![]()

PART I

The One Best System in Microcosm: Community and Consolidation in Rural Education

“Want to be a school-master, do you? Well, what would you do in Flat Crick deestrict, I’d like to know? Why, the boys have driv off the last two, and licked the one afore them like blazes.” Facing the brawny school trustee, his bulldog, his giggling daughter and muscular son, the young applicant, Ralph Hartsook, felt he had dropped “into a den of wild beasts.” In The Hoosier School-Master, Edward Eggleston pitted his hero-teacher Hartsook against a tribe of barbarians and hypocrites, ignorant, violent, sinister, in a conflict relieved only by a sentimental love story and a few civilized allies. Across the nation, in Ashland, Oregon, a father named B. Million wrote a letter to his son’s teacher, Oliver Cromwell Applegate:

Sir:

I am vary sorry to informe that in my opinion you have Shoed to me that you are unfit to keep a School, if you hit my boy in the face accidentley that will be different but if on purpos Sir you are unfit for the Business, you Seam to punish the Small Scholars to Set a Sample for the big wons that is Rong in the first place Sir Make your big class set the Sample for the little ones Sir is the course you Should do in my opinion Sir The imaginary Ralph Hartsook and the real Oliver Cromwell Applegate triumphed over their adversaries, but in common with other rural teachers they learned some meanings of “community control.”1

Community control of schools became anathema to many of the educational reformers of 1900, like other familiar features of the country school: nongraded primary education, instruction of younger children by older, flexible scheduling, and a lack of bureaucratic buffers between teacher and patrons. As advocates of consolidation, bureaucratization, and professionalization of rural education, school leaders in the twentieth century have given the one-room school a bad press, and not without reason. Some farmers were willing to have their children spend their schooldays in buildings not fit for cattle. In all too many neighborhoods it was only ne’er-do-wells or ignoramuses who would teach for a pittance under the eye and thumb of the community. Children suffered blisters from slab seats and welts from birch rods, sweltered near the pot-bellied stove or froze in the drafty corners. And the meagerness of formal schooling in rural areas seriously handicapped youth who migrated to a complex urban-industrial society.

At the turn of the century, leading schoolmen began to argue that a community-dominated and essentially provincial form of education could no longer equip youth to deal either with the changed demands of agriculture itself or with the complex nature of citizenship in a technological, urban society. Formal schooling had to play a much greater part—indeed a compulsory and major part, they believed—in the total education of the country child just as it did for the city pupil. With certain modifications dictated by rural conditions, they wished to create in the countryside the one best system that had been slowly developing in the cities. And while they justified their program as public service, educators also sought greater power and status for themselves.

Because professional educators have dominated writing about rural schools, it is difficult to look at these institutions freshly from other perspectives. Schoolmen saw clearly the deficiencies but not the virtues of the one-room school. Schooling—which farmers usually associated with book learning—was only a small and, to many, an incidental part of the total education the community provided. The child acquired his values and skills from his family and from neighbors of all ages and conditions. The major vocational curriculum was work on the farm or in the craftsman’s shop or the corner store; civic and moral instruction came mostly in church or home or around the village where people met to gossip or talk politics. A child growing up in such a community could see work-family-religion-recreation-school as an organically related system of human relationships. Most reminiscences of the rural school are highly favorable, especially in comparison with personal accounts of schooling in the city. But creative writers like Sherwood Anderson, Edgar Lee Masters, Hamlin Garland, and Edward Eggleston have testified that life in the country could be harsh and drab, the tribe tyrannical in its demands for conformity, cultural opportunities sparse, and career options pinched.2

Here I shall look at some of the latent functions of the rural school which help to account for the differences in perspective of professional educators and local residents; examine the complex interaction of teacher and community; and inspect the “Rural School Problem” as perceived by educational reformers at the turn of the century. This transformation of rural education into a consolidated and bureaucratized institution reflected, and in microcosm illuminated, a broader change in educational ideology and structure. Beginning in the cities, this organizational revolution set the pattern for public education in the twentieth century, in the countryside and metropolis alike.

