A Vast and Varied Continent

Shaping the environment for utilitarian or symbolic ends is architecture in its broadest sense. To build well involves a synthesis of optimum function, sound construction, and sensory stimulation, a formula first elaborated by the Roman architect Vitruvius about 16 BCE. Yet how these elements are combined, and the relative weight given to each, is determined by many factors: culture, economic resources, technical capacity, climatic forces, and the beliefs, values, and objectives of the builders. Of all of these influences, perhaps natural forces make the most insistent demands on a building, for it must withstand the incessant pull of gravity and the gradual attrition of weather. Yet most important and revealing, architecture, the great and silent human artifact, expresses better than any other medium the relationship the builders have with each other and with their universe— in how they place their buildings in the landscape and in the technologies they use to create a spiritually nourishing community for themselves.

Ethos, culture, technology, and climate together helped to shape the shelters and ceremonial enclosures made by the first Homo sapiens to venture into the New World. As various building types were gradually developed and refined, they paralleled the wide differences in climate and landscape found across the broad North American continent. To understand architecture in America, therefore, the landscape from which it sprang must be understood. The land in which the first Americans made their homes, the area that is now the United States, stretches 3,500 miles from the Pacific to the Atlantic Oceans and 1,200 miles from Canada to Mexico. It is a vast and fruitful land of striking geographical and climatic contrasts, far more marked in intensity and degree of contrast than the ranges to which later European settlers were accustomed in their native lands.

