eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

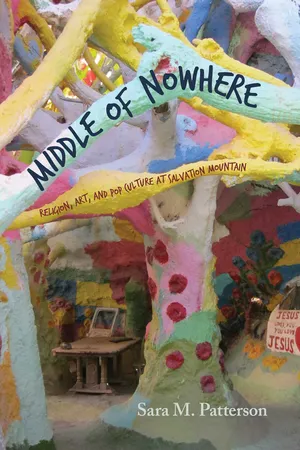

Middle of Nowhere

Religion, Art, and Pop Culture at Salvation Mountain

This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Pilgrims travel thousands of miles to visit Salvation Mountain, a unique religious structure in the Southern California desert. Built by Leonard Knight (1931–2014), variously described as a modern-day prophet and an outsider artist, Salvation Mountain offers a message of divine love for humanity. In Middle of Nowhere Sara M. Patterson argues that Knight was a spiritual descendant of the early Christian desert ascetics who escaped to the desert in order to experience God more fully. Like his early Christian predecessors, Knight received visitors from all over the world who were seeking his wisdom. In Knight’s wisdom they found a critique of capitalism, a challenge to religious divisions, and a celebration of the common person. Recounting the pilgrims’ stories, Middle of Nowhere examines how Knight and the pilgrims constructed a sacred space, one that is now crumbling since the death of its creator.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Middle of Nowhere by Sara M. Patterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Outsiders All

Art, Religion, and Sacred Space

Some of us aren’t meant to belong.

Some of us have to turn the world upside down and

shake the hell out of it until we make our own place in it.

Some of us have to turn the world upside down and

shake the hell out of it until we make our own place in it.

EVEN THOUGH LEONARD KNIGHT’S religious conversion was profoundly shaped by the churches that he visited, and even though his born-again identity became central to who he was, during his time at Salvation Mountain, Knight refused to attend any church. For over three decades he did not go to church because he didn’t want to “love Jesus secondhand.”

This wasn’t an easy choice. Knight’s refusal hinged on his frustration with the separations he saw in Christianity. He believed that bigger churches lorded their numbers over other Christians, claiming, “I’m the biggest there is.” Those churches, Knight thought, should be rebuked for excluding other people: “Hey, you be careful with God, because he loves everybody in the whole world. Everybody he ever made. Don’t go around thinking things like that.” Knight was concerned not only with big churches but also with the pastors who earned degrees and emphasized doctrine over the biblical text. “I don’t care if it’s the biggest church going, if they’ve got four master’s degrees and they make a silo full of money every day. That is not interesting,” Knight claimed. And he believed that those same church leaders picked on him “because I’m a dumb dropout from high school in the tenth grade.”

Knight argued that church divisions were rooted in human debates that divided rather than united God’s people. In the midst of the arguments about orthodoxy, he claimed that Jesus was left out. Instead he wanted “100% Jesus and God . . . 100%.” Knight’s view on the church as an institution was clear: “It’s a complicated mess, if you want the truth. I wish somebody could put that in a nice way. Don’t get so complicated. Keep it simple. God loves us all. Next question?”

When I first asked Knight if he called himself a Christian, he replied, “No, I call myself . . . I don’t call [myself]. . . . There are ten thousand people out there calling themselves Christians and they are all fighting each other and biting and fighting and bickering. So I don’t want to get mixed up in too many complicated things.” Later, he explained that he was a Christian, but not like the Christians he had just described, the kind he believed populated the pews of churches around the world. He wanted to stand outside the church in order to call its bluff. He wanted to coax the church back to what he believed true Christianity was—gratitude for God’s love. Knight saw corruption, an emphasis on material wealth, and orthodox doctrines as that which made things “too complicated.” His keep-it-simple approach put him outside the church; he refused to attend even on Sunday mornings.

Much of Knight’s life was spent as an outsider. While his Christian identity was key to who he was, he refused to associate himself with any group within the Christian community—to the extent that he hesitated to call himself a Christian because the term itself might conjure up in people’s minds a different vision of the world than he imagined. At the same time that Knight purposefully stood outside the church walls, he also stood on the periphery of the art world that came to celebrate his work in the last decade or two of his life. Knight’s life’s work was a piece of art, and yet he never felt kinship with the art world. Indeed, he was flattered by critics suggesting that he was a notable artist but remained concerned that someone might think of him as an artist rather than a follower of Jesus.

It was a spatial move that truly unmoored Knight and allowed him the distance to both critique and embrace the church and the art world. That spatial distance fostered a sense of self in relationship to the Christian community and to the art world. Knight embraced his position as an outsider. At times that outsider identity was foisted on him by others and then embraced by him, and at other times he chose the outsider identity, exercising his freedom to decide who he would be in relationship to his culture. Knight’s spatial distance allowed him to create a distinct outsider identity, one that later reinforced his standing in his community as a prophet and enhanced his ability to create sacred space.