1. THE SCHOOL AS A COMMUNITY AND THE COMMUNITY AS A SCHOOL

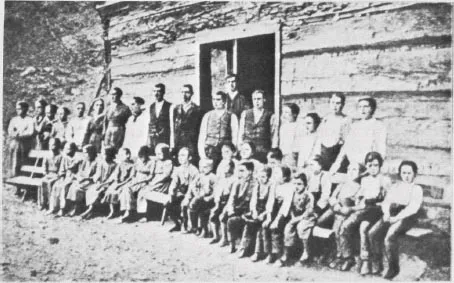

During the nineteenth century the country school belonged to the community in more than a legal sense: it was frequently the focus for people’s lives outside the home. An early settler of Prairie View, Kansas, wrote that its capitol “was a small white-painted building which was not only the schoolhouse, but the center—educational, social, dramatic, political, and religious—of a pioneer community of the prairie region of the West.” In one-room schools all over the nation ministers met their flocks, politicians caucused with the faithful, families gathered for Christmas parties and hoe-downs, the Grange held its baked-bean suppers, Lyceum lecturers spoke, itinerants introduced the wonders of the lantern-slide and the crank-up phonograph, and neighbors gathered to hear spelling bees and declamations.3

Daily in school season, children could play with one another at noon, sliding on snowy hills or playing blind man’s bluff with the teacher on a bright May day. “The principal allurement of going to schools,” said one student, “was the opportunity it afforded for social amusement.” For ranch children growing up on the dry plains of western Texas or eastern Wyoming, separated from their neighbors by many miles, school often provided the only social contacts they had outside the family.4

Indeed, sometimes the school itself became a kind of young extended family. When Oliver Cromwell Applegate taught in Ashland, four of his pupils were Applegates; when his niece taught thirty years later in Dairy, Oregon, she found that “the majority of children were my own sisters and cousins.” Students ranged widely in age. A teacher found on his first day of school in Eastport, Maine, “a company including three men . . . each several years my senior; several young men of about the same age, one of whom seemed to have been more successful than Ponce de Leon in the search for the fountain of perpetual youth, for, according to the records of the school, he had been eighteen years old for five successive years”; and from these giants down to toddlers. Mothers often sent children of three and four years to school with their older sisters or brothers. A young one might play with the counting frame of beads, look at pictures in the readers, or nap on a pine bench, using the teacher’s shawl as a pillow. Older boys often split wood and lit the fire; girls might roast apples in the stove at noon.5

But unlike the family, the school was a voluntary and incidental institution: attendance varied enormously from day to day and season to season, depending on the weather, the need for labor at home, and the affection or terror inspired by the teacher. During the winter, when older boys attended, usually a man held sway, or tried to. During the summer, when older children worked on the farm, a woman was customarily the teacher.6

As one of the few social institutions which rural people encountered daily, the common school both reflected and shaped a sense of community. Families of a neighborhood were usually a loosely organized tribe; social and economic roles were overlapping, unspecialized, familiar. School and community were organically related in a tightly knit group in which people met face to face and knew each others’ affairs. If families of a district were amicable, the school expressed their cohesiveness. If they were discordant, the school was often squeezed between warring cliques. Sometimes schooling itself became a source of contentention, resulting in factions or even the creation of new districts. A common cause for argument was the location of the school. “To settle the question of where one of the little frame school-houses should stand,” wrote Clifton Johnson about New England, “has been known to require ten district meetings scattered over a period of two years” and to draw out men from the mountains who never voted in presidential elections. In Iowa, dissident farmers secretly moved a schoolhouse one night to their preferred site a mile away from its old foundation. In tiny Yoncalla, Oregon, feuds split the district into three factions, each of which tried to maintain its own school. Other sources of discord included the selection of the teacher—even that small patronage mattered in rural areas—or the kind of religious instruction offered in the classroom. But more often than not, the rural school integrated rather than disintegrated the community.7

Relations between rural communities and teachers depended much on personalities, little on formal status. Most rural patrons had little doubt that the school was theirs to control (whatever state regulations might say) and not the property of the professional educator. Still, a powerful or much-loved teacher in a one-room school might achieve great influence through force of character, persuasion, and sabotage.