The Geological Features

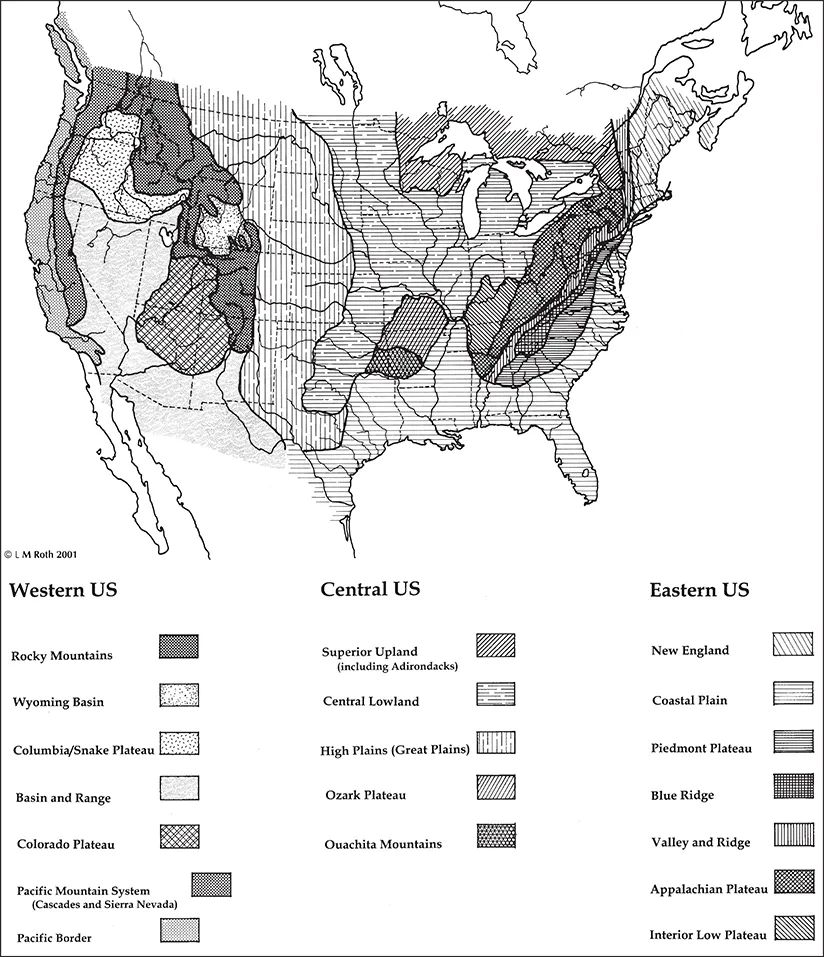

The land that became the United States was and is rich and varied, both physically and geographically, as a result of widely varied climatological regions1 [1.01]. There are three broad geographic zones across the continent: the eastern Atlantic area, the great central prairie and plains, and the western Pacific area. The eastern Atlantic area is bounded on the west by the Appalachian Mountains and extends from the Maritime Provinces of present-day Canada southwesterly for more than 1,600 miles (2,575 km) to central Alabama. This band of parallel folded low mountain ridges smooths out eastward to become the gentle hilly lowlands in the Piedmont Plateau descending to Atlantic and Gulf coast beaches. In the north, in what became New England, the lowlands are indented at the mouths of numerous rivers—the Penobscot, the Piscataqua, the Merrimack, the Charles, the Connecticut, and the Hudson, as well as the broad Narragansett Bay. In the middle of the Atlantic coast are long broad estuaries such as the mouth of the Delaware River. Just to the south opens the huge estuary of Chesapeake Bay, fed by numerous broad rivers reaching back deep into the lowlands of what would become Maryland and Virginia. South of the Chesapeake Bay begins a gentler broad and rolling landscape, made up of the piedmont that backs up against the Appalachians, and the broad coastal plain that includes most of the southern states, including present-day Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and the eastern half of Texas.

West of the Appalachians and north of the southern coastal plain is the second broad zone, the great heartland of the North American continent. Through the rolling prairies of fertile earth flow the Ohio, Tennessee, and Missouri Rivers, all of them emptying into the Mississippi (Algonquian for “Big River”), which divides the continent and carries its waters and burden of silt to the Gulf of Mexico. The westerly plains and prairies extend from Minnesota and Wisconsin southward to west Texas, and westward from Ohio to central Montana and Oklahoma to the south.

1.01. Physiographic regions and provinces of the United States, map. The large area of the United States is divided into numerous differentiated zones, especially by the three major mountain systems—the Appalachian Mountains, the Rocky Mountains, and the Pacific mountain system. (L. M. Roth, adapted from Charles B. Hunt, Natural Regions of the United States and Canada, 2nd ed. [San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1974].)

From the western high plains, the high peaks of the Rocky Mountains thrust sharply upward, marking the easterly edge of the American West the third broad zone. The Rockies form a spine of split, folded, and uplifted rock that extends from Alaska in the far north, down across the continent and south into Mexico. Immediately west of the Rockies, and further bounded to the west by other mountains, is a group of high plateaus and basins collectively called the Great Basin, or the Basin and Range. Cutting through the western-most mountains and the Great Basin are three great river systems: the Columbia River in the north, descending through Idaho, Washington, and Oregon and flowing west to the Pacific; the Colorado River, running from Colorado down through Utah and Arizona to the Gulf of California; and the Rio Grande, which extends southward from central Colorado through the center of New Mexico and forms much of the Texas-Mexico border.

The peaks of the Sierra Nevada and the isolated peaks of the volcanic Cascade Range mark the westerly edge of the third continental zone. West of those coastal mountain ranges lies the Pacific coastal region; in the northern portion, the Cascades mark the boundary between the lush green coastal zone and the brown dry area to their east.

East of the Mississippi River, the upper regions of the continent (New England and the Great Plains) were additionally shaped by the scouring of miles-thick glaciers, which repeatedly advanced and receded, pushing into the middle of the continent and then pulling back, with minor advances and retreats during the warmer interglacial ages. Like an infinitesimally slow-moving icy ocean, these glacial “waves” left behind layer upon layer of sand, gravel, clay, and soil. The great river valleys of the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi were the channels first cut by the meltwater from those ancient continental glaciers. Another gift of the glaciers was the narrow Finger Lakes in New York and the far bigger chain of the five Great Lakes. These large scoured-out basins, originally filled with glacial meltwater, now empty one into the other and eventually flow out through the St. Lawrence River and into the north Atlantic. It is sobering to think that the once-thick conifer forests of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and other northern regions—woodlands that took ten thousand years to develop after the last ice sheet retreated—were largely obliterated by only a few generations of Euro-American settlers.

