- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The roots of our modern world lie in the civilization of Mesopotamia, which saw the development of the first urban society and the invention of writing. The cuneiform texts reveal the technological and social innovations of Sumer and Babylonia as surprisingly modern, and the influence of this fascinating culture was felt throughout the Near East. Early Mesopotamia gives an entirely new account, integrating the archaeology with historical data which until now have been largely scattered in specialist literature.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

SozialwissenschaftenSubtopic

ArchäologiePart I

Setting the scene

Figure 1:1 The Near East 3200–1600 BC

1

Mesopotamia: the land and the life

The name ‘Mesopotamia’, coined for a Roman province, is now used for the land between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, and in many general books it features as the eastern horn of the ‘fertile crescent’. The Mesopotamian heartland was a strip of land wrested by human vigilance from adverse climatic conditions. Its geography is essential to the understanding of its history: it defines the lifestyle of the agricultural community, and thereby of the city. It preordains the location of settlements and of the routes between them. Extremes of temperature and abrupt changes in landscape divide the area into very distinct environments, which can be blocked out on a map much more clearly than in most temperate parts of the world. The different zones favour or impose different lifestyles, which have often coincided with ethnic and political divisions and so have a direct impact on history. Sometimes it is the physical conformation of the country that has an obvious effect on its human geography: mountain ranges act as barriers to communication, plains enable it and rivers channel it. Major political units grow up in areas of easy communication, whether in the South or North Mesopotamian plain – Sumer, Babylon, Assyria – or on the Iranian or Anatolian plateaux – Elam, the Hittite Empire, Urartu; the intervening mountain ridges and valleys of the Taurus and Zagros, like so many mountainous areas in the world, foster local independence and discourage the rise of larger groupings, political, ethnic and linguistic. Here there were never major centres of cultural diffusion, and it was on the plains of North and South Mesopotamia that social and political developments were forged.

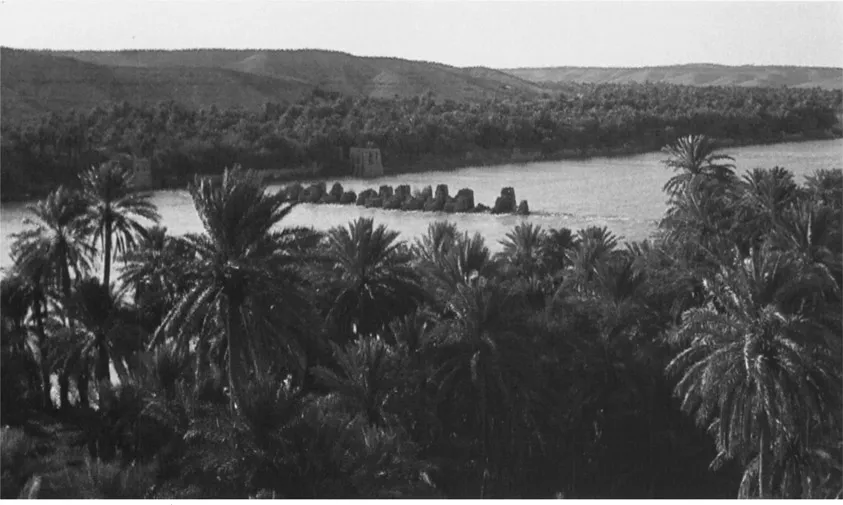

Our approach to Mesopotamia is that of many westerners before us, from Herodotus on, drawn by the reports of ancient cities in a fertile plain. Coming from the Mediterranean past Aleppo, the point of departure is a quay on the right bank of the Euphrates where it flows almost due south after leaving the Turkish mountains. Here at different times Zeugma (Birecik), Carchemish, Emar, and before history Habuba Kabira were the principal ports. As we float downstream, we leave behind us the agricultural lands which stretch almost unbroken from the Euphrates along the foot of the Turkish hills, and the river cuts its way through a dry plain on each side (Figure 1:2). Here and there along its course there is a village, or sometimes a small town, with orchards and crops flourishing on the alluvial soils left by the river and occasional side wadis in the bottom of the valley, but in the entire 700 km stretch the places of historical importance can be counted on the fingers of one hand: just below the junction with the Habur was the city of Terqa, already important in the third millennium BC as recent excavations have shown, and another 80 km downstream, where the valley bottom opens out to a width of 15 km, lies Mari. Below this, the ancient island of Ana, now sadly under the waters of another dam, and Hit, where the bitumen bubbling up from underground was exploited long before Herodotus tells us that Nebuchadnezzar used it for the walls of Babylon.

Figure 1:2 The Euphrates at Ana looking east. In the river, piers of a medieval bridge link the right bank to the island; on each side brown cliffs rise above the date palms, flanking the valley.