OUTSIDER ART

Many call Knight’s work “outsider art,” a term used in the art world to designate the work of a broad category of untrained artists who do not follow the dictates set forth by educational institutions and museums. Basically, the term is applied by art scholars to those who haven’t been trained as they (and the artists they know) are. In 1945 European artist Jean Dubuffet coined the term “Art Brut” (Raw Art) to “describe works created outside the art world and . . . interpreted . . . as rejecting the mainstream aesthetic.” Believing that the term was “too French,” British scholar Roger Cardinal employed the term “outsider art” in 1972 to describe artwork that stands outside the mainstream, embodies imagination, and explores “the psychic elsewhere.” More recently in the United States, the term has been tied to the artist’s identity, the aesthetic sensibility of the work, and the contexts and meaning of the artwork.1

In scholarly communities discussions of outsider art run even deeper. John Maizels, one of many scholars who study outsider art, expresses these sentiments when he describes it as “the extreme expressions of those outside society’s influences . . . uniquely original creations that stem from the inner psyche. . . . They are . . . a compulsive flow of creative force that satiates some inner need.”2 According to such scholars, outsider artists manage to stand outside their cultures and are driven solely by internal influences. Journalist Greg Bottoms echoes these ideas by claiming that outsider art “is not fueled by aesthetic concerns, at least not primarily.” Rather, he suggests, it is fueled by “passion, troubled psychology, extreme ideology, faith, despair, and the desperate need to be heard and seen that comes with cultural marginalization and mental unease.”3

Several assumptions underlie these definitions. First, the very term “outsider art” implies something about how we understand taste and artwork. It exposes that we assume knowledge and education are strongly correlated to competence and talent: the more training and the more credentials, the more ability, we think. Outsider artists break through these expectations; they demonstrate that there is not a direct correlation between education and artistic endeavor or merit. They are noticed and discussed as being competent without being trained, and that becomes the defining trait of their artwork precisely because it goes against people’s expectations.4 In this discourse, outsider artists are portrayed as exceptions to the rules rather than challenges to the assumptions within the rules.

Understandings about outsider artists also expose our assumptions about what might drive the artists themselves. Art critics assume that untrained individuals must be driven by some sort of mental illness, religious passion, or some other set of “extreme” emotions. These suppositions are highly problematic. First, they define these artists as “other.” Second, they suggest that trained artists are never driven by intense emotions, mental illnesses, or religious passion. Critics imply that these artists are outside of the norm, that they are not like “us.” In these definitions, art becomes an antidote to some form of insanity that can serve the same function as “endless bottles of tranquilizers and psychotropic drugs.”5

Though Knight’s work has been included in several art collections of outsider art, those collections tend to pay little attention to the religious aspects of the work. Most works on outsider art seem uncomfortable with the topic of religion unless it is read as a cause of fanaticism and therefore a reason to “other” the artist. John Beardsley, who has described such religious art as “visionary art,” explains that for religious artists, the artwork is linked to the experience of being born again and cannot be separated from its religious underpinnings.6 Leonard Knight would agree; he knew that he was called an outsider artist and had mixed feelings about it: “A lot of people call it outsider art. They talk about that, but if they didn’t talk about God almighty in there, I’d get sick.”7 Here Knight showed that religion was his primary motivation. Even so, we need not then conclude, as some art critics have, that his religious motivations were out of the ordinary or tied to some sort of psychosis. Rather, Knight was an artist driven by many complex motivations, both conscious and not, just as other artists are.

Because of his religious ideas and singular vision, Knight has been most frequently likened to two other artists. The first is Howard Finster, another artist driven by the desire to express his religious faith. Both men felt a divine call to create and both saw the attention to their artwork as evidence of divine support. Yet the primary difference between the two is that Knight (and those who knew him) never commercialized his endeavor. His art was never for sale, and he often claimed the ultimate ownership of the mountain lay in God’s hands. In this way, Knight is very much like Simon Rodia, the second artist to whom he is often compared, who never sold his work but dedicated years of his life to his project. Rodia’s Watts Towers in Los Angeles show a singularity of vision as well as sustained work on one piece of art.

The category of outsider art is itself problematic. It is a category too broad to connect its occupants except by suggesting that they are not the “us” of the art world. It is also a category that lumps together mental illness and religious passion, suggesting that the two are rooted in the same cause, neither one of which is normal. The category implies that the “us” of the art world are not motivated by these baser problems and passions but by some higher cause. The category creates class systems within the art world.

Knight’s own experiences challenge these designations. He did not want to be remembered solely as an artist, with his religious calling sidelined. He wanted a both-and world. He was an artist and he was religious. His religion motivated him to create, most certainly, but that motivation transformed him from a wanderer to an artist with a home and a place in the world. It made him understand who he was. Leonard Knight’s art made Leonard Knight, and Knight’s art created a sacred space. Indeed, Knight existed outside of the highbrow art world. He never attempted to join that crowd. His distance from highbrow art was simply a result of the tastes defined by that world. Leonard Knight was an outsider and an artist, perhaps in that way he participated in the making of outsider art.

The Watts Towers in Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of David A. Sanchez.

