![]()

Introduction

Tourism matters!

Geographical knowledge is more important than ever in an increasingly global and interconnected world. How can a graduate claim to be a learned scholar without any understanding of geography?

(Susan Cutter, President of the Association of American Geographers, 2000: 2)

Who we are is shaped in part by where we are. Human interactions with each other and the environment are rooted in geographical understandings, as well as the opportunities and constraints of geographical circumstance. Geographical approaches and techniques offer critical insights into everything from local land-use decisions to international conflict.

(Alexander Murphy, President of the Association of American Geographers, 2004: 3)

Tourism is widely recognised as one of the world’s most significant forms of economic activity. Despite concerns as to the effects of financial crises, climate change and the increasing costs of oil, tourism is forecast to continue to grow in the foreseeable future. In 2012, international tourist arrivals reached one billion for the first time, up from 25 million in 1950, 277 million in 1980 and 528 million in 1995 (United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO] 2012a).

International tourism is projected to nearly double by 2030 (UNWTO 2011a) from its 2012 figure. The UNWTO predicts the number of international tourist arrivals will increase by an average 3.3 per cent per year between 2010 and 2030 (an average increase of 43 million arrivals a year), reaching an estimated 1.8 billion arrivals by 2030 (UNWTO 2011a, 2012a). Upper and lower forecasts for global tourism in 2030 are between approximately two billion arrivals (‘real transport costs continue to fall’ scenario) and 1.4 billion arrivals (‘slower than expected economic recovery and future growth’ scenario), respectively (UNWTO 2011a).

