![]()

Part One:

Facing the Challenges

![]()

| | |

| 1 | | The First Challenge: Rebalancing Our Urban Economies |

The first challenge is one first posed by Ebenezer Howard in his famous diagram of the Three Magnets, in 1898: The People: Where will They Go? It has lost none of its potency in the intervening century. Indeed, it is more urgent and more relevant than ever. For the underlying question is: The People: Where will They Work? It has become ever more evident, ever since the 1930s, that the British economy is suffering from a chronic problem of regional imbalance. It is often, but inadequately, labelled the North-South Divide. During the immediate postwar period, from 1950 to 1970, this problem was temporarily obscured by a burst of economic growth that appeared to be lifting the industrial areas of the North and Midlands out of the deep structural depression that had afflicted them in the 1930s. But then, rather like a malignant cancer that aggressively reasserts itself the disease reappeared, now affecting regions, like the West Midlands, that had been hitherto thought immune. Deepening through the 1990s and 2000s, appearing in stark form in the global economic crisis of 2007–2008, it is now effectively dividing the United Kingdom into two starkly contrasted nations: a small urban island plus a few privileged subsidiaries, and a vast urban territory that has lost the capacity to cam its living. Understanding its nature and its causes is the basic key to any solution.

The deep trends that are affecting the British economy, and its constituent towns and regions, arc well-enough known:

♦ the shift from a residual manufacturing sector to advanced producer services (not just financial ones) as the economic driver;

♦ skill shortages in high-level science and engineering and in middle-range technology, and a surplus of under-qualified workers, requiring a major drive to educate and retrain the workforce.

The North-South Divide; and the Great Cities versus the Rest

In consequence there is a new geography of England: the old North-South divide remains, but is overlaid by a distinction between the major cities and the rest. London and South East England are successfully making the transition to the knowledge economy, but there are big differences even there, between the successful towns and the sleepier rural hinterlands. In the North, the Core Cities1 are increasingly polarized internally, with successful centres and university quarters contrasted with deprived middle-city rings and outer-ring estates; outside them, many former one-industry towns (including towns whose single industry was seaside holidays) arc proving much less successful in forging the transition into the knowledge economy; farther out in wide-ranging attractive rural areas, small country towns are flourishing as commuters and retirees bring their incomes with them from the cities.

The Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change at the University

Figure 1.1. The North-South divide. (Source: http://sasi.group.shef.ac.uk/maps/nsdivide/ns_line_detail.html)

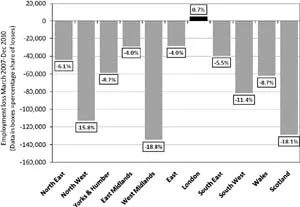

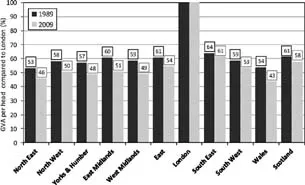

of Manchester (CRESC) show that in the 2007–2010 period of recession, some 712,500 jobs were lost nationally, but more than 85 per cent of these, a total of 621,200, were lost in the ex-industrial regions of the West and North, notably in the West Midlands, Wales and Scotland (figure 1.2). CRESC argue that London has in effect become a new version of the medieval city-state like Florence, essentially autonomous and pursuing its own ends which may be at variance with those of the rest of the country — a view increasingly echoed in many media commentaries: ‘There is a case now, financial, social and ethnic, for treating London as a separate island within England rather than as a part of it. There is no dimension of life in which London is typical of the nation of which it is the capital city and centrifugal force’ (Collins, 2013, p. 29). This is illustrated by longer-term changes in regional Gross Value Added (GVA) per head, where every region — even the South East — has declined in relation to London (figure 1.3) (Ertürk et al., 2011; cf. Heseltine, 2012, chart 1.11, p. 26).

