![]()

CHAPTER 1

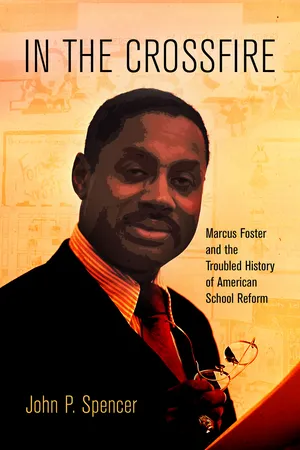

Schooling as Social Reform: Racial Uplift, Liberalism, and the Making of a Black Educator

PUBLIC education has been intimately tied to American dreams of social mobility since Horace Mann helped found the first school system in the early nineteenth century, and it has held an especially potent meaning for African Americans. Initially barred from public schools, blacks not only were denied an avenue of opportunity (and an increasingly important one as the twentieth century unfolded); they were stigmatized as intellectually inferior. As a result, access to education has been at the core of African Americans’ identities as free people, and academic achievement—especially the acquisition of literacy—has been a way for African Americans to transcend racist assumptions and assert themselves as equal citizens.1

Marcus Foster’s upbringing vividly illustrates the obstacles that African Americans faced in pursuing educational achievement as well as the importance they attached to doing so. Foster’s family moved from Georgia to Philadelphia in the 1920s, when he was two or three years old—part of the “Great Migration” of African Americans who left the South with the hope of making a better life in the cities of the North. The migration changed the cities and their schools—and, for blacks hoping to escape racism and Jim Crow, the changes were not always promising. Foster went to public schools during the 1930s. When he graduated from high school in 1941, the system was more segregated than it had been when he started. This was no accident. The de facto segregation of the North may not have been imposed by law (de jure), as it was in the South, but it was a product of intentional actions, nonetheless. As African Americans became a larger presence in Philadelphia and other cities, whites worked to contain them in separate neighborhoods, workplaces, and schools. In those cases in which black children did end up in the same schools as whites—especially at the high school level—they faced discrimination in the form of separate curricula, lower expectations, and sometimes overt hostility from white teachers. And if, after all that, black students managed to make it to graduation, they were likely to face job discrimination that prevented them from applying their schooling. For many African American youths who faced such dismal educational and employment prospects, the streets, the poolrooms, and the underground economy became alternative arenas for achieving an identity.2

Marcus Foster was a product of this gritty South Philadelphia subculture. As a teenager, he wore a zoot suit and was a leading member of a social club, or gang, called the Trojans. He could “hold his hands up” as a street fighter, according to his lifelong best friend, Leon Frisby. Frisby was a member of Club Zigar—“you had to smoke a ‘stogie’ and drink a lot of wine to get in”—and he remembers meeting Foster at a club dance in a gymnasium that doubled, at night, as “Club Benezet.” The two boys went to the same junior and senior high schools, but most of Frisby’s memories of Foster from this period revolve around parties, “rumbles,” and life in the streets. “We were worldly,” Frisby laughs.3

At the same time, though, Marcus Foster was an excellent student whose achievements were part of a larger dream of racial progress and self-improvement through education—a dream held dear by African Americans since the days when slaveowners had made it a crime for them to be literate. Foster was immersed in that educational legacy by a mother who named him after the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius and nurtured a family culture of striving and learning. And as she imparted the legacy of African American achievement, Alice Foster also endowed her children with forms of cultural capital—especially literacy in Standard English—that would help them succeed in a school system run by white educators.4 Young Marcus was as ambitious, competitive, and as proud in school as he was in the activities of the Trojans. He graduated with honors from South Philadelphia High, won a scholarship to all-black Cheyney State Teachers College outside of Philadelphia, and made one of the few legitimate, upwardly mobile career moves available to a young black man: he became a teacher. And he did so not because of, but in spite of, a public school system that expected little of him and other black students.