The desert

Most of the landscape, if we disembark and scale the dusty cliffs each side, is empty, and, except in spring, brown. On the left is the Jazirah, which stretches to the Tigris and the fringes of cultivation south of Mosul, on the right the Syrian desert. Both are the ancestral home of the nomad. The desert, never uniform in character, encloses Mesopotamia on the west from the Euphrates bend down to the head of the Gulf, and is penetrated by only a few routes open to the traveller from outside, notably that taking off from Mari and making west to the oasis of Tadmor (classical Palmyra) on the road to Damascus. Until very recently it retained a fauna of its own with clear links to Africa: ostriches were hunted by the Assyrians, cheetahs were reported this century, and far down in the Arabian peninsula the hartebeest. The wild ass, or onager, is another casualty of modern times, but their herds were vividly described by travellers such as Xenophon and Layard.

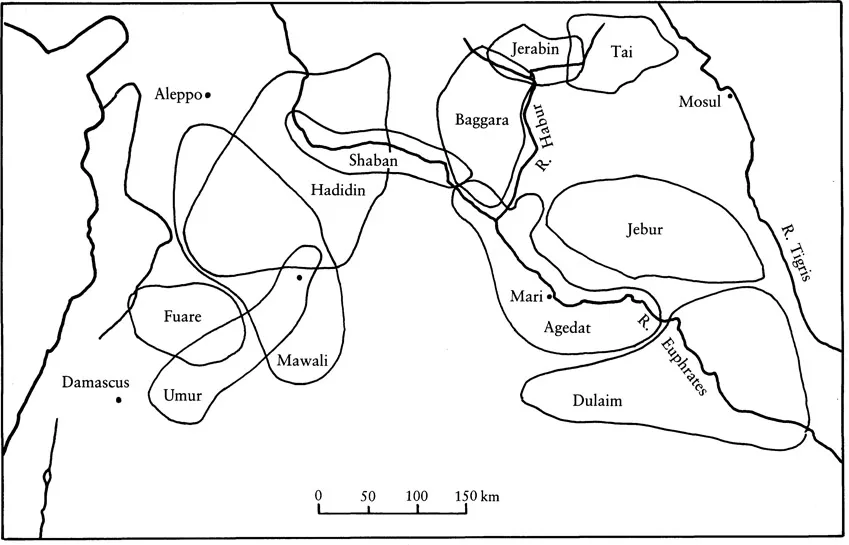

Today’s desert nomads are almost exclusively of Arab stock. Similar well-defined tribal groups were present round the fringes of settled lands as early as our records go, but one cannot assume that the modern lifestyle is of ancient origin. The bedu of the western romantic consciousness and Arab heroic tradition is a relative newcomer: as one penetrates deeper into the desert, pasturage becomes scanter and distances from well to well increase, making long-distance travel impossible without the camel, with its greater speed and endurance in desert conditions. As far as we know, before about 1000 BC the camel was not domesticated, and hence the ‘archetypal’ pure beduin lifestyle impossible.1

Figure 1:3 Traditional grounds of sheep-rearing tribes in Syria and North Mesopotamia. (After Wirth 1971, Karte 11)

A great deal has been written in recent decades about nomadism in the ancient Near East, stimulated largely by the fascinating light cast by the documents from the palace at Mari, seat of a recently settled nomadic dynasty. As more detail is recovered it becomes increasingly clear that, although the contrast between ‘the desert and the sown’ was always vividly felt, they were never entirely independent of one another. Beduin often camp well within the limits of agricultural settlement today, finding grazing for their sheep. They act as shepherds for the urban landlord, or villagers who have larger flocks than they can graze in their own fields. The Arab tribes of the Jazirah do not roam aimlessly across the land, seeking grazing wherever they can find it, but have well-established summer and winter pastures, to which they move at the change of season every year along known routes, and there are often small settlements in the winter grounds where part of the tribe may stay and engage in agriculture (Figure 1:3). Grazing rights to different areas are agreed both within the tribe and with other tribes and any settled inhabitants of the areas in question.2 All the same, this is a fruitful ground for dissent, and the location of the summer grounds must have varied throughout history as climate or politics moved the southern fringes of settled agriculture closer to or further from the hills. Much of the political history of both South and North Mesopotamia revolves round the tensions between these different lifestyles, and we shall return to the role of the nomad below (chapter 4).

