![]()

1

INTRODUCTION TO THE NEOLITHIC

If you ask a group of people when the modern period began, some will point to the invention of digital communications. Others, with a slightly longer view of things, may mention the end of the Second World War or the beginning of the first one. Those who’ve studied western history usually answer that the Industrial Revolution, or the Enlightenment, or maybe the Italian Renaissance marks the beginning of modernity. But the truth is, the basic patterns of modern life developed more than 10,000 years ago, in a period called the Neolithic, when people’s lives were irrevocably altered by the single most profound change in human cultural history – the invention of agriculture.

This book describes what happened to our ancestors as they changed from hunting and gathering to farming. I begin by defining some basic terms and concepts, including a brief description of archaeology, the main source of information about Neolithic culture. After a summary of the natural mechanisms that underlie domestication, I address the following questions: When and where did the shift from hunting and gathering to farming first take place? What plants and animals were the first ones to be domesticated? Why did early agriculturalists concentrate on those particular species? How did life change when people began farming? What did the first villages look like and why was their development significant? Who were the first craft specialists and what did they do? What happened to human health as a result of the Neolithic Revolution? What do archaeologists know about the social, political and religious life of Neolithic people? And finally, why did the transition to farming occur?

Prehistory

As you will see, in a surprising number of ways the lives of the first Neolithic people were not much different from yours. They lived in houses; ate bread, vegetables, fruit, meat, and cheese; used fired clay dishes; wove cloth for clothes; liked luxury goods; and buried their dead in special places. But in one way, Neolithic life wasn’t at all like the twenty-first century: Neolithic people didn’t write. Cultures that haven’t invented writing are referred to as prehistoric, and for more than two million years (until about 5,000 years ago when writing was invented in Mesopotamia and Egypt) everyone on earth was prehistoric. Once writing appeared most people moved into history, but in some parts of the world prehistoric cultures survived well into the twentieth century.

Scholarly interest in prehistory in general, and the Neolithic in particular, is a fairly recent phenomenon. It arose in the mid-nineteenth century, when Europeans studying pre-Roman cultures divided them into three stages based on the materials used for their tools: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. John Lubbock, an English nobleman who wrote popular science books, noticed that some Stone Age tools had been shaped by grinding or polishing instead of by the more common chipping techniques, so he subdivided the Stone Age into two phases: an earlier Paleolithic (or Old Stone Age) phase, when only chipped stone tools were made; and a later, Neolithic (or New Stone Age) phase during which ground stone tools were invented. Although methods of tool manufacture aren’t the only distinctions between Paleolithic and Neolithic cultures, Lubbock’s division, which he published in a 1865 book on archaeology called Prehistoric Times, is still used today. During the twentieth century, particularly since the 1950s, new excavations and new scientific ways of processing data have produced a flood of information about everything from Neolithic marriage customs to prehistoric tooth decay. Today, we can no longer think of Neolithic people as Stone Age savages. Instead, we must view them as the founders of modern life, and among the most creative problem-solvers the world has ever known.

Archaeological assumptions

Because it lies in prehistory, almost everything that we know about the Neolithic was discovered archaeologically. Archaeologists study the physical – or material – remains produced by human activity. Any place with material remains is by definition an archaeological site: a meadow is simply a meadow, but a meadow with a broken bottle on it is a site because the bottle is a physical record, maybe the only record, that in the past someone was in the meadow and did something while there. (As you’ve probably noticed, according to this definition, almost every place on earth is a site.) The ultimate goal of an archaeological excavation is to collect as much information about the past as possible, so it’s lucky that ancient people weren’t any tidier than we are. The debris they left behind is just what you’d find in an abandoned village today, and in order to study it, archaeological teams include all sorts of experts: architects, art conservationists, art historians, biologists, botanists, chemists, economic theorists, ethnographers, geneticists, geographers, geologists, graphic artists, historians, linguists, materials scientists, osteologists, pathologists, photographers, physical anthropologists, physicists, sociologists, surveyors, and zoologists all study archaeological data. And all of them, regardless of their backgrounds, share a set of assumptions about the archaeological process, and about what excavations can reveal about the past.

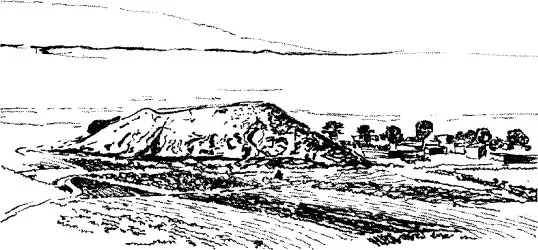

Figure 1.1 Centuries of rebuilding on the same site can create mounds like this one in Turkey with its attached modern village.

