1

CURRENT PERSPECTIVES AND NEW

DEPARTURES

The Industrial Revolution has long been a terrain of debate and controversy among economic and social historians. Debates over how much change, how fast, and what impact this had on communities and peoples have been part of the process of making the concept itself. These debates, among what have become rather specialist historians, have in turn affected our wider historical sense of identity. The Industrial Revolution has been conceived of as a period of transition, however long the period and varied its characteristics. It is a part of the ‘life story’ of the nation, conceived generally as its formative childhood and adolescence. The Industrial Revolution has been the starting point of accounts of political and social change and of the making of the modern economy. The developmental indicators and their trends, centred on the growth of national output, capital formation, demographic growth, and changes in economic and industrial structures, are known just as surely as are the weights, heights, motor skills, speech and understanding of the developing child.

Recently these indicators have been called to account. Quantitative economic historians have re-estimated their trends, and have found the gap between the performance of the expected and the real adolescence of the British economy to be too great to claim a transition even over the long period from the early eighteenth to the midnineteenth century. ‘Continuity’ has replaced ‘revolution’, bringing a loss of confidence in the stages of the life story. From the Right, Norman Stone dismissed the ‘industrial revolution’ as the conceptual relic of a few outdated early twentieth-century economists.1 From the Left, Gareth Stedman Jones described the ‘changing face of nineteenth-century Britain’ as the discovery of a continuity between eighteenth- and nineteenth-century class formations.2

QUANTITATIVE ESTIMATES: A NEW ORTHODOXY

Let us turn now to those analyses which have formed the foundation of our new times of historical doubt. During the 1980s a number of quantitative economic historians applied more sophisticated statistical techniques and incorporated research over the previous two decades to modify the quantitative indicators of output growth, wages and occupational structure. The national accounts and industrial and agricultural output estimates of Deane and Cole had, since the 1960s, provided the basic framework for patterns of economic growth over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Now these estimates were displaced and with them the historical turning points which had framed all previous historiography. Deane and Cole’s estimates had confirmed the received picture passed on by T.S.Ashton that ‘after 1782 almost every statistical series of production shows a sharp upward turn’.3 Deane and Cole found industry and commerce growing at 0.49 per cent for 1760–80, but 3.43 per cent for 1780–1801. 4

The displacement of both estimates and turning points was summarized by N.F.R.Crafts. Gathering together and commenting on earlier work by C.K.Harley, P.H.Lindert and J.G.Williamson, Crafts produced new composite output series for the economic sectors, agriculture, industry and commerce, and government and services. He also produced estimates of the growth of national product and of total factor productivity growth. These estimates are summarized in Tables 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3.

Table 1.1 Output growth, 1700–1831 (% per year)

Table 1.2 Estimates of total factor productivity growth (% per year)

Table 1.3 Revisions to estimates of industrial output growth (% per year)

New estimates provided evidence for several challenging conclusions on the patterns and structures of British industrialization. First, rates of growth of national ouput, total factor productivity, and industrial output were slow before 1830, and did not demonstrate that sharp upturn previously claimed by historians. The economy did not reach 3 per cent per year growth in real output before 1830. Real income growth was much lower than previously thought, leaving less scope for consumption to rise and less acceleration in productivity growth. Changes in investment proportions were also very gradual over the period, leaving total factor productivity growth at only 0.2 per cent per annum 1700–60, rising to only 0.35 per cent per annum in 1801–31. What increase in growth there was in the later eighteenth century was accounted for by faster growth of inputs rather than extra productivity growth. This demonstrated, contrary to all previous accounts, little effect of technical progress on productivity until well into the nineteenth century.

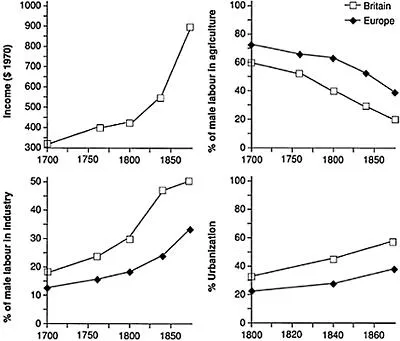

These new estimates discounted radical economic change, but they did not discount change altogether. For though growth in output and productivity were gradual they did sustain a much-increased population, and a population much more urbanized and more industrialized than either previously or in any other contemporary economy. It was in supporting a substantial proportion of this population off the land that Britain measured its achievement in comparison with other European countries.

Crafts, indeed, has described Britain as an ‘idiosyncratic industrializer’.5 Her idiosyncracy is defined by an early start on the road to industrialization, high productivity growth in agriculture which released labour to industry, but comparative advantage in exportable manufactures, especially cotton textiles. This was also a comparative advantage in goods made with relatively more unskilled labour than skilled, and it was this combined with a relatively large industrial sector and a smaller agricultural sector which set the route to later patterns of slow growth.6

It was thus the early productivity growth of and ‘release of labour’ from agriculture which, paradoxically, dictated the speed of subsequent economic growth. The problem of development faced by the British economy in the eighteenth century was not a large subsistence agricultural sector. On the contrary agricultural productivity increased steadily over the century. Crafts estimated that agricultural growth was in fact higher before 1760 than after. The first result of this was a new capacity to sustain higher populations than previously. Rates of population growth rose from -0.3 per cent in 1661 to 0.9 per cent in 1776 and up to 1.5 per cent per year in 1816.7 Customary restraints on marriage and fertility helped to create conditions for higher income levels by the eighteenth century, and ensuing population growth did not result in the ‘Malthusian Trap’, that is the reversal of initial gains in living standards. High populations were sustained by agricultural growth initially, and later by more general economic growth, without a large decline in living standards and a reversion to slower population growth.