Figure 1.2. Regional share of total UK job losses, 2007–2010. (Source: Ertürk et al., 2011, p. 4)

Figure 1.3. Regional GVA per head compared to London, 1989 and 2009 (as a percentage of London). (Source: Ertürk et al., 2011, p. 10)

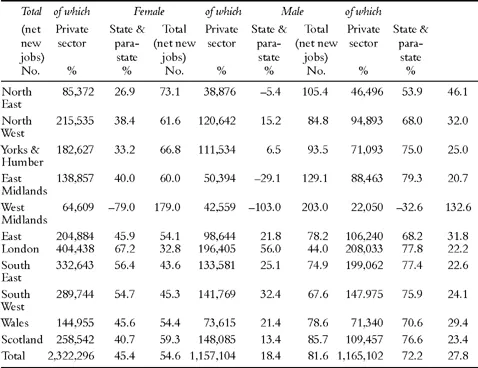

A further critically-important piece of this story is that these peripheral regions have become increasingly dependent on state employment plus what CRESC calls the para-state sector — that is, publicly-funded but privately-employed workers, the numbers of which CRESC has been able to estimate for

Table 1.1. Regional employment change in the state and para-state sectors, 1998–2008.

Note: The table is a measure of employees not jobs (where an employee can have more than one job).

Source: Ertürk et al., 2011, p. 11 and Nomis (www.nomisweb.co.uk).

the first time (Buchanan et al., 2009). Figure 1.3 shows that while in London these two classes of worker accounted for only 32.8 per cent of job growth between 1998 and 2008, in the North West the proportion rose to 61.6 per cent, in Yorks and Humber to 66.8 per cent and in the North East to 73.1 per cent. In the West Midlands, the extreme case, they provided the sole growth since private employment declined.

CRESC argue that from the 1980s — when deindustrialization had already destroyed much of the traditional employment base of the midland and northern regions — Thatcherite and subsequently New Labour governments effectively made a kind of Faustian bargain, allowing the finance-driven London economy freedom to expand, while providing massive subsidy to the other regions either by way of social services universally available in all regions, or by state or quasi-state new jobs (many of which provide the services), or by generously subsidizing the long-term unemployed through incapacity benefits: what the CRESC researchers call ‘a new Speenhamland which offered full maintenance for a wholly unemployed industrial population’ (Ertürk et al., 2011, p. 29).2 As the CRESC report puts it, ‘in the absence of any other signs of economic life in the deindustrialising regions, these universal provisions became a de facto regional policy’ (Ibid., p. 30). But, in the crisis that began in 2007, this has come to a sudden halt as both are suffering from public expenditure cuts.

True, prosperous southern cities like Oxford and Cambridge show the highest dependence of all — but much of this is in sophisticated R&D, well supported by national and international funds. In contrast public sector employment in Hastings (42.2 per cent), Belfast (40.7 per cent), Swansea (38.5 per cent), Dundee (37.3 per cent) and Liverpool (36.0 per cent) is much more vulnerable to public expenditure cuts — and, apart from Hastings, these places are heavily clustered in the north of England and the Celtic peripheries (Larkin, 2009).

This in turn is related to another key indicator: the UK labour force generally is underskilled, and this deficit is worse in the northern cities. Unsurprisingly, therefore, these cities still have major concentrations of deprived households. The consolation is that between 2004 and 2007 they improved. But other, smaller, northern places deteriorated. In fact, if there is one striking contrast between northern and southern England, it is found in the medium-sized towns: in the south, these places — typically county market towns with a strong service component like Reading, Maidstone, Oxford and Cambridge — have gone from strength to strength, while their northern equivalents — typically one-industry towns that have lost their former economic base — have steadily sunk.