The Bioclimatic Zones

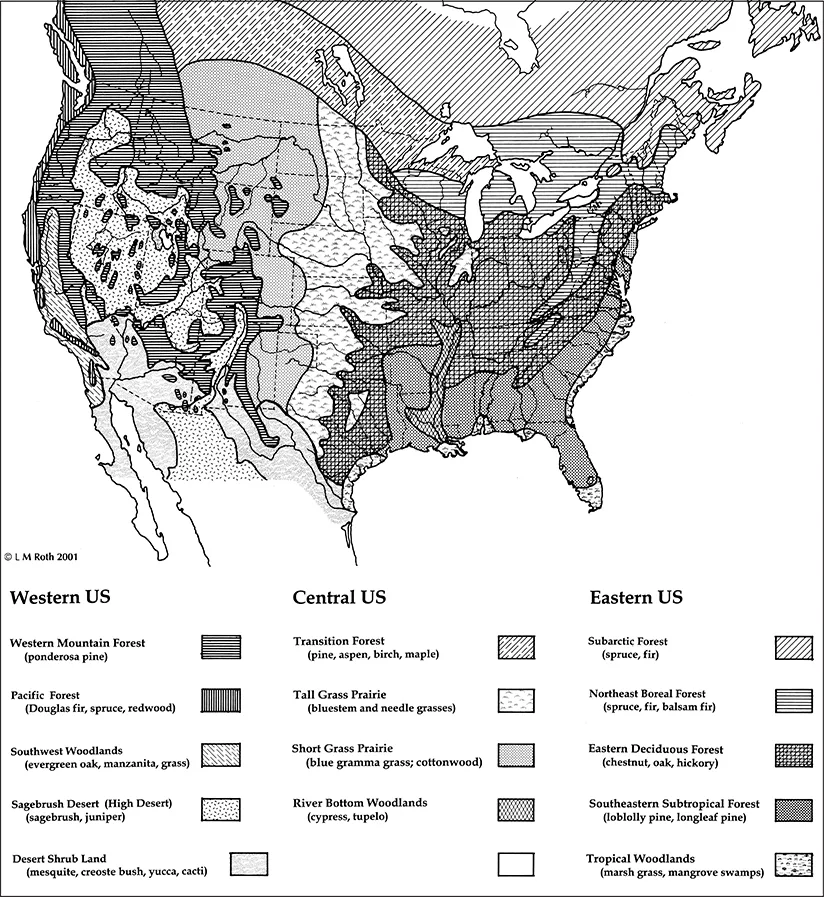

In addition to the three broad geographic zones, there are additional distinct bioclimatic zones. In the humid eastern half of the continent, these bioclimatic zones run horizontally and cut across the relatively low mountain barriers [1.02]. Well to the north, extending westward from Maine to upper Minnesota, is the northeast boreal forest, marked by thick evergreen conifer growth; here temperatures can range from an average of –4° F (–20° C) in the winter to well over 86° F (30° C) in the summer.2 In the northern forest zone, rainfall and snow tend to be moderately high, roughly 46 inches (1.2 m), which often create snow levels of 185 inches (4.7 m) in northern Michigan.

Just to the south is another, broader horizontal band that runs west through lower New England to southern Wisconsin, extending south to the Virginia piedmont and west through Missouri. In this middle latitude eastern deciduous forest of mixed conifers and deciduous trees, the temperatures are more moderate but still range over extremes much greater than those encountered in Europe, from an average low of 23° F (–5° C) in winter to more than 89° F (32° C) in summer. Although the temperatures are more moderate around the Chesapeake Bay, the humidity is much higher. In Ohio, in the midst of this zone, rainfall averages about 39 inches (0.99 m) a year.