The most basic archaeological assumption is that sites are created over time – even that broken bottle in the meadow is the result of several sequential actions. Material remains accumulate in layers, or strata (usually identified by significant changes in the finds or by visible differences in the soil). On some sites the strata are so thin they’re hardly visible above the ground, but Neolithic villagers from Iran to Greece built their houses using mudbrick, and on these sites the living debris built up in thick layers that eventually created large mounds that can be seen for miles: they’re referred to variously as magoulas, tepes, tels or tells, and höyüks, all of which simply mean hill. But whether the layers are thick or thin, archaeologists assume that they contain a chronological record of what happened on a site, with the earliest evidence at the bottom and the most recent evidence at the top. This concept of chronological deposition is so important that it’s reflected in two of the four Laws of Archaeology: the Law of Stratigraphy – archaeological layers are deposited one at a time – and the Law of Superposition – the lowest layers were deposited first.

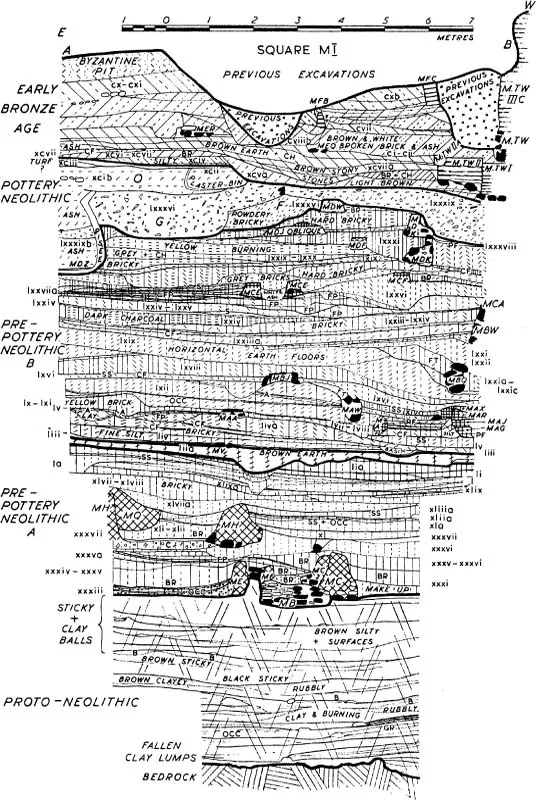

Understanding that archaeological strata are deposited over time, and that layers near the bottom are older than those near the top, allows archaeologists to trace cultural changes on a site. For example, when archaeologists write that the process of animal domestication took place in a particular place, what they mean is that they’ve compared the animal remains in the strata, and seen a change from wild forms in the lower (earlier) levels to domestic forms in the upper (later) levels. A report that ceramic technology was introduced from the outside means that pottery suddenly appeared in one layer and was found in all subsequent layers. And when excavators report that social elites developed on a site, they base that conclusion on a sequence of changes in the material remains from level to level that suggest the evolution of a class system.

Figure 1.2 This vertical section from Jericho illustrates the way archaeologists record complex stratigraphy on a multi-period site.

The second assumption made by all archaeologists is that everything found on a site can be assigned to one of four broad categories of remains. The first category is artifacts, which are defined as portable objects made or modified by people. Pottery jars, stone tools and beads are examples of typical Neolithic artifacts. The second category, features, is used for nonportable artifacts like ovens and hearths. The third category is structures, and it includes everything from houses and sheds to roads and bridges. And finally, there are ecofacts – animal and plant remains that haven’t been made into artifacts or used in structures. If a length of wood found on a site functioned as a digging stick it’s an artifact, but if it was used as kindling it’s an ecofact. Kitchen scraps and pollen grains are ecofacts; and so are human bones and teeth, although they’re usually referred to as human remains.

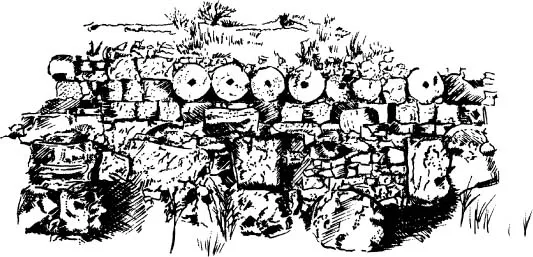

The third assumption archaeologists make is that almost all of the artifacts, features, structures and ecofacts that ancient people left behind have disappeared. In the last hundred thousand years, most people have chosen to live in temperate climates, where the weather alternates between hot and cold, and wet and dry: the worst possible conditions for the preservation of organic material.1 Inorganic remains have a better chance of surviving the weather, but they’re often destroyed by later people on the site. New inhabitants knock down old buildings to make space for newer, and larger, ones (a process that’s all too familiar in modern communities). Sometimes the old building materials are reused, but usually they’re thrown away. Even if archaeological remains survive urban renewal, armies (and mobs) pull down walls, tear up roads, burn houses, loot graves, deface art and melt down metal artifacts. When you consider the amount of natural decay, plus this purposeful destruction, it seems miraculous that anything at all survives after a few hundred years, much less the 10,000 years since agriculture was first invented.

