![]()

CHAPTER 1

COMPROMISING TO WIN BLACK TEACHERS’ JOBS

Amid the hundreds of Southern black migrants who arrived in Milwaukee in 1928, William Kelley stood out. While most came to the city without a high school education and searching for factory or domestic work, Kelley had a college degree and had already lined up a position as the new executive director of the Milwaukee Urban League, a social service agency dedicated to resettling rural migrants into their new urban environment. Soon, these migrants would be standing in line to meet him, dressed in his three-piece suit and tie. ‘‘When a Negro comes to Milwaukee,’’ reported the white press, ‘‘he is almost certain to seek William V. Kelley, the person who can best advise him on working opportunities and housing facilities.’’1

Kelley had been groomed for this position with the Urban League. Born and raised in Tennessee, he graduated from Fisk University, the most prestigious black liberal arts college of its time. There he met Dr. George Haynes, the first director of the National Urban League, who also led Fisk’s innovative Department of Social Work. Haynes recognized the need for professionally trained black social workers to coordinate social service and philanthropic efforts in the North, since they had greater familiarity and faith in the black community than did their white counterparts. He tutored Kelley and others in the ways of the Urban League, instructing them to ‘‘leave militancy to others’’ and to use the tools of ‘‘education rather than legislation.’’ Unlike the NAACP, Urban League founders believed that they could be most effective in achieving their objectives through quiet negotiations rather than public protests, and their nonpartisan stance also qualified them to receive desperately needed charitable contributions for their nonprofit agency. League affiliates across the country also dealt with a complicated interracial dynamic:most staff and clients were black, but most board members and donors were white. The organization needed people like Kelley, who could draw upon his interpersonal experiences to navigate through both worlds. After graduating from Fisk, he had experienced the color line in different forms: as a soldier in Europe during World War I, as a factory worker in Detroit, as a college instructor in Oklahoma, and as an Urban League staff member in St. Louis.2

William Kelley, executive director of the Milwaukee Urban League, sought ways of persuading white school officials to hire black teachers during the Depression. From Milwaukee Journal, 26 November 1939; copyright Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Inc.; reproduced with permission.

Immediately after arriving in Milwaukee, Kelley had to redouble his efforts to secure jobs for blacks because the Depression was ravaging the local economy. Milwaukee’s workforce depended heavily on the iron and steel industry. The city had gained national prominence for its machinery products, such as tractors and cranes manufactured by its largest employers, the Allis-Chalmers and Harnischfeger corporations. When demand plunged for these products, the economic crisis hit Milwaukee much harder than comparable cities in the nation. Between 1929 and 1933, the total number of employed wage earners fell 44 percent, forcing white employees into stiff competition for jobs with newly arrived black migrants. As the city’s Urban League employment service director, William Kelley screened migrant applicants and made referrals to white businesses and homeowners who needed inexpensive labor and were willing to consider black employees. Known as ‘‘the Negro’s best bet,’’ Kelley’s office drew nearly 6,000 job seekers in 1930, but only 10 percent found work placements through the League service. When black migrants did find employment, they typically performed the lowest-paid and most unpleasant labor, such as feeding blast furnaces in steel foundries, slaughtering animals in packinghouses, processing hides in tannery lime pits, and scrubbing toilets in white people’s homes. Blacks had to settle for ‘‘the dirty work,’’ as one recalled, ‘‘jobs that even Poles didn’t want.’’3

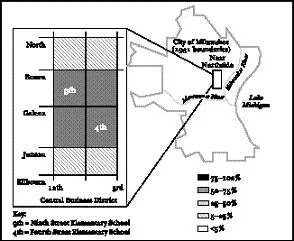

Milwaukee had a tiny black community in the early twentieth century. By 1930, two years after Kelley’s arrival, he counted only 7,500 black residents, merely 1.3 percent of the city population. Both newcomers and old-timers crowded together into an impoverished neighborhood known as the Near Northside. Only ten black families owned their own homes. The vast majority of black residents rented from absentee landlords, and observers judged more than 90 percent of the neighborhood housing stock to be in poor physical condition. White realtors attempted to segregate the growing black neighborhood. In 1924, the Milwaukee Real Estate Board considered a formal proposal to restrict the population to a ‘‘black belt’’ within the city, and although they eventually dropped this measure, white property owners found several ways to achieve this goal. Restrictive covenants appeared in 90 percent of the county property deeds filed between 1910 and 1940, according to one estimate. The typical language expressly prohibited the sale or occupancy of property by ‘‘any person other than of the white race.’’ Most other whites informally agreed not to sell or rent to blacks outside of the Near Northside, maintaining the neighborhood boundaries that carved up the city into white ethnic enclaves. Together, these forces created recognizable, though unofficial, color lines. The city’s central business district formed the southern edge of the Near Northside on State Street, while the eastern and western borders were marked by Third Street and Twelfth Street. The northern edge of the color line inched farther outward, beginning at Galena Street in 1928 and reaching North Avenue by the late 1930s. Over 92 percent of the city’s black population was enclosed within this 120-block neighborhood.4