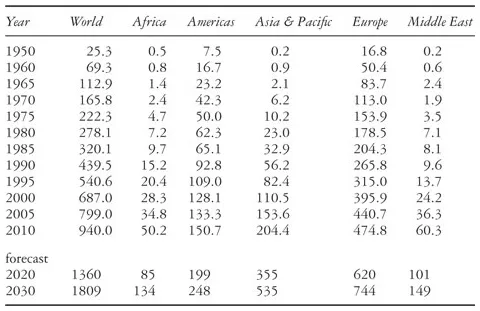

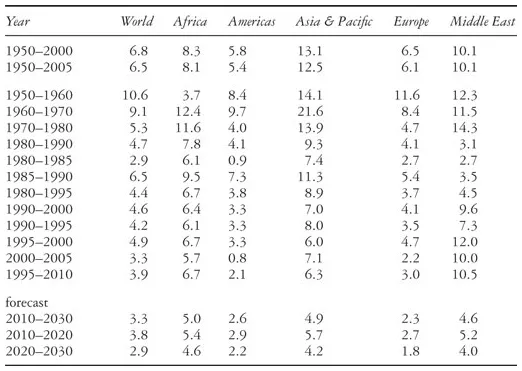

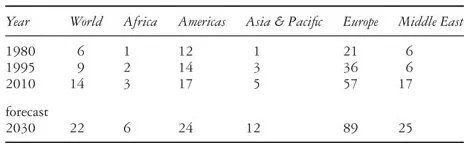

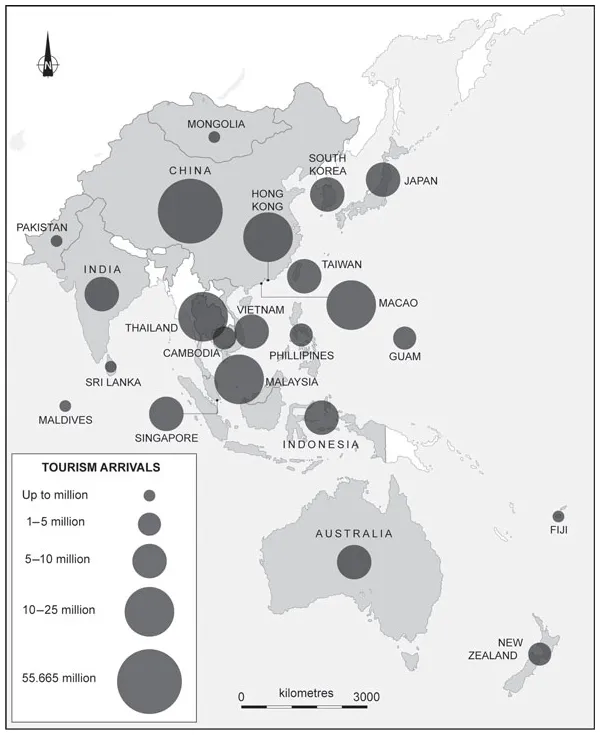

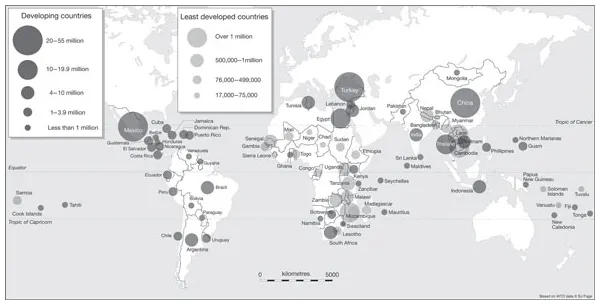

However, tourism, tourists and their impacts are clearly not evenly distributed over space or over time (Tables 1.1–1.4). Substantial differentiation occurs at a variety of international, regional and local scales. Most growth is forecast to come from the emerging economies and the Asia-Pacific, and by 2030 it is estimated that 57 per cent of international arrivals will be in what are currently classified as emerging economies, e.g. China, India, Malaysia (UNWTO 2011a, 2012a) (Figure 1.1). The UNWTO suggests that international tourism in emerging and developing markets is growing at twice the rate of the industrialised countries that have been the mainstay of the global tourism industry for nearly all of the past 50 years. Nevertheless, the international geography of tourism is changing. The UNWTO (2007) estimated that tourism is a primary source of foreign exchange earnings in 46 out of 50 of the world’s least developed countries (LDCs) (Figure 1.2). Between 1996 and 2006, international tourism in developing countries expanded by 6 per cent, by 9 per cent for LDCs, and 8 per cent for other low and lower-middle income economies (UNWTO 2008). Growth between 2000 and 2009 was also most marked in emerging economies (58.8 per cent), with their overall global market share growing from 38.1 per cent in 2000 to 46.9 per cent in 2009 (UNEP 2011). Table 1.5 indicates that although travel as an export activity has continued to grow over 2000–11 its relative proportion of total global export of services has declined, as with the developing countries, although its contribution to export activity in the LDCs has continued to grow over the same period. In addition, it should be noted that tourism’s relative importance in service exports varies by region, with it being considerably more significant for Oceania and Africa, a slight decline in Asia and a considerable decline in the Americas.

Table 1.1 International tourism arrivals and forecasts 1950–2030 (millions)

Table 1.2 Average annual growth in international tourism arrivals and forecasts 1980–2030 (%)