Foster’s mixed identity—his immersion in street life and his drive for mainstream success—had at least two implications for his future as an educator. First, he was a living example of how education could be a ticket to social mobility for an African American boy of limited means. In spite of the obstacles and distractions that he faced—including some within the schools themselves—Foster and his family prioritized education both as a path to college and a career choice, and this would prove to be the key to a life of financial security. At the same time, though, Foster’s “worldly” background gave him a basis for understanding just what a challenge it was for many urban students to achieve success in education and life. Foster was not the straitlaced young man that his mother or the Cheyney president Leslie Pinckney Hill wanted him to be, and this, as much as his more respectable accomplishments, was part of why he held such promise as a mentor and educator of urban youth.

Another factor that shaped Foster’s rise to educational leadership was timing. During the World War II era when Foster was at Cheyney, social changes in the larger society, including a “Second Great Migration” of southern blacks to cities like Philadelphia, gave wider urgency to black education, making it a more mainstream cause. The 1940s gave rise in the northern cities to a new racial liberalism that predated the southern civil rights struggles of the 1950s. As historians have begun to show, white and black liberals joined forces during and after the war to fight discrimination in the workplace and in private housing markets.5 Yet racial liberals did not focus solely on jobs and housing; in the 1940s and especially in the 1950s, they also began to move urban schools and educators toward the center of the struggle against racial inequality.6 Educators, reformers, and other city leaders began to address racial inequality in urban schools as a result of “intergroup tensions” that escalated during World War II; as blacks entered the city in larger numbers and whites resisted their integration into urban life, some liberals looked to the schools for solutions. Education took on new importance for Americans who increasingly conceived of racial inequality as a vicious circle of white prejudice and black social pathology. Hoping to break this cycle and extend equal opportunity to African Americans, racial liberals created school-based “intergroup education” programs aimed at eradicating “prejudice.”7

Foster’s African American upbringing had a different educational focus than did the racial liberalism of the 1940s and 1950s: academic achievement and literacy as opposed to the eradication of prejudice. Moreover, as a young educator, Foster was not driven first and foremost by idealistic intentions to uplift his people or fight racial prejudice and inequality; he seems to have been motivated more by a personal ambition to work within the system toward his own professional accomplishments and advancement. As Frisby says, he had to “come out on top” in everything he did.

Still, Foster’s personal path would be shaped and altered by the movement of history. Due to the rise of racial liberalism, his potential to achieve a position of leadership was greater than that of many black men in earlier generations. And due to the rising importance of education within the struggle for racial equality, an up-and-coming black educator like him was on a path to becoming a leader in the larger struggle of his people, whether he intended to be one or not. Foster would have the chance—and the burden—of showing that his personal story of educational achievement and social mobility could be the rule, rather than the exception.

“You Can’t Teach Them Anything”: Separate and Unequal Schooling in Philadelphia

Marcus Foster was born March 31, 1923, in Athens, Georgia, about seventy miles from Atlanta. He was the youngest of five children born to William Henry Foster, a mailman, and Alice Johnson Foster, a schoolteacher. (A sixth child, who died of diphtheria during infancy, would have been the oldest.) The parents separated when Marcus was two or three, and Alice took the children to Philadelphia, where they moved in with her younger sister, Susan, and Susan’s husband John Jordan. “All six of us descended upon them,” laughs Alfred Foster, who was two years older than Marcus, “so growing up in Philadelphia, it was a family of eight.” The Jordans and Fosters initially lived in a small row house at 20th and Gerritt Streets in South Philadelphia; a short time later, they bought a three-story row house at 18th and Latona.8

Foster’s family had its own distinctive reasons for moving north, but the six of them were also part of the Great Migration of African Americans out of the South. Philadelphia had always been an important center of African American settlement, but World War I marked a turning point for the city’s black community. Southern migrants, lured initially by recruiters from the city’s railroad corporations, kept coming of their own volition into the late 1920s, causing the city’s black population to more than double between 1910 and 1930, from 85,000 (5.5 percent of the city’s total) to 220,000 (11.3 percent). The migrants established a more visible presence for African Americans in Philadelphia; while roughly a third of them moved into Center City’s seventh and thirtieth wards, the somewhat isolated black ghetto that W. E. B. DuBois spotlighted in his 1899 study The Philadelphia Negro, most, including the Fosters, branched out into neighborhoods where blacks were still significantly outnumbered by Jewish, Italian, and Irish immigrants.9

