![]() Civil society, industry, and regulation

Civil society, industry, and regulation![]()

Editor’s introduction to Chapter 13

In opening this final section on civil society, industry, and regulation, STS scholar David Hess documents the existence of four pathways through which citizen activists can make positive social and environmental change. These are not ideal types of political thought deduced from a theoretical perspective, but types of action that seem to be successful from an empirical perspective on sustainability. These four “alternative pathways” for social change serve as laboratories of innovation that test alternative designs of organizations, technologies, and infrastructures that would enable a transition to a more just and sustainable society.

Hess argues that, in general, established industrial corporations will struggle to undermine environmental regulations and will continue to focus on growth at the expense of the environment. Social movements and other forms of social change action provide a source of ongoing pressure for change and experimentation with alternatives. Through a process of incorporation and transformation, reformers often achieve mixes of partial victory and cooptation.

There are two significant assumptions in Hess’ analysis that are consistent with Dewey’s assessment of The Public & Its Problems: First, the interests of industry are not necessarily congruent with those of the public. In cases where private judgment has adverse consequences for other citizens, the state exists to regulate such actions on behalf of public well-being. But second, the distinction between private matters and those public ones regulated by the state doesn’t cover all possible associations.1 There is a political or experimental space in between where some associations among citizens come into being in order to advocate for norms that are not commonly held. In such cases the public, or “civil society” as Hess prefers, anticipates improved alternative futures and works toward the rational acceptance of new norms by a majority of citizens. The most valued characteristic of a democratic society, for Dewey and Hess both, is the manner in which experimental thought within civil society becomes, through public talk and over time, the norm to be regulated by the state. By imagining a “civil society society,” Hess too argues for the creative power of the public to construct new habits.

Chapter 13

Social movements, civil society, and sustainability politics

Alternative pathways and industrial innovation

David J. Hess

Introduction

A political and sociological approach to sustainability begins with the fundamental question: Is a sustainable society possible within a political and economic system dominated by large, publicly traded corporations? Certainly the greening of industry is occurring, and there are many available technologies that could be scaled up to reverse the crises of global warming, resource depletion, and polluted ecosystems. However, as accumulation theorists have argued, to date the greening of industry takes place within an economic system that emphasizes ongoing growth as measured both by macroeconomic indices and ecological deposits and withdrawals. The growth of production and consumption overwhelms the forward steps of industrial greening with the backward steps of aggregate impact of humans on the global ecosystem.2

Social scientists cannot predict the state of future society, but we can extrapolate on trends. Under the more pessimistic scenarios that examine global conditions in a future seventh generation, economic growth will continue, technological innovation will enable new forms of environmental degradation, regulation will fail to keep pace with environmental damage, conversion to renewable energy will be too little and too late, resource wars and terrorism will proliferate, civil liberties will continue to erode, cancer incidence will continue to climb, climate change will severely impact all societies, and the wealthy will pay an increasingly steep price for the “inverted quarantine” of access to clean air, water, and food, not to mention the security of life in gated communities and cloistered workplaces. The prospect of general civilizational collapse may not necessarily come to pass, but under the pessimistic scenarios there are likely to be increasingly large areas of the world characterized by slums, political chaos, starvation, epidemics, warfare, and genocide.3

If ongoing growth in consumption and environmental degradation are likely to continue to outpace ecologically oriented technological innovation, then the central political and economic issue in any discussion of sustainability is the transformation of an economic system based on ongoing growth in resource use. At the heart of that system is an amoral financial system that structures the goals of the publicly traded corporation around revenue and earnings growth. Advocates of eco-innovation argue that the self-correcting mechanisms of the market will generate increasing investments in green technologies, and there is some evidence that firms have shifted to practices that lessen their ecological footprints while also finding new sources of profit. However, studies of the greening of industry suggest that the primary causal factor behind eco-innovation is regulatory push rather than profitability pull. Even while some large, publicly traded corporations are making environmentally significant changes in their products and production processes, other corporations are finding new ways to exploit the environment.4

If the market alone cannot solve the problem, government policy is needed. However, the government, like the market, is likely to fail at providing adequate technological and economic change in a timely manner. Since the 1970s the trend has been for governments to adopt neoliberal policies in support of increased privatization, as Pincetl and Porse described in Chapter 4, and of decreased government regulation. As a result, the potential for many governments to steer the economy in a more sustainable direction is weak. Even where there is little overt hostility to the fundamental proposition that some environmental regulation is needed, the regulatory interventions of most nation-states and international treaties have been inadequate to reverse ecological crises such as climate change, ongoing habitat destruction, and pervasive chemical pollution. Furthermore, some international agreements have significantly reduced the capacity for national and subnational governments to develop environmental regulations.

