![]()

Four

A Drop of Water,

World Trade Center Dust

56 I propose to pay attention to some things that photography shows us. We show photography what to show us, we feel we see what photography shows us in the faces and things that it shows us. But photography also always shows us things we would have preferred not to see, or don’t want to see, don’t know how to see, or don’t know how to acknowledge seeing.

In this book the quality of my attention and the languages in which I can articulate my responses vary, but they will not cross into regions ruled by the sublime, affect, “the pangs of love” or pity, “madness,” or—this was Barthes’s final thought in Camera Lucida, faintly echoing Bataille—“photographic ecstasy.” (pp. 116, 119) Photographs that concern me do not usually harbor any particular punctum: no local, “intense mutation of my interest”; no “fulguration”; no “tiny shock”; no “satori”; no “explosion” that “makes a little star” on the image. (p. 49) That is all just so romantic, or more accurately late romantic, leftover romantic. It’s stale stuff. Romanticism was once an ocean of metaphors of excess; in Camera Lucida the ocean has dwindled to rivulets. Barthes’s little ecstasy, the punctum, is like the last remaining pinhole of access to the light within photography. He knows it is small: it is a tiny satori, sparkling like a “little star.” Yet nothing matters except that pinprick, that last little death.

The images I want to look at are not as absorptive, dramatic, or theatrical. Mainly, they are just hard to see. Some are violent or unpleasant, and they repel my attempts to look at them. Others are hard in the sense of obdurate: they resist my intention to look, and even my interest in trying. They are “merely” informational, “simply” not beautiful, “wholly” uninteresting. With such images it can be hard just to pay attention, to keep my eyes on the photograph, to focus my faltering interest on the unpromising image.

These hardnesses I am after are neither precious nor rare. Most any photograph has some hardness, something that turns the eye away, and if we choose not to notice, it is because we are looking so intently for the last plangent signs of “love” or “madness.” (“Plangent”: a word Nabokov knew was both rare and excessive; it is the name of a “fundamentally hysterical” chord played on a piano at the end of Lolita, to point up the player’s exquisitely desperate, pitiful and kitschy dying speech.) Little punctures and shocks of all sorts help distract us from photography’s routine hardnesses. If you take the punctum away, or if you take away the desire for it, you can see most photographs for what they also are: things that are flat and hard, and don’t promise much pleasure at all.

57 So here I am, at the boundary of what photographs are too often taken to be, looking outward, in the direction away from all these things—ecstasy, the sublime, the punctum, memory, history, race, gender, identity, death, nostalgia. This is a good time to say goodbye to photographs of people.

What would it be like, I wonder, to go through the photographs I own—the ones I have framed, the ones in my photo books and cabinets and the ones on my computer, the ones in the books and magazines in my home and my office—discarding all the images that have people in them? Which would be easiest to relinquish? Which ones would be so close to me that I couldn’t bear to give them up? I imagine this as a series of farewells, and I am curious to see what will be left of photography when all the people are finally gone.

58 First farewell: unlabeled family photographs. Maybe it is prudent to start with images of unidentified people, the kind that are so easy to find in any antique store or box of old photographs. They can be quite striking and poignant. (“Poignant”: meaning something that prickles, from poindre, “to prick or sting,” from pungere, “to prick.” So like the punctum.)

It’s strange that so many photographs of people I have never known can be poignant. In an antique store I come across an old photograph of a man wearing a box-back shirt and a stetson hat. He looks at the camera (at me) with a smirk, overconfident and standoffish. Did he suspect that generations later his unlabeled photograph would become the object of a sudden and intense but transient fascination? That his real life, which he owned, would become poignant when all its details were long forgotten? He is already dead, she is already dead, he is going to die, we say over and over to ourselves as we shuffle through old photographs in the back of an antique store, vaguely searching for one that has more than the usual background radiation of poignance. Yet the curious man was not unknown to himself, any more or less than any of us are unknown to ourselves, and his image was presumably not much of a mystery to his relatives, so the affecting he-is-going-to-die reaction is not only indulgent solipsism but adventitious voyeurism. That did not bother Barthes, but as I join him in peering at little Ernest I feel a little pang of guilt: I am peeping through a keyhole little Ernest could never have seen.

It is not a hardship to say goodbye to unlabeled family photographs, with their low-level pathos. When I encounter them in antique stores or flea markets, I find them only marginally more interesting than the endless tightly packed cardboard boxes of old postcards, or the glass-top table displays of heirloom watches, war medals, election campaign pins, lost buttons, and multipurpose folding knives. When I catch myself shuffling through a tray of tintypes, it is usually because I am in the mood for a very weak, homeopathic dose of poignant nostalgia, or because I have nothing better to do than look around for some hidden gem that I never quite seem to find.

59 Second farewell: “found photography.”

(There are so many kinds of photographs of people. “Found photography” is subtly different from “vernacular photography,” or “everyday photography,” meaning the whole worldwide practice of family picture-taking, mainly of people, but also of the places they have been. “Travel and vacation photos, family snapshots, photos of friends, class portraits, identification photographs, and photo-booth images,” is how Wikipedia succinctly defines vernacular photography. [At least as of August, 2010.] By that definition, the man in the stetson would be a vernacular photograph, although it could also be counted as an example of professional portrait photography. “Found photography” usually means vernacular photos that have been discovered and reconsidered as art. Vernacular photography practiced in the past hundred years or so, mainly in cities, is also called “street photography.” All of these overlapping categories are distinct from the monumentally scaled “fine art photography” that stormed the art market in the 1990s, although the artists themselves refer to vernacular, street, everyday, family, portrait, and found photography. I am only listing things this way to help me with my farewells.)

