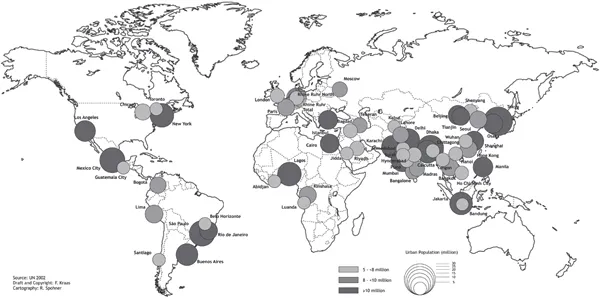

Equally startling is the increased size of urban settlements, to the extent that there are now some 23 mega-cities accommodating in excess of ten million inhabitants (Figure 1.1.3)|

Figure 1.1.3 Global distribution of mega-cities

Source: After Kraas and Sterly, 20081

But what are the consequences of this dramatic urbanization and the intensive exploitation of arable land to support it? Well, these are both global and local. From a global perspective, of most concern are the environmental consequences arising from the intense exploitation of natural resources. Most topical is the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration from its pre-industrial level of 280 parts per million (ppm) to its current level of around 380ppm; which is almost undoubtedly changing our climate. But also of importance is the irreversible destruction of virgin natural habitats and ecosystems, the depletion of natural mineral resources, the over-exploitation of food (particularly marine) stocks leading to species extinction, soil and water pollution due to excess nitrogen fixation, and so on.

From a local perspective, the high density of modern urban settlements also leads to a harmful concentration of pollutants into the air, soil and water compartments of the geosphere. Other concerns are socio-economic. Both the size of cities and the distribution of wealth within them are thought to follow a Pareto (power law) distribution, so that the majority of wealth is owned by a small number of people and the majority of people are poor. This inequality in the distribution of wealth can lead to social tensions, even violence, and ill health linked to poverty. Diseases are also more easily spread, due to the close proximity of urban dwellers. But cities also provide great opportunities for wealth creation and corresponding improvements in lifestyle, for rich social exchanges, for education etc. Indeed, these are the very sources of attraction.

It is for this reason that almost all of the projected increase in the global population (by a further 1.7 billion to 8.2 billion) up until 2030 is expected to be accommodated within urban settlements, at which point some 60 per cent of the global population is expected to be urbanized (UN, 2004). But the population of so-called ‘developed’ countries, which is relatively stable, is already around three-quarters urbanized. Further growth in this urban fraction is thus expected to be modest, so that the majority of the forecasted population growth is expected to be accommodated within the cities of ‘developing’ countries, within which considerable economic growth is also forecast.

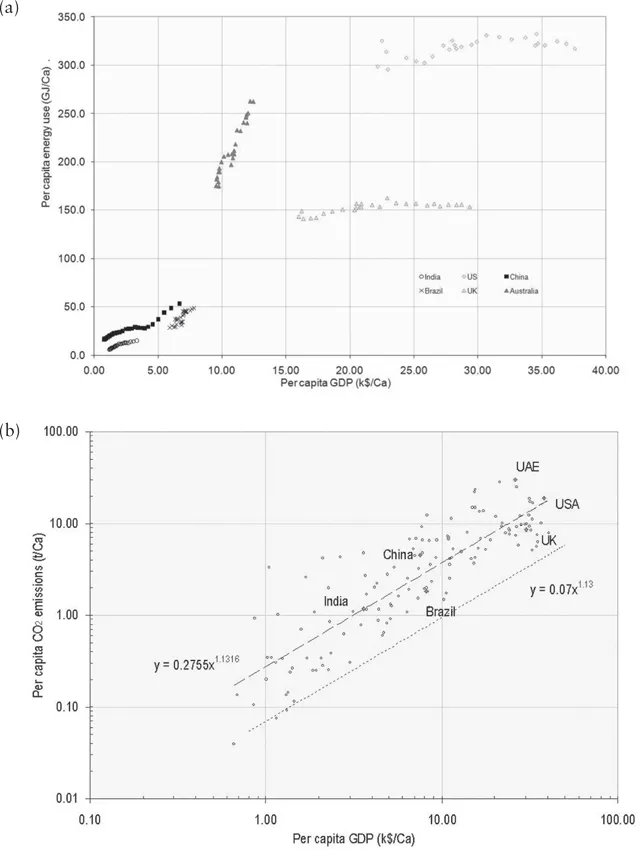

Somewhat disconcertingly, population (P) and economic activity (A) as well as the technology used to support economic activity (T) – environmental impact per unit of income – are thought to be proportional to environmental impact (I): I ∝P.A.T. Thus, with no radical technological changes the environmental impacts of our future population are set to increase considerably. In corroboration of this relationship, Figure 1.1.4a presents the relationship between per capita economic growth and per capita energy consumption for a range of countries and how this has changed with time. The per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of countries such as China, India and Brazil, which are developing at an astonishing rate, is expected to increase significantly with a corresponding impact on per capita energy use and emissions. This is of particular concern because India and China alone accommodate some 38 per cent of the global population.