Figure 1.3 Villagers built this wall using column drums from a nearby Roman city.

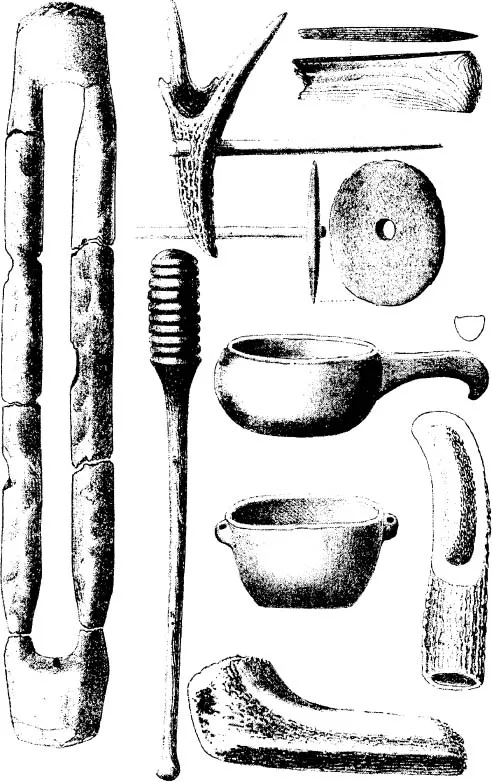

On the other hand, some natural environments encourage preservation. Organic remains survive surprisingly well when the environment is constant: consistently dry deserts, constantly wet lake bottoms and bogs, and constantly cold glaciers have all produced well-preserved Neolithic remains. The body of the famous European Iceman, Ötzi, survived for over 5,000 years because for most of that time it was frozen.2 Examples of Neolithic sites with consistently wet environments include 7,000-year old Hemudu in China, where archaeologists found wooden architecture, red lacquerware bowls, rice grains and thousands of bones and bone artifacts; the Swiss lake villages described at the end of the chapter; and the Ozette site on the Northwest American coast (destroyed by a mudslide) where the entire contents of the houses were preserved.

Ethnographic analogy

A different type of archaeological assumption is based on analogy – the concept that like objects can be compared. Archaeologists study material remains, and since they know that people today surround themselves with things that reflect what’s important to them, they assume that ancient artifacts reflect what was important to ancient people. This theory is supported by ethnographic reports. Ethnographers are cultural anthropologists who study individual cultures by living in them and observing the way people behave. All archaeologists rely on ethnography to some extent, but prehistorians don’t have any other sources of information about the people they study, so they find ethnographic reports particularly useful. And since for much of the twentieth century ethnographic studies concentrated on traditional societies (many of which were pre-literate) there are plenty of sources with insights into why prehistoric people make and use various artifacts. For example, in almost every known culture – both historic and prehistoric – hemispherical bowls are used to hold liquids and soft foods like porridge. Archaeologists apply ethnographic analogy and assume that ancient hemispherical bowls were made for similar foods.

Archaeologists also apply the concept of analogy to broader issues than the probable function of an artifact or feature. Ethnographic reports reveal that there are universals of human behavior. In all known societies people work hard to make a living, love their families, worry about their health, and mourn their dead. There are also universals of social organization: all societies have a political structure, a system of social organization, and a form of religion. Based on ethnographic analogy, archaeologists assume that prehistoric people were a lot like us, and that their shared values guided them as they interacted with their families and other group members. In other words, like us, prehistoric people lived in cultures. When anthropologists and archaeologists talk about a culture, they mean a group of people with a set of common attitudes and customs that they transmit from generation to generation. This definition is implicit in names like the Linearbandkeramik Culture – the Neolithic people in Europe who made and used Linear Band decorated pottery – and the Mississippian culture – Neolithic people who farmed along the lower Mississippi River. The last use of analogy has to do with specific attitudes and beliefs. Archaeologists know the explanations living cultures give for why they bury their dead, so through analogy archaeologists might propose that prehistoric people who buried their dead had similar reasons.

Figure 1.4 Wood, bone, and antler artifacts were preserved for over seven thousand years in the muddy bottoms of Swiss lakes.

Dating

Now we turn to archaeological dating. How do archaeologists know that a site is Neolithic? The most basic answer is that they recognize the features, structures, and particularly, the artifacts typically made by Neolithic-stage people. Another common strategy is to examine the stratigraphic sequence on a site, and if there are the remains of pre-Neolithic cultures below a given layer, and the remains of post-Neolithic cultures above, it’s likely that the layer in the middle is Neolithic. But unlike the cultural term “Roman,” for example, “Neolithic” doesn’t refer to a specific time in the past. Instead, it refers to a general stage in cultural development, and people around the world moved into this stage, and then beyond it, at different times. So while archaeologists have always been able to date a Neolithic site relatively (as earlier than or later than other sites in the region), until about fifty years ago they had no way to date prehistoric sites absolutely – in terms of years ago. Then a series of scientific breakthroughs radi...