Foster’s brother, Alfred, remembers the South Philadelphia neighborhood of his and Marcus’s youth as “very integrated,” full of Italian and Jewish immigrant families with whom the Fosters got along. “Our childhood days were full of activities and pleasant memories. Lots of children and lots of fun playing games—street games like rugby, stickball, and jump rope.” Alfred had heard about, but never experienced, turf battles involving the Italians and the Irish; in his small world, at least in memory, the ethnic and racial groups lived in peace.10

Alfred Foster’s memories suggest a degree of social fluidity in the northern cities that absorbed the Great Migration of southern blacks. Indeed, prior to 1930 the northern cities were actually less segregated than they would become in the four decades thereafter. Still, for migrants who had envisioned the North as the promised land, segregation and second-class citizenship remained a bitter fact of life. Philadelphia was a border city, just north of the Mason-Dixon line, and many of its public and commercial facilities were segregated. Its manufacturing sector went into long-term decline in the late 1920s, depriving the migrants of manufacturing jobs the war only recently had made available to blacks for the first time.

To make matters worse, the newcomers became scapegoats for social and economic problems that coincided with their arrival. Native-born Philadelphians, fixating on a derelict element in the early wave of railroad recruits, blamed the migrants en masse for rising crime rates, a booming underground economy, public disorder, and deteriorating neighborhoods—despite evidence that most of them came from stable families and that many of those who engaged in underground activity did so because the world of legitimate enterprise had shut them out. Some of the southerners’ toughest critics included the so-called Old Philadelphians, or O.P.s—native-born blacks who were eager to maintain the modicum of status and security they had achieved as butlers, caterers, postal workers, ministers, teachers, and, in some cases, professionals. The O.P.s resented the newcomers for stirring up anti-black attitudes.11

Better schooling for their children was a top priority among African Americans who fled the segregated South during the Great Migration. Instead, the migrants faced new variations on an old problem of separate and inferior schooling in a system that stigmatized their children as intellectually inferior. Black children were not a major presence in the Philadelphia schools in the first two decades of the twentieth century; in 1920 they made up only 8.1 percent of the total school population. Black students who did attend school were usually mixed with whites in integrated facilities.12 During the Great Migration, however, the school district began to steer white children away from schools with black children and, in some cases, to build new schools to accommodate the rising black enrollments. Gerrymandering and informal pressure were less overt than Jim Crow, but they produced similar results: roughly a dozen all-black, often under-equipped, elementary schools. Even within junior and senior high schools, which drew from a wider geographic area and therefore remained somewhat integrated, tracking and separate curricula channeled white children into academic subjects and limited black children to the vocational courses that allegedly suited their abilities.13

One of the most potent mechanisms for segregating and stigmatizing black children, whether in separate schools or within the same building, was the battery of new intelligence tests that came into vogue after World War I. Testing put a pseudo-scientific gloss on the idea of racial differences, explaining them as products of natural intelligence rather than discrimination and oppression. Researchers, for instance, drew unflattering conclusions from the presence of “large numbers of big, unschooled, overage southern children in the lower grades,” as one black teacher described the effect of the Great Migration, without considering that the roots of this phenomenon lay partly in the dreadful lack of educational opportunities and expectations for black children in the Jim Crow South. What is more, IQ testing did not always work to a black child’s advantage even when he or she got a high score; in 1924, for example, the Philadelphia High School for Girls segregated all of its black students into the same class, citing IQ scores as the reason, when in fact the girls’ scores ranged from low to high.14 Such practices were all the more likely because the teachers and administrators in Philadelphia’s junior and senior high schools were segregated, too. Using separate eligibility lists, the school district placed black teachers only in predominantly black schools, thus limiting them to the elementary grades. As a result, they were stigmatized as un-fit to teach white children and prevented from working with and supporting older black students.

In the face of such obstacles, black educators, par...