The southern plain and marshes

Eventually, after much meandering, the Euphrates enters the southern alluvial plain. The contrast with the lands to the north is intense, and is the direct consequence of the climate and the physical geography. Geologically, South Mesopotamia is of very recent origin – an alluvial deposit laid down by the two rivers (and their predecessors) in the deep trench formed between the Arabian shield to the west and the sharp folds of the Zagros mountains. The most obvious characteristic of this plain is its flatness. As much as 500 km north of the Gulf coastline, the general landscape is still less than 20 m above sea level, giving a gradient of 1:25000. This has various consequences. There is little to restrain a river which chooses to change its course, and in the space of a few years the natural landscape can change from barren sandy desert to marsh. It is very easy to direct water from the rivers on to the land, but much less easy to divert it and drain the land. The most conspicuous features of the landscape are the ancient sites, and the solid green blocks of palm-groves. Only the lowest of these are concealed by the long banks each side of ancient or modern canals. Although there can be much local variation, as we shall see later, the patterns repeat themselves time and again, and the landscape changes little overall.

Figure 1:4 The marshes of the Tigris–Euphrates delta.

Southwards the plain gives out where the rivers, united today at Qurnah into the Shatt al-Arab, lose much of their water into wide marshlands before reaching the open waters at the head of the Gulf. Here villages of reed houses perch on islands of vegetation (Figure 1:4). For mile upon mile one can slide through avenues of reeds which far overtop a man’s height, in a silence broken only by the calls of birds and the crashing of water buffalo in the thickets. Much romanticism has been lavished on the marsh dwellers of the south by European writers, attracted by their reed architecture and primeval lifestyle, as well as their extreme habitat with hidden ways through the reeds and the sense of penetrating a world apart. We have detailed accounts of their boats and houses, of their fishing and herding activities, and of their social customs. Life in the marshes is built round reeds and fish, with few concessions to the technical advances of civilization, so that it need have changed very little since neolithic times; but whether it is in fact an archaic survival or a much more recent adaptation to a marginal environment is another question. According to Salim, the usage of the marsh dwellers themselves confines the term Ma’dan to the buffalo breeders, and a good proportion of them are, or claim to be, descendants of beduin tribes.3 Tradition also relates that many of the marsh dwellers are descended from escaped slaves from the time of the Zanj rebellion in the ninth century AD. In any case, since water buffalo were introduced to Iraq during the early Islamic period, it is deceptive to treat the ‘marsh Arabs’’ way of life as inherited unbroken from prehistoric times. As Salim’s study makes clear, the establishment of stable political conditions tends to break down the isolation of the marsh dwellers, and in early Mesopotamia several of the principal cities were on the fringes of marsh or sea. True, we hear from Sennacherib about campaigns against Chaldaeans living ‘in the middle of the marshes’, but they must have taken up this life precisely during an absence of strong central authority. It would be wise, therefore, while accepting that the marsh dwellers of today may be living a life not unlike that of the earliest inhabitants of Ur or Eridu, not to assume that they represent an archaic survival.

The eastern flank

The marshes also stretch north for some 200 km along the east side of the Tigris as far as Amara, cutting Mesopotamia off from direct access to the neighbouring plain of Susiana, which was always an important centre of its own. To reach Susiana from Mesopotamia two routes were possible: a narrow and uncertain passage between the marshes and the Gulf to the south-east,4 or the more normal route pushing north-east until the marshes give way to dry land and then turning to the south-east, skirting the flank of the Zagros, and during all our time span passing the city of Der. Precisely how far north this point was must have varied, and the nature of this route depended on the level of exploitation of the waters of the river Diyala: when this was actively pursued, irrigation from the left bank fingered out into the lands to the south-east, and enabled the growth of major cities such as Esnunna (Tell Asmar) or Tell Agrab – sites which are now once again within the limits of cultivation but lay in high desert in the 1930s when the Oriental Insitute of Chicago began excavations there.

While the Diyala waters created a corridor between the north-eastern corner of the Mesopotamian plain and Susa and beyond, the river also served as a principal route for those travelling due east and even north as well. The eastern route is variously called the Silk Road or the Great Khorasan Road. After crossing the Iranian frontier it soon has to climb nearly 1,000 m in a spectacular pass called Tak-i Girreh to the plateau, leading through Kermanshah to northern Iran and on eastwards to the cities of Central Asia and finally China. The northern route unites travellers from Susiana with the even busier route from the Mesopotamian plain. From Baghdad, and before that from any of the great cities at the northern end of the plain, the road to Assyria did not head due north along the banks of the Tigris like the modern asphalt, but sought more hospitable terrain where villages were more frequent, supplies of food and water easier to come by, and there was less risk of marauders. This route, formalized by the Achaemenid kings as the Royal R...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of texts

- List of figures

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Note

- Prologue

- Part I Setting the scene

- Part II The institutions

- Part III The economic order

- Part IV The social order

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Early Mesopotamia by Nicholas Postgate in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Archäologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.