Beyond the North-South Divide: A New Geography of Britain

To characterize this emerging post-industrial geography simply as a north-south divide is too crude, though that divide — first recognized in the great depression of the early 1930s — is an important element in it. Rather, at the risk of some simplification, it can be described in terms of a four-fold taxonomy:

1. The South East Mega-City Region: a vast complex comprising London and its commuter catchment area, plus fifty separate cities and towns, all medium-sized or small, and their catchment areas, stretching as far as 180 kilometres from central London, and in course of permanent enlargement.

2. The Rural Periphery of Southern England: a vast penumbra to the first region, stretching out through extensive rural areas as far as the North Sea on one hand, the Atlantic Ocean on the other, and embracing much of Wales.

3. The Archipelago Economy of Midland and Northern England, characterized by a relatively few Core Cities that have suffered from major deindustrialization but are now in course of slow transition to the service-based knowledge economy, surrounded by wide rings of ex-industrial towns that are having much greater difficulty in achieving this transition.

4. The Rural North: the wide intervening areas of northern England, separating the Core Cities and their surrounding regions, and stretching far out across thinly populated scenic areas, much of which are protected National Parks, as far as the west and east coasts.

Over the half-century or so since 1960, these four regions have experienced very different trajectories in terms of economic change, migration and consequent demographic evolution, and social change. But they are in course of constant dynamic evolution, and some individual sub-regions of the country can be said to be transiting from one to another. So their fortunes may change from decade to decade, sometimes at bewildering speed.

The South East Mega-City Region

South East England is an example of a new spatial scale: the Mega-City Region (MCR) (Hall and Pain, 2006). Originating in the 1990s in Eastern Asia, where it was applied to areas like the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta regions of China (Lin and Ma, 1994; McGee, 1995; Sit and Yang, 1997; Hall, 1999; Scott, 2001; Wo-Lap, 2002, quoted in UN-Habitat, 2004, p. 63), it is essentially a new form: in the South East England example, some fifty Functional Urban Regions (FURs), around a major central city, physically separate but functionally networked, and drawing economic strength from a new functional division of labour. These places exist both as separate entities, in which most residents work locally and most workers are local residents, and also as parts of a wider functional urban region connected by dense flows of people and information along motorways, high-speed rail lines and telecommunications cables. It is no exaggeration to say that this was the emerging urban form at the start of the twenty-first century.

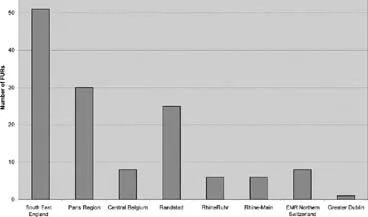

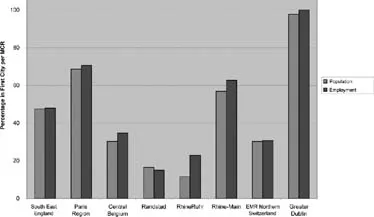

A recent study of eight such MCRs in North West Europe3 (Hall and Pain, 2006) found that South East England is the largest of these regions in terms of population, with 18,560,000 people in an area of 27,332 km2: one-fifth of the land area of England with nearly two-fifths of its population. It is also the most complex, with no less than fifty-one constituent FURs including London itself (figure 1.4). It consists of London and its immediate commuter catchment, stretching approximately 40 km from central London, together with fifty other cities and towns and their individual catchments, ranging in population from 600,000 down to 80,000, and extending as far as 180 km from London. Planning controls, imposed since the 1947 Planning Act, have successfully maintained physical separation between these units, producing a pattern on the ground, and still more strikingly as seen from the air, of ‘towns against a background of open countryside’, the traditional British planning ideal first enunciated in the 1920s by Raymond Unwin. But, especially west of London, they are functionally interrelated through daily commuter exchanges and still more by exchanges of information in the course of daily business. Thus, illustrating that the region is polycentric not only in a physical but also in a functional sense (Ibid.).

Figure 1.4. Comparison of the number of FURs across eight European polycentric regions, c. 2000. (Source: Hall and Pain, 2006, p. 22)

Figure 1.5. ...