If one accepts the two basic arguments—that the publicly traded corporation has a growth logic that is at odds with significant restoration of ecological balance, and that neither the self-correcting mechanisms of the market nor the regulatory push of the nation-state have to date generated an adequate response—then one is left with little hope for significant change led by industrial and political elites. Although they are responding to environmental change by sanctioning a greening process, their responses have been inadequate to address the crisis. Given the absence of adequate leadership from elites, grassroots efforts have played and continue to play a role in generating the political will to make more significant reforms. Although social movements often lack the power to have a transformative effect on society, they can, at some historical junctures, raise effective challenges to the legitimacy of the dominant institutions, and as a result the action of social movements can lead to some changes. The extent to which those changes can be of great enough significance to reverse the flow of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere and toxic chemicals into the biosphere is impossible to determine. However, an analysis of the diversity, trajectories, and impacts of those movements may provide some insight into how they can be made more effective.

A typology of sustainability movements

The social movement literature, especially as it has developed in the English-speaking countries, is rich and complex, but in some ways it is also too narrowly focused for the study of sustainability politics. For example, it is too easy to circumscribe prematurely the object of study, the social movement, and to exclude from the horizon of analysis other forms of action aimed at societal change, especially the role of innovation that appears in the nonprofit sector, informal community networks, entrepreneurial businesses, charitable activities, and hobbies. A broader category of action is needed. Some of the leading social movement theorists have recognized the problem and suggested the term “contentious politics,” but not all of the action that will be discussed here is recognizably politics, and not all of it is contentious. As a result, I use “alternative pathways” as a general umbrella term for the wide range of sustainability-related movements to be discussed here.5

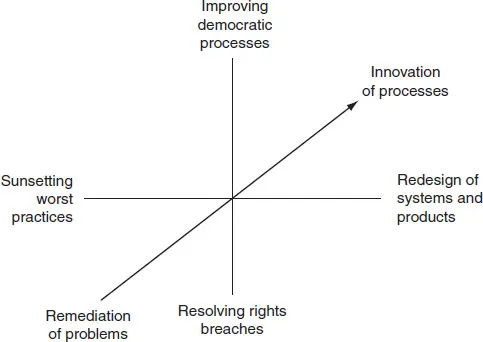

Sustainability is understood here as a political value that is situated in a contested field of action that can be conceptualized as having an environmental and social axis (see Figure 13.1). Along the environmental axis there is a range of possible positions, from remedial approaches such as sunsetting worst practices to radical technological innovation such as the redesign of product life cycles, as occurs in the zero waste and industrial ecology fields. Likewise, along the social axis there is a parallel range of possible positions, from remedial approaches that correct lapses in human rights such as exposure of low-income communities to toxic chemicals to more process-oriented approaches that focus on making political and economic institutions more democratic, participatory, and deliberative. Together, the two axes form a field of potential and existing change action that would move society toward a state of “just sustainability,” that is, a society that has not only solved its worst abuses of environmental and human degradation but has designed new technologies and institutions that would solve the environmental crises in a democratic way. Notice that in this conceptualization the “economic” is not a third axis, but instead a means toward achieving the value of a justly sustainable society.6

Figure 13.1 Sustainability as a field of contestation (source: Hess, 2007a).

Business and government elites tend to define the politics of sustainability in a reductionist way. First, they often ignore the connection between environmental sustainability and social justice so that sustainability becomes a one-dimensional environmental issue defined by the greening of industrial processes, and second, they tend to define the environmental problem in terms of remediation rather than the fundamental rethinking of technological design and economic organizations. From the minimalist perspective of the elites, sustainability tends to be defined in terms of sunsetting various worst practices, such as immediately threatening pesticides, particulate emissions from diesel engines, or high levels of carbon dioxide. The project of transitioning to new socio-technical systems—a chemical industry freed from organochlorines or a transportation sector powered by renewable energy—is often relegated to long-term research. By making sunsetting the short-term goal and redesign the long-term goal, the prospect of building a sustainable society is deferred to some future time, and short-term profits are left unthreatened. In contrast, the wide range of social movements and other types of social change action help keep alive a broader vision of building a more just and sustainable society.

To get some handle on the wide range of movements related to the broad vision of sustainability, I have developed an analytical scheme that allows some comparison across the historical instances of social change action oriented toward justice and/or environmental sustainability. “Civil society” is understood as the third sector of organizations outside the for-profit and public sectors. Within civil society there will be a focus on “movements.” A social movement has broad scope in terms of organizational diversity and temporal duration; an intention to change society from below, that is, by groups that are not part of the ruling elites; and repertoires of action that include extra-institutional strategies such as protest. When the effort to change society occurs within an industry or a profession and utilizes institutionalized repertoires of action, I use the term industrial or professional “reform movement.” When the scope is smaller than a movement, I use “activist” for groups that use extrainstitutional protest and “advocates” for those who work more within the system. The term “interest group” is reserved for groups that do not seek to change society but instead hope to gain resources for a specific segment of society.

The terms serve as guideposts for under...