Not only did agricultural output grow, but so did agricultural productivity based on labour-shedding innovation and investment. In order to feed a higher population and to industrialize, that is to feed those living in towns and engaged in non-agricultural activities, it is necessary to find ways of generating rising output per agricultural worker to allow a ‘release of labour’ to other sectors. Crafts pointed out that this requirement was met by British agriculture in the first half of the eighteenth century. Productivity growth in agriculture was faster than in any other sector of the British economy, and labour productivity in the sector was the highest in Europe. Not only this, but Britain reduced the share of its male labour force in agriculture, releasing this in the main to industry, and it urbanized, doing both at much greater speed than its European neighbours.

There is so far nothing fundamentally new in this presentation of the British pattern of development, apart from the earlier dating of the rise in agricultural productivity. What Crafts did point out, however, was the coincidence of high rates of agricultural growth along with ‘release of labour’, yet comparatively low rates of increase of industrial output. This led him to investigate the distribution of the labour force and productivity growth in the manufacturing and commercial sector.

It was clear from the new social tables devised by Lindert and Williamson that Britain in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries had much higher percentages of its population in commerce and industry than previously thought, but the characteristics of employment of this population were only made clear by data from the 1831 census summarized by Wrigley. This revealed that much higher percentages of this industrial and commercial labour force were to be found in retail trade and handicraft than in manufacturing for distant markets. Crafts’s breakdown of industrial output also showed a large divergence in both the growth of real output across individual industries, and in the percentages of value added contributed by these industries. Industrial output until the nineteenth century was, on Crafts’s estimates, dominated by industries which showed little consistent dynamic performance. In his words,

Table 1.4 Patterns of employment, income, expenditure and residence (%)

much of British ‘industry’ in the first half of the nineteenth century was traditional and small-scale, and catered to local domestic markets. This sector, responsible for perhaps 60 per cent of industrial employment, experienced low levels of labour productivity and slow productivity growth—it is possible that there was virtually no advance during 1780– 1860.8

Some of those industries which initially contributed relatively small proportions of value added were also the glamorous innovative industries which captured contemporary imaginations—cotton and iron. The remarkable growth in real output of the cotton industry, in particular, from 4.59 per cent per year in 1760–70 to 12.76 per cent per year in 1780–90 should be combined with its contribution to industrial output of only 2.6 per cent per annum in 1770, rising to 17 per cent in 1801 and 22.4 per cent in 1831. Cotton’s performance was remarkable, but it was not sufficient to overcome the deadweight of most other British industry, traditionally organized and serving only home markets. It was primarily to this traditional industry that most of the labour ‘released’ by an innovative agricultural sector migrated, and Britain became ‘overcommitted’ to these labour-intensive manufacturing activities.9

Britain’s rapid productivity growth in those manufactures which were traded internationally did give her a large comparative advantage in those activities, and she scooped international markets in cotton. And indeed this was a major achievement, for throughout the nineteenth century cotton textiles constituted the largest part of world trade. This achievement, narrowly based on one industry, accounted for Britain’s international position throughout the nineteenth century. As Crafts has pointed out, by the midnineteenth century Britain was exporting 60 per cent of its cotton output, in comparison with France’s 10 per cent. Cottons accounted for half of British exports during the twentyfive years before then, and Britain controlled 82 per cent of the world-market for cotton cloth even as late as the 1880s. Overall, Britain’s exports were virtually all manufactured commodities (90 per cent), and she exported a comparatively high proportion of her total industrial output (25 per cent compared to France’s 10 per cent).

Figure 1.1 Britain’s development transition in European perspective

Source: Crafts, ‘British Industrialisation’, table 2.

Yet the end result of this spectacular achievement from what was initially such a new and minor industry in Britain was ultimately disappointing. The British story was one of the ‘pain of structural change, but without the reward of rapid income growth’. The success of cotton masked the backwardness of other sectors, and this unique model of success was built on short-term strategies of providing ‘low-wage factory fodder’ rather than high technology industries and a skilled workforce.10

The association of high growth rates in agriculture, urbanization and the deployment of labour to a low productivity industrial sector has provided the basis for a much more far-reaching version of the ‘continuity’ thesis of the Industrial Revolution. This is E.A.Wrigley’s depiction of the period until the mid-nineteenth century as one dominated by ‘organic’ sources of raw materials and ‘natural’ technologies. It was an economy of definitely limited growth prospects, confirming the Malthusian and Ricardian barriers of population growth and resource scarcity. Nature, not technology, dominated the economy of the so-called Industrial Revolution. Williamson had pointed out that Crafts’s estimates confirmed the classical economists’ pessimism that between 1761 and 1831 the difference between the rate of growth of capital and that of output was trivial and failed to offset the impact of increasing land scarcity. Wrigley reinterpreted the analysis of Adam Smith and Thomas Robert Malthus to underwrite the new estimates. He argued that the classical economists were right to argue as they did—‘their reluctance to envisage the possibility of large gains in individual productivity finds support in…Crafts’s estimates’. Their systems were dominated by ‘negative feedback loops’— most of the economic changes taking place until the 1830s and 1840s were thus best understood within the framework they posed of constraints of land or resource scarcity and population growth. The break beyond these barriers only came with the deployment of inanimate sources of energy and inorganic sources of raw materials.

The natural technology of the day, though demonstrably capable of substantial development, especially under the spur of increased specialisation of function, was not compatible with the substantial and progressive increase in real incomes which constitutes and defines an Industrial Revolution…the raw materials which formed the input into the production processes were almost all organic in nature, and thus restricted in quantity by the productivity of the soil.11

Power sources and raw materials, based as they were in natural substances, under this regime, were subject like agriculture to declining marginal returns to land.

Wrigley placed eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century England in an advanced stage of the organic economy. His advanced...