![]()

1

INTRODUCTION. A FOLK WHO WILL NEVER SPEAK: BELL BEAKERS AND LINGUISTICS

Alexander Falileyev

This will be a mostly unexpected contribution to this splendid volume. First of all, it is intended to discuss some aspects of the Bell Beaker problem from a completely different angle: from the point of view of comparative and indeed Indo-European linguistics. It is widely known, of course, that some archaeologists do pay attention to the problems of identifications of the Beaker Folk with the speakers of this or that language or proto-language in European prehistory, and various suggestions are available. They are, however, normally criticised, sometimes heavily, by linguists and even by some archaeologists. In this respect my approach to this set of questions seems to be again unexpected, as I am of the opinion that nearly all of these suggestions are allowable, or at least, tolerable. The real problem here lies rather in the field of comparative linguistics, not archaeology. It should be reminded that we, linguists, do not normally do dates, to use the title of the article by A. and R. McMahon which is surely known to prehistorians, as it was published in one of the McDonald Institute monographs (McMahon and McMahon 2006). This makes any chronological association of the speakers of a language with a set of archaeological facts in prehistory effectively impossible. There are some other drawbacks in the study of languages and their relationships in early Europe, which affect these identifications, and I will address some of these issues below. At the moment two linguistic associations of the Beaker Folk are popular at least among some archaeologists and linguists. First I will offer some brief comments on the subject “Old Europeans” (in terms of the theory of H. Krahe, not of M. Gimbutas) and the Phenomenon, and then I will turn to the notoriously ever-lasting identification of the Bell Beakers and the Celts.

Old European (Alteuropäisch) is the term introduced by Hans Krahe for the language of the oldest reconstructed stratum of European river names in Central and Western Europe. According to Krahe and his follower, these hydronyms show pre-Germanic, pre-Italic, pre-Baltic and pre-Celtic features. The geographical distribution of these names to a great extent coincides with that of Bell Beaker finds, and it is not surprising, therefore, that these two notions have been associated. We find this association in the works of archaeologists and linguists alike. Thus, to quote from G. Clark and S. Piggott (1970, 289):

“the distribution of river-names belonging to the non-Celtic but Indo-European substrate language (…), present not only in continental Europe but also in Britain and Ireland, would be best explained by referring them to the folk movements involved in the Bell Beaker reflux”.

Similar ideas are expressed by linguists. As P. Kitson (1996, 103–4) maintains,

“Bell-beakers are in fact the only archaeological phenomenon of any period of prehistory with a comparably wide spread to that of river-names in the western half of Europe. The presumption must I think be that Beaker Folk were the vector of alteuropäisch river-names to most of Western Europe”

Taking into account the place this conference was held, it will not be inappropriate to note that Professor Javier De Hoz, in an article considering the processes of Indo-Europeanization of Spain and published by the University of Santiago de Compostela, admits that such an assumption is not impossible (De Hoz 2009, 15).

Indeed, in theory, a correlation between the Bell Beaker phenomenon and the speakers of Old European is not unfeasible. However, the linguistic side of this comparison is really problematic. To start with, the date which has been posited for “Old European” varies. Thus, according to the classical approach of H. Krahe, it should be dated back to ca. 1500; but if we are to follow W. P. Schmid, “Old European” river-names belong to a much earlier date, prior to the differentiation of the IE languages; and an even more complicated scheme is offered by Vyach Ivanov and T. Gamkrelidze. On top of that, these scholars (and some others, see for instance Zvelebil 1995, 191–192 for an “Old European” continuum in the Danube basin in 4500–3500 BC) may have different views on the geographical distribution of the data. These rather contradictive approaches to the problem of Alteuropäisch have usefully been surveyed by N. Sukhachev (2007, 101–117), where further references are provided. Therefore, there is no evident consensus among linguists regarding the time of “Old European” (cf. also Häusler 1995, 225), which already makes an association of it with the Bell Beaker phenomenon problematic. Yet another problem here is the matter of space: even in the classical presentations of the Old European theory the border of the area seems to be stretching eastwards far beyond that of Bell Beakers. Of course, this archaeological area is constantly being widened, and the papers by T. Demcenco, V. Heyd and C. Prescott presented at the conference are very illustrative in this respect. However, the area where Alteuropäisch hydronymy is found, say, in Eastern Europe, will be hardly associated with the phenomenon even in the distant future. Thus, Old European river-names, according to some scholars, are attested in Finland (see Nuutinen 1992, 135–137 with further references). It is worth noting that these are associated with the Battle-Axe culture (Nuutinen 1992, 135).

