![]()

Chapter 1.

Community Markings

Acknowledge a Disconnect

Openly acknowledge any philosophic, economic or social differences between your HHM's narrative and the immediate community surrounding your site.

Rant

We discuss connecting our sites to the 'community'; however, that is such a nebulous term, which means different things to different people. Historic houses can no longer just cater to the stereotypical visitors of the past, upper middle class white people with advanced degrees who walk in with vast amounts of prior knowledge. Many of our houses are in areas surrounded by 'non-traditional' audiences; we should be asking first and foremost how to be relevant to them. What can our house do for them?

(Carol Ward, Executive Director, MorrisJumel Mansion)

Evidence

HHMs can be culturally elite and removed. Most are unintentionally off-putting and expect the community to be naturally interested in them. How do we know this? We asked. Most people we engaged with our mobile kiosks told us they had never heard of our Historic House Museums, and if they had, they didn't know that the HHMs were open to the public. More importantly, the stories the historic sites offered did not seem to resonate as currently meaningful. In fact, HHMs have a reputation for showing little interest in the neighborhood that surrounds them. In calling for museums to reconsider their underlying purpose, meaning and value, Robert Janes wrote:

Museums have led a privileged existence as agenda-free and respected custodians of mainstream cultural values.... Museums are privileged because they are organizations whose purpose is their meaning.... The failure to ask 'why' museums do what they do discourages critical self-reflection, which is a prerequisite to heightened awareness, organizational alignment and social relevance. Instead, in the absence of 'why,' the focus is largely on 'how,' or the cliched process of collecting, preserving and earning revenue.1

Being relevant requires finding common ground. As neighborhoods surrounding HHMs change and evolve, the HHM typically stays the same, taking on the noble responsibility for relaying the story, or at least their version of what once was. They usually care little to update the HHM's narrative to reflect current events. But the telling of history is nuanced, and what is included, or conversely excluded, speaks to HHMs' willingness to acknowledge its shifting context.

Maybe what House Museums offer is not what the community wants. As Americans become increasingly connected, they are also searching for meaning in their lives and their place in the community Many people, especially Millennials, claim that they want their work to be transformative and help people, not institutions, and support issues, not organizations.2 HHMs rarely offer those kinds of opportunities. Douglas Worts writes, cultural organizations are likely to hold tight to their traditional modus operandi, at least until they see that the potential rewards are higher than preserving existing corporate operations.3

As the Center for the Future of Museums (CFM) noted in 2009: "As the nation becomes more diverse, and as the gap between wealthy and poor (even middle-class) Americans grows, museums will have to expand their audiences if they want to remain relevant to society as a whole."4 Yet we now recognize "how little we actually know about populations who, for a variety of social, cultural, and economic reasons, do not yet enjoy regular access to museums. It has become increasingly clear that most existing evaluation and research studies are not representative of the overall population in the United States."5

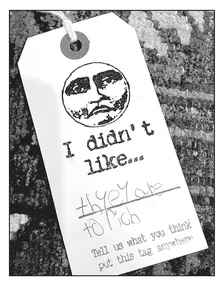

Figure 1.1: Reflective of a social and class disconnect, this Anarchist Tag from a seventh grade New York City school group student visiting Morris Jumel Mansion in Manhattan, NY, states, "I didn't like...they are too rich." Anarchist Tag pilot project facilitated by Carol Ward, Executive Director, and Danielle Hodes, Director of Education, at the Morris Jumel Mansion. Photo:Franklin Vagnone, 2014.

"There are organizations dedicated to better understanding the populations that do not regularly attend museums. One such organization is Cool Culture. Founded in 1999, its mission is to "combat barriers to access—such as high admission fees during regular business hours, lack of information, and deep-seated social differences along class, language, and ethnic lines—while simultaneously educating parents about the positive impact museum-going can have on their child's overall development and success."6 Their long-term wish is to open the traditionally elitist world of cultural organizations and museums to a much wider audience.

If HHMs remain out of touch with diverse audiences, it may be due to their insistence on adhering to old museum models. HHMs began in an effort to establish national identity. Little by little, however, conversations that question the validity of one unified national identity are positively infiltrating the Historic House Museum landscape. In December 2014, President Obama signed a law to establish a national historical park at the former home of Harriet Tubman in Auburn, New York. It is the first national historical park named for an African-American woman, an important step towards a more inclusive national identity.7

One of the interesting trends in cultural happenings is 'guerilla art' instigated as a form of social advocacy. For example, in post-recession Detroit, where tens of thousands of abandoned and blighted homes and buildings dominate the city's urban neighborhoods, Tyree Guyton and the Heidelberg Project have reimagined the domestic world of Historic Houses. Using abandoned houses and cars in the neighborhood where he grew up as his canvas, Guyton uses discarded materials like record albums, bicycles, vacuums, shoe, dolls, and stuffed animals to create whimsical pieces. The purpose and meaning of the work is clear: as Guyton writes, "If I can do just one small thing to help this community come back then I've done my job."8 His goal is not so much about preserving a collection, or a moment in time, but rather about connecting people.