OUTSIDER RELIGION

It is only in today’s society, in which a secular progress narrative has been widely embraced, that Salvation Mountain could be interpreted frequently without reference to its religious context and content. An understanding of Knight’s theological underpinnings helps us to better understand his art, and we must engage that theology to truly explore his world. On the surface, Knight’s theology seems quite simple, and it is to this simplicity that many pilgrims are drawn. His message was a universal one, standing in a long tradition of the American embrace of Arminianism—a theological position that argues that Jesus’s death provided a universal salvation for all rather than an elect few, and that it is in the hands of the believer to accept or reject God’s gift of salvation.

Even though Knight’s theology was simple, it was not simplistic. We must turn to his artwork to better understand how his simple theology actually had many complex components. The largest letters on the mountain proclaim that “God Is Love.” This statement, more than any other, encompasses the whole of Knight’s theology. Knight described it this way: “I love everybody. . . . The major purpose of the whole thing is that God is giving his love to the world in a simple fashion. God loves everybody. It’s just a simple, beautiful love story.”8 This sentiment is affirmed and expanded on the right side of the mountain with large letters announcing, “Love Is Universal.” For Knight, God’s love was universal yet also eminently personal. Knight believed that God loved people in their particularity and individuality. It was simultaneously a unique love and a universal love.

“God Is Love” on the face of Salvation Mountain. Photo by author.

According to Knight, God’s universal love for humanity translated into the sacrifice of Jesus. In fact, Knight interpreted Jesus’s outcry “My God, my God why have you forsaken me” (Mark 15:34 and Matthew 27:46) as evidence that “God couldn’t look on Jesus because he was beat up so bad. . . . He went to the cross for me. Unbelievable that love out there and he did that for everybody.”9 Divine love manifested in the gift of salvation available to all people. The second-largest message on the face of the mountain is one that encourages pilgrims to say Knight’s version of the sinner’s prayer, the same prayer he said the day he became a born-again Christian: “Jesus I’m a Sinner Please Come Upon My Body, And Into My Heart.” Knight’s image of Jesus was one of a man knocking at the door of the heart of every human, waiting to be let in. He claimed that the sacrifice Jesus made was for everyone and that each individual, if willing to accept the offer and let Jesus in, could receive the promise of salvation and heavenly reward.

Since the day he became born again, Knight had imagined Jesus as his closest friend. As he went about his work, Knight carried on a conversation with Jesus on a “one-to-one basis.” “I get all alone and wow—‘Jesus I love you for yesterday. Hello God, I’m your friend.’ Hours and all alone. Most people really, to be honest, most people put Jesus off day after day. . . . He’s my friend, so I talk to him a lot.”

Knight’s “keep it simple” message maintained that this theology must exist outside of any particular denomination. As stated earlier, he refused to associate himself with any denomination or, for that matter, to attend any church because, to his mind, this would have complicated the message. In this way, Knight made himself an outsider to all Christian institutions. He very intentionally stood outside in order to embrace what he believed was God’s universal message of love. On the whole, he believed churches had gotten “too educated” and “too complicated.” In the process, they had added layers and layers of doctrines and dogmas that eventually muffled and distorted the simple message of God’s love for everyone. Knight indicated that all religious institutions, including those in other faith traditions, have so corrupted God’s inclusive love that they no longer speak the truth. Knight’s message of universal divine love, he claimed, transcended the bounds of human institutions and denominations and reflected the reality of the divine—it was boundaryless.

Suggesting that the message transcended the boundaries of all the world religions, Knight’s was an inclusive Christian stance. If asked whether one must believe in Jesus in order to have legitimate faith or to participate in spreading God’s love, Knight cagily responded, “Our only job is to love everyone because God loved us first.”10 He accepted the validity of other religious traditions and did not believe that people of other traditions—Muslims, Hindus, Jews, and Buddhists—were going to hell. In fact, Knight’s theology of hell was relatively nonexistent, particularly in the last decade of his life. Knight was not concerned about people receiving some ultimate judgment in the next life but was concerned with developing and encouraging love in this one. This commitment shaped his approach to other faiths. Knight embraced Jesus as his way of finding God’s love and transforming his life. In the end, though, his concern was that others were experiencing God’s love and living that love in the world; how they got there, their faith tradition, was less important. Knight would certainly share his message about Jesus with those who wished to hear it, and with some who did not, but if they understood and felt love and God, he had no quarrel with them. He did not believe he was called to judge anyone. On this topic, Knight also intentionally stood outside of many Christian denominations that would claim that Jesus is the only path...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Outsiders All: Art, Religion, and Sacred Space

- Chapter 2 “Nowhere Else Is Like This”: The Space of the Place

- Chapter 3 Gift Giving and Mountain Making: Exchange and Sacred Space

- Chapter 4 When Prophet Meets Exile: Salvation Mountain and the Paradox of Freedom in the American West

- Chapter 5 “Up Close, It Became the World”: Pilgrimage to Salvation Mountain

- Chapter 6 “Lord Jesus, I Gave Them My Very Best”: Bad Religion, Bad Art, and the Quest for Good Taste

- Chapter 7 The Disappearance of Sacred Space? Authority and Authenticity in the Desert

- Notes

- Index