A pioneer teacher in Oregon recalled that a school board member instructed her not to teach grammar, so she taught children indirectly through language and literature. Another Oregon teacher followed the state course of study which required her to have the children write their script from the bottom of the page up “in order to see the copy at the top of the page.” An irate committeeman warned her that “if you don’t have the kids write from the top down, I’ll have you fired.” He won. But when other trustees objected to building two privies—one for boys and one for girls, as the state law said—the same teacher convinced them to comply by showing it would cost only twenty dollars for the two privies together.8

School and Community—A Rural Transaction

Finding his schoolhouse “strewn with bits of paper, whittlings and tobacco” from a community meeting the night before, a young Kansas teacher decided he “would go to that board and demand that the schoolroom be put in sanitary condition, and state the school would not be called till my demands were complied with.” He quickly learned that in this village, where three teachers had failed the year before, educational law might be on his side but the patrons could only be managed, not bossed. “Look with suspicion upon the teacher who tells you how he bosses the school board,” he observed. “He is either a liar or a one-termer, and the probabilities are that he is both.”9

Teachers knew to whom they were accountable: the school trustees who hired them, the parents and other taxpayers, the children whose respect—and perhaps even affection—they needed to win. Usually young, inexperienced, and poorly trained, teachers were sometimes no match for the older pupils. When a principal lost a fight with an unruly student in Klamath Falls, Oregon, it was he and not the student who was put on probation by the board—presumably for losing, not for fighting (which was common).10

The position of the teacher in the tribal school was tenuous. In isolated communities, residents expected teachers to conform to their folkways. In fact if not in law, local school committeemen were usually free to select instructors. With no bureaucracy to serve as buffer between himself and the patrons, with little sense of being part of a professional establishment, the teacher found himself subordinated to the community. Authority inhered in the person, not the office, of schoolmaster. The roles of teachers were overlapping, familiar, personal, rather than esoteric, strictly defined, and official (the same teacher in a rural school might be brother, suitor, hunting companion, fellow farm worker, boarder, and cousin to different members of the class). The results of his instruction, good or poor, were evident in Friday spelling bees and declamations as neighbors crowded the school-house to see the show. If he “boarded ‘round” at the houses of the parents, even his leisure hours were under scrutiny.11

If he was a local boy, his faults and virtues were public knowledge, and a rival local aspirant to the office of village schoolmaster might find ways to make his life unpleasant. If he was an outsider, he would have to prove himself, while the patrons waited with ghoulish glee, as in The Hoosier School-Master, to see if the big boys would throw him out. Romance was sometimes as threatening as brawn. Matrimony stalked one Yoncalla teacher: “It was not the fault of the Yoncalla ‘gals’ that the young Gent . . . escaped here in single blessedness. It was a manoeuvre of his own. He was attacked on several occasions mostly in the usually quiet manner but one time furiously, but he artfully overlooked the gauntlet and was not carried away.” Against the tyranny of public opinion the teacher had little recourse; against the wiles of the scholars he had as allies only his muscles, his wit, and his charm.12

The “curriculum” of the rural school was often whatever textbooks lay at hand. Often these books wedded the dream of worldly success to an absolute morality; cultivation meant proper diction and polite accomplishments. For some children readers such as McGuffey’s gave welcome escape from monotony and horse manure, just as play in the schoolyard relieved the loneliness of farm life. A boy in the Duxbury Community School near Lubbock, Texas, discovered a passion for literature and later became a professor. Hamlin Garland recalled that in Iowa “our readers were almost the only counterchecks to the current of vulgarity and baseness which ran through the talk of the older boys, and I wish to acknowledge my deep obligation to Professor McGuffey, whoever he may have been, for the dignity and literary grace of his selections. From the pages of his readers I learned to know and love the poems of Scott, Byron, Southey, Wordsworth and a long line of the English masters. I got my first taste of Shakespeare from the selected scenes which I read in these books.” Edgar Lee Masters, by contrast, wrote that his school days “were not happy, they did not have a particle of charm.” And a boy in New England wrote in the flyleaf of his textbook: “11 weeks will never go away/ never never never never.”13

Whether these rites of passage into the world of books were pleasant depended in large part on the teacher. Though usually poorly educated, the rural teacher was sometimes regarded by the community as an intellectual. It didn’t take much to convince him that he was a man of letters. A friend of Applegate’s wrote that he had attended a “State Teachers’ Institute, where there was an immense gathering of the literati—no less than eleven men with the title of ‘Professor’—and fourteen with the title of Reverend besides about fifty lesser lights.” Farmers and pioneers were ambivalent about these literati in the...