The third horizontal band to the south is the southeastern subtropical forest, extending from the Carolinas west to Arkansas and south into the middle of the Florida peninsula. At the southern tip of Florida, below Lake Okeechobee, and in selected places along the Gulf coast, are true tropical forests of mangrove swamps. In Georgia the average inland lowest winter temperature is just above freezing, at 34° F (about 1° C), with an average summer high of about 90° F (32° C). In the tropical zone around Miami, at Florida’s southern tip, the winter average low is seldom less than 60° F (16° C), while the average summer high is approximately 91° F (33° C), accompanied by high humidity. Rainfall in this broad zone is plentiful, averaging about 53 inches (1.4 m) in central Alabama, while in southern tropical Florida it can exceed 59 inches (1.5 m) in a year.

In contrast, west of the humid eastern half of the country, the bioclimatic bands begin to align vertically and are determined more by different levels of rainfall than by comparable temperatures. The first of these vertical bands to the west occurs where the land begins its ascent to the high western plains. This transitional humid-to-arid area, originally dominated by tall grasses, extends from the Dakotas south through central Texas. Here temperatures can vary in the far north from the great extremes of –4° F (–20° C) in the winter and well over 90° F (32° C) in the summer, to the hotter climate in Texas that seldom drops below an average of 40° F (4.5° C) in the winter and easily reaches 100° F (38° C) in the summer. In this transitional band from humid to arid, rainfall varies little, from 17 inches (431 mm) a year in North Dakota to a drier 10 inches (254 mm) in some parts of Texas.

1.02. Natural vegetation zones in the United States and North America, map. The patterns of natural vegetation across the United States reveal patterns of climate so that indigenous plants are determined by latitude, altitude, and moisture as influenced by mountain barriers. (L. M. Roth, adapted from Hunt, Natural Regions of the United States and Canada.)

The next vertical band farther to the west corresponds to the high plains at the eastern base of the Rockies; this semiarid zone in the rain shadow of the Rockies extends from central Montana south to the tip of Texas, a landscape originally dominated by short grasses. In this zone, temperature extremes are equally great, ranging in northwestern Montana from average winter lows of –9° F (23° C) to highs of 76° F (24° C) in the summer, whereas in western Texas, winter lows average 33° F (1° C), while summer highs easily top 100° F (38° C). Precipitation across the entirety of this semiarid zone is extremely low, seldom exceeding 9 inches (23 cm) a year.

In the large western mountain and Great Basin area, climate varies considerably according to altitude, so that the cold higher peaks receive considerable snowfall, while the basins below remain semiarid with only sporadic thunderstorms and light dustings of snow. While more than 50 to 100 inches (1.3 to 2.5 m) of snow may collect at the mountaintops, supporting scattered portions of the western mountain forests of various pines, only seven inches (17.8 cm) of rain may reach the basin floor; scattered stunted juniper trees are sparse and sagebrush dominates in this high desert region.

Even more distinct is the southerly portion of the Great Basin; here is a true desert, forming a crescent that runs from Nevada and western Utah, down through lower California and southern Arizona, eastward through lower New Mexico and the western fringe of Texas. In this desiccated area, rainfall varies from a low of four inches in Nevada to eight inches in the four corners area, where the borders of Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado form a right angle.

Farther west, however, across the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Range, far different gentler climates prevail. Along the northern Pacific coast, from British Columbia to San Francisco, the prevailing westerly winds incessantly drive clouds up against the mountain barrier, forcing them to drop their moisture; only in the late summer does this cease. Here are found dense forests of towering Douglas fir, spruce, redwood, and sequoia. Along the coasts of Washington and Oregon, temperatures range from a winter low of 40° F (2° C) to a summer high of 77° F (25° C)—although summer temperatures in the interior valleys range about 10° F higher. Rainfall can reach 100 inches (2.5 m) in the mountains of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, but elsewhere the average is closer to 82 inches (2 m) in the peaks of the Cascades and Sierra Nevada, creating snow packs in excess of 22 feet (6.7 m) in depth.