Yet while most black Milwaukeeans were residentially segregated into the Near Northside, it was not an all-black community at this time. During the 1930s, whites composed approximately 50 percent of the 120-block neighborhood. Even in the census tract with the greatest concentration of black residents, whites still numbered 33 percent of the population. Consequently, when Milwaukeeans looked to their public schools, they did not yet see blatant patterns of racial segregation. Although nearly all black school children attended either Fourth Street or Ninth Street Elementary, both had racially mixed student bodies, enrolling between 35 to 50 percent black students in the early 1930s.Therefore, in the eyes of black community leaders like William Kelley, school segregation was not an issue. Instead, he mobilized around the fact that there had not been a single black teacher in the Milwaukee public school system when he had arrived in 1928, nor for several years later. Working together with his colleagues, Kelley defined black teachers’ jobs as the city’s leading black education reform issue for the next thirty years.5

Black Population in Milwaukee’s Near Northside during the 1930s. Although blacks were largely confined to one area in the early 1930s, they lived among significant numbers of whites, meaning that public schools were still racially mixed. Adapted from Citizen’s Governmental Research Bureau, ‘‘Milwaukee’s Negro Community.’’

Black teachers functioned as the levers for racial uplift during the early twentieth century. Whether one subscribed to the industrial education strategy of Booker T. Washington or the ‘‘talented tenth’’ approach of W. E. B. Du Bois, both relied on black teachers to advance the race. Across the South, black teachers not only provided a steady source of income for the local economy but also held respected positions as moral leaders of segregated communities. Observers consistently argued that ‘‘the genuine teacher knows that his duty is not bounded by the four walls of the classroom. He is dealing with boys and girls to be sure, but he is dealing with something more—with social conditions.’’ Ideal Southern black teachers admonished students to continue their education within the constraints of the system and demonstrated through their own positions that schooling led to higher-status professional work. During the Great Migration of the early twentieth century, when over one million blacks left the South, one of their collective goals was to reestablish black community structures in Northern cities, in part by securing jobs for black teachers. But to do this, Kelley had to persuade white officials who ran the system to hire teachers of his race.6

In Milwaukee, William Kelley and his 1930s contemporaries recognized the dual purpose that schools played in their local struggles. The public schools not only were potential employers of middle-class black teachers but also served as key institutions that socialized black youth into their roles in the city’s racialized labor market. Kelley heard many complaints about white teachers’ low expectations for black students. One survey indicated that Milwaukee teachers and administrators believed that blacks ‘‘indirectly accept’’ their entry into low-level ‘‘Negro jobs’’ because they allegedly ‘‘feel their lot is hopeless.’’ Vocational counselors advised black boys against training in higher-level occupations on the grounds that these jobs would not be made available to members of their race. Perhaps worse, schools taught stenography to black girls but refused to hire them as stenographers in the district’s own central office. Even black students who did well academically discovered that their schooling had little relevance in Milwaukee. Three black teenage girls whose applications were rejected by a dime store were shocked to see those jobs given to white girls from the same high school. ‘‘Those other girls didn’t make any better grades than we did,’’ the black girls reported. ‘‘We used to help one of them with her algebra. If we can’t even get jobs in a dime store, what’s the use?’’ The sum of these experiences socialized black youth to believe that education did not pay, a painful lesson that Kelley sought to interrupt by introducing black teachers back into their world. Once jobs had been gained for black teachers, he believed, both their symbolic and pedagogical influence would help black students navigate their way through Northern white schools and into the workforce.7

During the 1930s, as the economic crisis worsened and white school officials refused to budge, Kelley proposed a compromise that led to the hiring of the first black teachers in permanent positions. Decades later, Kelley’s accomplishments would be ignored by the 1960s generation of black school activists, who branded any concession to segregation as a failure to achieve true equality. Yet black school reform activists from the 1930s (like Kelley) and those from the 1960s (who rejected Kelley) had much in common: they both sought greater political influence over the white-dominated public education system in order to advance the race. This chapter lays the groundwork for later comparisons by focusing on Kelley’s objectives for advancing black Milwaukee and how they were shaped by the historical context of his time.