To help me give up found photography, I bought a packet of unidentified snapshots from eBay. Because I selected them, and brought them into this book, they are “found photography”: they aren’t quite art, but they are also no longer what they once were. They chronicle a family, whose name has been lost, through two or three generations of lower-middle-class life in what appears to be a cold part of North America. Before I bought them, when they were languishing alongside the 60,000 other photographs then on eBay, they were the very stuff of vernacular photography. They draw me, with an infirm but nearly irresistible force, into a imagined world.

Here is a diffident-looking woman, standing in a small patch of sunlight at the back of her bungalow.

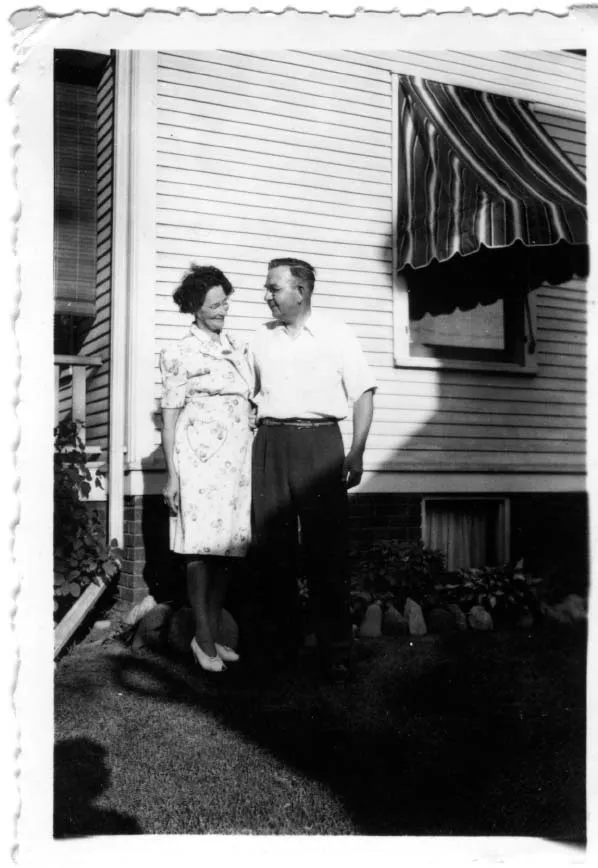

Here is a middle-aged couple, photographed June 4, 1944, at the side of their house. (The date is written rather carelessly on the back.) He has told a joke, or said something endearing, and she is smiling, and pulling back slightly. The summer awnings are out.

Here is a young man leaning against a tree. He may be smoking. He is jaunty and a little aggressive: the photographer has stood well back. An iron rod has been driven into the ground in front of him.

Here is a young woman, in a lovely gesture of happiness or embarrassment. She stands stiffly at the corner of a manicured lawn, across from a school or factory. It is the 1940s, as I can tell from the cars in the far background. It’s hard to see much, because the print is so small. (I am reproducing these about the size of the originals. They were mementos, and size matters.)

Here is what was probably their town, several storefronts around a cold lake scattered with ducks. A low winter sun casts the long shadow of a power line across a patch of bare ground.

Here is a tiny photograph (the original is one inch in height) of two men walking away from us, down a sidewalk. One has his hands clasped behind his back. Again the long shadows of the winter afternoon. The image was made with the cheapest of box cameras, and it is blurred around the edges. It must have been very precious: I imagine it as the only image of one of the men, the only picture of their life back then.

And here is a rock. It is in a well-traveled place, as I can tell from the tamped-down earth. But now there is no way to know why it was worth a photograph. I only know that it must have been meaningful to someone in the other photographs, or someone who owned them.

These, and a dozen more, came from one person’s collection, as I know because people and places recur in several images. The photos have lost the contexts that gave them value. And yet they have a pull on my imagination: the weak, persistent tug that comes from any picture of any person, made ever so slightly stronger by the knowledge that these people have been forgotten. Pictures like these don’t always sell on eBay, but many do, because there is a sizable market for other images of other people’s lives.

There is no easy way to stop this kind of reverie, no patch to staunch the floods of false nostalgia for people and places I don’t even know. Sympathy and curiosity well up in me. I want to reproduce all thirty-odd pictures in the packet, and begin to piece these people’s lives together. If I were a novelist I might work the pictures into a story. The same thing happens with fabricated collections, like Zoe Leonard’s Fae Richards Photo Archive. It hardly seems to matter what’s real and what isn’t. My interest is nothing more than an illness, a voyeurism, an apparently idle but adhesive concern with other people’s lives: a specific sickness brought on by photography.

I see these people’s lives as if they are covered with an old veil: they feel dank. Nostalgia itself is stale, and this is second-hand nostalgia. A breath of someone else’s life, breathed out into my mouth.

60 Third farewell: street photography. Farewell to all the photographs of street life, from Daguerre to Alfred Eisenstadt, Brassaï to Beat Streuli. From the more-or-less spontaneous, like Robert Frank’s The Americans, to the somewhat staged, like Ruth Orkin’s American Girl in Italy, to the completely contrived, like Robert Doisneau’s Kiss by the Hôtel de Ville.

This is two farewells, really. One is to the cliché that a street photographer can find the perfect instant. (Always the example is Henri Cartier-Bresson.) The other is to the cliché that a street photographer can find a type—a person, place or institution—and capture it once and for all.

Is there such a thing as a perfect instant, a moment when the randomness of ordinary life becomes a transitory tableau? To be successful, the composition of a street photograph has to possess a kind of insouciant imperfection, the token of reality and photography. Street photography like Cartier-Bresson’s depends on an interest in spontaneous gestures and “the precise organization of forms” in passing configurations, but I know those apparently spontaneous instants can never be anything more than examples of ideas I already have concerning spontaneity. Otherwise how would I rec...