Therefore

Stop expecting people to be interested in what you have been offering. Be willing to re-think the types and methodologies that shape your visitor's experience and ensure that it is both socially relevant to your surrounding neighborhood and personally compelling. In addressing a cultural disconnect, provide opportunities to build community by doing good. Make sure that understanding your community is a top priority.

Refocus Your Mission: Have an Impact

Allow the needs of your immediate community to modify your mission, goals, focus and strategy

Rant

When I am working with a historic house museum, or really any type of museum, I get confusing signals. I always want to ask, 'What business are you in?' Some museums seem to be in the business of 'preserving artifacts/leaving little room for interpretation and telling stories. Others seem to be in the business of 'creating narratives,' and yet their stories can be internally focused. I'm always looking for examples of museums that are in the business of 'engaging communities'... whether visitors, scholars, donors, or those who live and work nearby. This focus on people rather than things, and living people, not just the people of the past, can be the spark that will keep museums relevant today and in the future.

(Ro King, Trustee, The Menokin Foundation, and Chairman Emerita, Indonesian Heritage Society)

Evidence

Most HHMs consider the protection, stewardship, and enhancement of their collections as their primary mission. Few Houses focus on how to make their assets useful for, meaningful to, or have an impact on the community. In our research, we repeatedly found only a handful of sites that made substantial civic engagement a priority. Clearly, this is not a strong area for our museum genre.

In the early 1900s, museum leader John Cotton Dana wrote that "a museum's main objective was to be relevant to citizens' daily lives and promote lifelong learning and civic engagement."9 Lynn Dierking agreed, writing that museums should "strive to achieve strategic impact for and with their communities, rather than merely operational impact for themselves."10 Similarly, our hope for HHMs is that they be more than repositories of historical artifacts and information, that they be engines capable of having a positive impact on the community that surrounds them. Adopting this perspective will require a philosophical shift in thinking for most HHMs, so we underscore it as one of the fundamental components of the Anarchist's Guide.

For many HHMs, it will initially be difficult to find "a place of relevance and meaning, to genuinely contribute to building better communities and serving the needs of individuals, and to define the new normal in a world that no longer derives knowledge from objects, looks to institutions for answers, or defines reality through materiality."11 But it is possible.

A few House Museums are having a substantive impact (outside of normative House Museum practice) in their communities. Examples include the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum in Chicago with their heirloom urban farm and "Re-thinking soup" event; The Lower East Side Tenement Museum, New York, with their English as a second language classes; Hancock Shaker Village with their community-supported organic farm and market; Fort Snelling in St. Paul with their "sentencing through service" job training for inmates; Lewis H. Latimer in Flushing, New York, and The Stowe House in Hartford, Connecticut, with their social justice salons, and King Manor Museum and Old Stone House in New York City with their facilitating Naturalization Ceremonies.

One visually stunning example of this outward-focusing perspective was a 2013 exhibition entitled LAND/SLIDE: Possible Futures at the 25-acre Markham Historical Village in Ontario, Canada. Over 30 artists created site-specific contemporary installations, many of which grew out of contentious community conversations about development pressures on rural land and the value of history in the contemporary landscape. The exhibition was an attempt to expand the traditional Historic House narrative to include current community issues and employ the region's history as a means to discussing its future.12

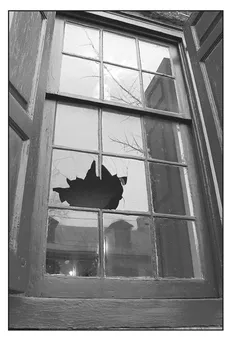

Figure 1.2: Grumblethorpe Historic House Museums in the Germantown area of Philadelphia, PA. In 2006 a brick was thrown through the street-front window, perhaps, at least in part, due to a neighbor's indifference to the HHM's isolation. The vandalism sparked a re-assessment of the House's relationship with the community and the establishment of the Grumblethorpe Farm Stand which was managed by the neighborhood-based Grumblethorpe Youth Volunteers. The project was facilitated by Brandi Levine, the then education director, and the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks. Photo: Franklin Vagnone.

Another example is Grumblethorpe (c. 1744), a HHM located in in the Germantown section of Northern Philadelphia. In 2006, when we first became involved with the HHM, a brick bad just been thrown through one of the front parlor windows. At the time, the HHM had very low walk-in visitorship. There was a strong youth volunteer group who helped give tours, but not much else was occurring that contributed to the community's needs. One of the most pressing issues was that the neighborhood was a food desert, defined as a place that lacks easy access to fresh food. Residents had to rely on convenience stores, where they had very limited choices. To contribute to a solution, Grumblethorpe's Education Director Brandi Levine managed the replacement of the formal, colonial revival gardens with a vegetable garden that provided a source of fresh food to the neighborhood, while also starting a new program to manage the produce with the established youth volunteer program.

The Grumblethorpe Farm Stand immediately became a welcomed addition to the neighborhood. It attracted the interest and patronage of the entire surrounding community. It also showed that we were paying attention to the real world problem of this underserved neighborhood and how the history of the site could contribute to a healthier community. The farm stand continues today because it is an important contributor to the food sources in this neighborhood.13

The Heritage Square Museum in Los ...