Apart from that, the very concept of Alteuropäisch is a problem in its own right: text-books on Indo-European linguistics do not normally consider this postulated stage in the history of the Indo-European languages, and many scholars working with the river-names prefer to analyse them as coined in the locally used language(s) (or extinct idioms) rather than to refer to the putative notion of “Old European”. See, in this respect, G. R. Isaac’s work on the ancient hydronymy of modern Scotland (Isaac 2005) or, to take another edge of the continent, the research by S. Yanakijeva who argues that there is no need to use the label Alteuropäisch in a discussion of the river-names in ancient Thrace (Yanakijeva 2009, 183). On a methodological level it may be considered that, according to N. Sukhachev (2007, 117):

interpretations, offered for “Old European” by H. Krahe, W. P. Schmid, T. V. Gamkrelidze and Vyach. Vs. Ivanov are based on different concepts of “pre-history” and reflect on incompatible cultural and historical reconstructions; the linguistic argument is secondary,

and according to G. R. Isaac (2005, 190):

“Old European” was invoked as a deus ex machina theory in the past to solve problems which, I believe, have been shown by later research not to be the problems at all.

Needless to say, the concept, notwithstanding the efforts of its critics, still has its adherents. It seems that the problem of Alteuropäisch should be freshly addressed in a systematic and comprehensive manner to revisit the essence of this model and the relevance of its manifestations. Therefore, for the time being, a reference to “Old European” in a discussion of Bell Beaker linguistic attribution by default raises more questions than it intends to answer.

As known, the very existence of the Celts in prehistory is the focus of a debate lasting for the past two decades. A “Celtosceptic” approach, also known as “New Celtic” (e.g. Collis 2010) denies it, while for linguists the reality is that a form of Celtic was spoken in prehistory, whatever the pots these people were using. This range of question has been comprehensively surveyed by S. Rodway (2010) and I will just remark that the word “Celt” below denotes a speaker of a Celtic language.

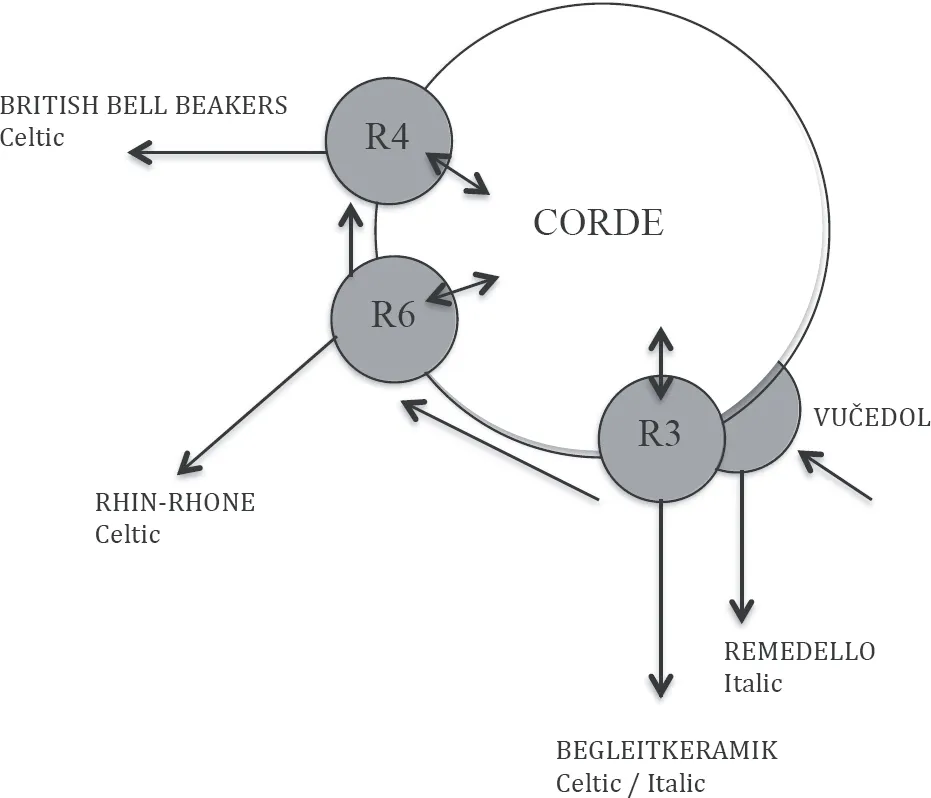

The association of the Bell Beaker Folk with the ancient speakers of Celtic is already traditional. We find it in the works of Celtic linguists and historians and Bell Beaker archaeologists. This approach has triggered consequences. Thus, the identification was adopted, although somewhat reluctantly, in very influential The Celtic Realms by Nora Chadwick and Myles Dillon (1967, 18–19), and is still alive and well in a number of recent publications on various Celtic linguistic matters. A more elaborate association of the Folk or, rather, Phenomenon, with the Celts comes from the camp of archaeologists. Thus, at the 1998 Beaker Congress Professor A. Gallay (2001) sought to show that the Pre-Celts and Pre-Italics emerged from the complex of Bell-Beaker setting (Fig. 1.1).