Black Teachers and Political Power in the Urban North

Through his correspondence and annual meetings with other Urban League affiliates, William Kelley compared the status of blacks in Milwaukee with those in other Northern cities. Table 1.1 illustrates what Kelley saw shortly after his arrival in the city in the late 1920s and helps explain why black teacher employment was such a pressing issue. Cities across the North could be divided into three clusters: those where black teachers taught in all types of schools (white, black, and racially mixed), those where black teachers taught only in segregated black schools, and those that had few or no black teachers.8

Clearly, the size of a city’s black population influenced the number of black teachers employed by its public schools, but it was not the only factor; how black communities translated their numbers into potential votes and the stance they took regarding all-black schooling mattered even more. For example, Pittsburgh’s black population was nearly 55,000 in 1930, roughly comparable to Cleveland, Cincinnati, or Indianapolis. Yet Pittsburgh city schools counted no black teachers at that time. By contrast, Cleveland employed 75 black teachers in black, white, and racially mixed schools, while Cincinnati and Indianapolis employed even more black teachers (146 and 238) in racially segregated schools. In all of these cities, black communities faced some difficult decisions. How should they exercise the limited political clout available to them in the governance of public schools? Should they press for a handful of black educators in a racially mixed system, or for a greater number of black educators in a segregated system? These painful (and heavily contested) decisions, and the tense negotiations with white officials that followed, established black teacher employment as a leading education reform and civil rights issue in Northern cities during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Across the urban North, different combinations of electoral politics and racial compromises shaped black education reform agendas in various ways. In the first cluster of cities (New York, Cleveland, and Chicago), where white politicians actively competed to win black votes, black leaders successfully negotiated to win jobs for black teachers in white, black, and racially mixed schools. New York City, for instance, gained a national reputation for not only hiring the largest number of black teachers but also for assigning many of them to white schools. ‘‘We are very proud of our record here, as you can imagine,’’ NAACP leader Mary White Ovington boasted in 1920 to the Pittsburgh branch, whose city had no black teachers. The Amsterdam News echoed Ovington’s sentiment in the black community and proclaimed in 1934 that New York City was ‘‘the only one among the larger cities of the country which accepts the Negro teacher and pupil on a basis of equality and fair play.’’9

Table 1.1:Black Teachers in Selected Northern Cities, circa 1930

| City | Black Teachers | Black Population |

|---|

| Black teachers in all types of schools | | |

| Chicago | 300 (2.1%) | 233,903 (6.9%) |

| Cleveland | 84 (1.8%) | 71,899 (8.0%) |

| New York | 500 (1.5%) | 327,700 (4.7%) |

| Black teachers in segregated black schools | | |

| Cincinnati | 146 (6.5%) | 47,818 (10.6%) |

| Indianapolis | 238 (12.6%) | 43,967 (12.1%) |

| Philadelphia | 295 (3.7%) | 219,599(11.3%) |

| Few or no black teachers | | |

| Buffalo | 4 (0.01%) | 13,563 (2.4%) |

| Milwaukee | 0 (0%) | 7,501 (1.3%) |

| Pittsburgh | 0 (0%) | 54,983 (8.2%) |

The origins of New York City’s relative success could be traced back to a long history of white politicians competing for black votes. In 1883, black New Yorkers lobbied the state legislature to allow their students the option of attending white schools without sacrificing black-run schools and thereby losing jobs for black teachers. Both Democrats and Republicans passed the bill, since Tammany Hall was fighting hard to sway black voters from the Party of Lincoln. But city school officials temporarily halted the plan by refusing to hire any new black teachers. After gaining sufficient ‘‘political assistance,’’ the first black teacher was appointed to a predominantly white school in 1896, and the numbers of black teachers rose steadily during heated local races. Ever since that struggle, Ovington observed, ‘‘the question of race or color has not been considered in the appointment of teachers.’’ Indeed, New York won fame as the fairest employer of black teachers, but not because city hall had suddenly become color-blind. To the contrary, black teachers secured jobs throughout much of the New York City school system due to intense white political competition to win the black vote.10

Black Clevelanders, despite their relatively small population, also exercised political clout to win jobs for black teachers in white schools. At least thirty-two of the city’s eighty-four black teachers (38 percent) worked in all-white or predominantly white schools in 1930. Political scientist Ralph Bunche attributed these gains to black recognition of the value of ‘‘independent voting,’’ pressuring white Republicans and Democrats to compete for black support in local and state races. During the election of 1926, one black Clevelander reported to the NAACP, ‘‘We supported Democrats and the Republicans alike, depending upon their merits.’’ In the late 1930s, black leaders took advantage of the school board’s desire to pass additional tax l...