Figure 1.1.4 (a) Per capita energy use and GDP and (b) per capita carbon dioxide emissions and GDP

Source: Data in (a) from www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/international/energyconsumption.html and www.iea.org/co2highlights/. Data in (b) from www.iea.org/co2highlights/

It is crucial then that the environmental impact per unit of income T of our future urban dwellers, in both developed and developing countries, is considerably reduced (as for example in Figure 1.1.4b). To understand how this might be achieved we should first better understand how current cities make use of the resources they consume.

1.2 How do cities function?

In this section we propose a conceptual framework for understanding how cities function as well as how they may evolve with time. This is intended to set the scene for understanding how we may approach the modelling of cities, define their sustainability and test strategies for improving on this sustainability.

1.2.1 Environmental factors

In order to understand how cities behave physically, it is helpful to consider the thermodynamic concept of entropy S. Entropy is a measure of the dissipation of order. Entropy increases as the thermal disorder of a substance (the thermal motion of its atoms) becomes more vigorous and as the positional disorder of this substance (the range of available positions of its atoms) increases. Thus if we heat the air in a room, the entropy of this air (the thermal motion of its molecules) will increase. If we now open the door to an adjacent room, these air molecules will be distributed over a wider volume (positional disorder increases) so that once again entropy is increased. Over time this energy will eventually be dissipated to the environment surrounding these two rooms, so that entropy is further increased. This is known as the arrow of time: in any isolated physicochemical system, entropy always increases (order is always dissipated) until equilibrium is reached.

But on observing the mysteries of life, Erwin Schrödinger (1944) noticed that we human beings, in fact all living organisms, do not obey this law. During the early stages of our life, as our cells divide and we grow, our internal order is preserved or increased (dS < 0); we defeat the arrow of time. We achieve this by exchanging entropy across our system boundaries: we take in food and oxygen and export waste and carbon dioxide: dSe(in) < dSe(out) so that overall dSe < 0. In other words, and as coined by Schrödinger, we consume negative entropy, negentropy. Thus, although entropy is produced internally due to irreversible internal processes dSi > 0, our body may be maintained in a moreor-less stable state (dS = dSi + dSe ≈ 0), or indeed we may increase in structural order (dS < 0). We are thus an open system. This openness, and the presence of flows, also implies that we are a non-equilibrium system: although the entropy of isolated physicochemical systems tends to evolve irreversibly to equilibrium (dSi > 0, which in our case would imply death), open systems may be maintained in non-equilibrium states. Indeed, Schneider and Kay (1994) suggest that the more energy that is pumped through a system, the greater the degree of organization that can emerge to dissipate this energy. They go on to suggest that the two processes are inseparable, so if a structure is not ‘progressive’ enough it will be replaced by a better adapted structure that will use the available energy more effectively. Thus, we humans have evolved into highly progressive open non-equilibrium thermodynamic systems; we maintain organized non-equilibrium states due to dissipative processes (Nicolis and Prigogine, 1977).

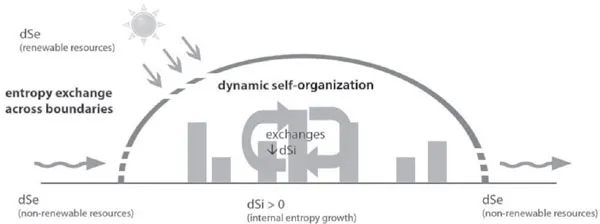

Analogously, our cities may increase in structural order with time, so that their entropy may be reduced. Once again, this is achieved by the exchange of energy and matter across their boundaries (Figure 1.2.1). Entropy is produced within our cities due to irreversible internal processes, such as the combustion of fuel to heat buildings. In principle this internal production may be reduced by coupling processes, but we will come back to this later. Solar energy, fossil fuels, electricity, constructional materials etc. may be imported into our system, while waste products (pollutants) are exported. In common with the metabolism of human beings, we may call the processing of these resources to sustain city life urban metabolism, after Baccini and Brunner (1991).

Figure 1.2.1 The city as a conceptual open thermodynamic system

Source: Author

But this urban metabolism is highly inefficient. Indeed Erkman (1998) has likened the metabolism of cities to that of the first primitive ecosystems to exist on earth. The organisms in such ecosystems live...