Nearly a decade later Professor Patrice Brun (2006, 30) addressed this subject, but from a different standpoint:

Since there is no evidence that the regions of Western Europe where Celtic languages are still spoken today became Celtic after 1600 BC, they must have become so at an earlier date. Before 1600 BC, the only time when the zones which gave rise to the north-Alpine and Atlantic complexes shared similar material and structural characteristics was the second half of the 3rd millennium BC. This was the well-known Bell Beaker “package”. Linking all the regions where a Celtic language was later to be spoken, this community represents a unique situation.

Fig. 1.1. Pre-Celts and Pre-Italics in Bell-Beaker setting according to A. Gallay (2001).

Fig. 1.2. Indo-European languages: glottochronological scheme of S. Starostin (Blažek 2007).

Similar views, varying in sometimes valuable detail, have been expressed by archaeologists dealing with the Celtic problem (see for instance Lorrio 2006, 50, with further references). These associations of the Bell Beaker Folk with the speakers of an early form of Celtic (or proto-Celtic) may be of course possible, and again it is comparative linguistics that hinders this equation. There are a lot of problems here, and these could be summarised as follows.

First, there is – once again – the matter of chronology: there is a continuous dispute on the dating of the Common Celtic, ancestor of the modern and ancient Celtic languages, and there is no tool which can provide a universally accepted dating. As linguists know, the only branch of the discipline which operates with absolute chronology is the so-called glottochronology, a part of lexicostatistics which deals with chronological relationship between languages. A look at the results of the most recent research indicates that glottochronology, in its latest model, labelled “calibrated” (linguists are learning from archaeologists!), dates the split of Common Celtic, that is the time when it started diverging into its branches, to 1100 BC. According to the same methodology, created by M. Swadesh and creatively elaborated by S. Starostin, the emergence of Common Celtic out of the continuity of other IE dialects (after pre-Hittite and pre-Tocharian were materialised) should be dated to the period 3350–3020 BC (Blažek 2007, see Figs 1.2 and 1.3). This gives us a span of at least two millennia, 3350–1100 BC, and chronologically the Beaker Folk fit here perfectly.

The problem is that many historical linguists tend to consider this method with extreme caution. There is an ongoing argument on the validity of glottochronology, an issue I will not discuss here. Instead it will be suffice to mention a following paradox. Some linguists argue that a Celtic language was introduced to Ireland in the Late Bronze Age. An alternative view is that it appeared on the Emerald Island only in the earliest centuries of the new era (see further references in Sims-Williams 2012). There are also other datings in between, of course. These views, based on purely linguistic observations in conjunction with some historical (sometimes archaeological) facts, are accepted by some linguists and rejected by others. However, the very fact of such a chronological divergence seems to speak for itself. It should be stressed that these observations could not, in fact, compromise a possible chronological comparability of the Common Celtic linguistic period and the Bell Beaker age. Yet this possible chronological contemporaneity does not by default equate the speakers of the language with the people or peoples responsible for the Beaker Package.

Fig. 1.3. Celtic languages: glottochronological scheme of S. Starostin (Blažek 2007).

The second point to be raised here is purely linguistic again, and concerns the relationship of Common Celtic with other early Indo-European dialects. In the scheme of S. Starostin we can see that Celtic was the third branch after Hittite and Tocharian to separate from the Indo-European continuity. In this Starostin agrees with the model presented by D. Ringe et al. (2002), but there are also other schemes available, e.g., by E. Hamp, T. Gamkrelidze and Vjach. Ivanov (see references in Blažek 2007), and these place Celtic in a different position of this hypothetical tree. Needless to note that the validity of the schemes has been questioned for a long time, and other approaches to the formation of the proto-groups of IE languages are available. Moreover, in recent years, and this is not reflected in any of the existing diagrams, a new theory has been offered. Professor K. H. Schmidt (1996) claims that Proto-Celtic, traditionally taken as a Western IE language, has an important set of traditionally Eastern IE linguistic features. Schmidt (1996, 22–26) lists several joint innovations which connect Celtic with the Eastern IE idioms, namely the inflected relative pronoun *ios (Indo-Iranian, Greek, Slavic, Phrygian, and Celtic), desiderative formations with reduplication and a thematically inflected s-stem (Celtic and Indo-Iranian), and future in *-sje-/-sjo- (Celtic, Indo-Iranian, Baltic, Slavic, and possibly Greek). The expansion of productivity of the sigmatic aorist (Slavic, Indo-Iranian, Greek, and Celtic) has also been added to this list (Isaac 2010, references). This theory is of importance as it, in fact, reconsiders the areal configuration of early IE dialects. Following this theory, the Italo-Celtic linguistic, and hence historical unity, advocated by the majority of Indo-European...