Table 1.3 International tourist arrivals by region per 100 population 1995–2030

(Sub)Region | 1995 | 2010 | 2030 |

Western Europe | 62 | 81 | 114 |

Southern/Mediterranean Europe | 47 | 71 | 103 |

Northern Europe | 42 | 63 | 80 |

Caribbean | 38 | 48 | 65 |

Central/eastern Europe | 15 | 25 | 47 |

Middle East | 9 | 27 | 47 |

Southern Africa | 9 | 22 | 46 |

Oceania | 28 | 32 | 40 |

Central America | 8 | 19 | 38 |

North Africa | 6 | 15 | 28 |

South-East Asia | 6 | 12 | 27 |

North America | 21 | 21 | 26 |

North-East Asia | 3 | 7 | 18 |

South America | 4 | 6 | 13 |

East Africa | 2 | 4 | 7 |

West and Central Africa | 1 | 2 | 3 |

South Asia | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|

Table 1.4 Generation of outbound tourism by region per 100 population 1980–2030

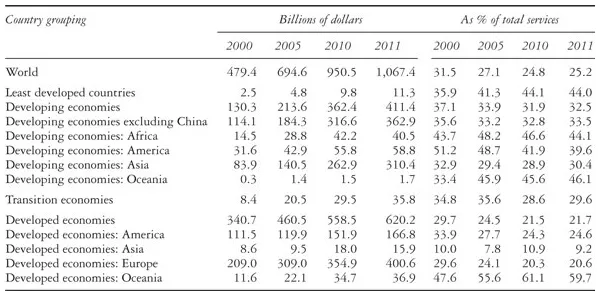

Table 1.5 Travel as an export activity 2000–11

Figure 1.1 Tourism in Asia

Source: Developed from UNWTO data.

Figure 1.2 Tourism in the developing world

Source: Developed from UNWTO data.

However, changes in the international tourism market will also be related to domestic holiday travel, as consumers can switch their travel plans not only between international destinations but also between domestic and international destinations. It is extremely important to remember that although international tourism is usually the primary national policy focus because of its trade dimensions and it is where many national tourism organisations (NTOs) focus their marketing attention (Coles and Hall 2008), the vast majority of tourism is domestic in nature and accounted for an estimated 4.7 billion arrivals in 2010 (Cooper and Hall 2013) (Table 1.6).

Table 1.6 Global international and domestic tourist arrivals 2005–30

| Year/billions |

2005 | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 |

Actual/estimated number of international visitor arrivals | 0.80 | 0.94 | 1.36 | 1.81 |

Approximate/estimated number of domestic tourist arrivals | 4.00 | 4.7 | 6.8 | 9.05 |

Approximate/estimated number of total tourist arrivals | 4.80 | 5.64 | 8.16 | 10.86 |

Approximate/estimated global population | 6.48 | 6.91 | 7.67 | 8.31 |

|

Tourism, as with other forms of economic activity, therefore reflects the increasing interconnectedness of the international economy. Indeed, by its very nature, in terms of connections between generating areas, destinations and travel routes or paths, tourism is perhaps a phenomenon which depends more than most not only on transport, service and trading networks but also on social, political and environmental relationships between the consumers and producers of the tourist experience. Such issues have clearly long been of interest to geographers. For example, according to Mitchell:

The geographer’s point-of-view is a trilogy of biases pertaining to place, environment and relationships. … In a conceptual vein the geographer has traditionally claimed the spatial and choro-graphic aspects as his realm … The geographer, therefore, is concerned about earth space in general and about place and places in particular. The description, appreciation, and understanding of places is paramount to his thinking although two other perspectives (i.e. environment and relationships) modify and extend the primary bias of place.

(Mitchell 1979: 237)

Yet despite the global significance of tourism and the potential contribution that geography can make to the analysis and understanding of tourism, the position of tourism and recreation studies within geography is perhaps not as strong as it should be (Gibson 2008; Hall and Page 2009; Hall 2013a). However, within the fields of tourism and recreation studies outside mainstream academic geography, geographers have made enormous contributions to the understanding of tourism and recreation phenomena (Butler 2004; Gibson 2008, 2009, 2010; Hall and Page 2009; Wilson 2012). It is therefore within this somewhat paradoxical situation that this book is written. Although the contribution of geography and geographers is widely acknowledged and represented in tourism and recreation departments and journals, relatively little recognition is given to the significance of tourism and recreation in geography departments, journals, non-tourism and recreation specific geography texts, and within other geography subdisciplines (Hall 2013a). Although, as Lew (2001) noted, not only do we have an issue of how we define leisure, recreation and tourism (see pp. 7–11), but also there is the question of what is geographical literature.

This book takes an inclusive approach and includes material published by geographers who work in both geography and other academic departments; material published in geography journals; and, where appropriate, includes discussion of literature that has a geographical theme and which has influenced research by geographers in tourism and recreation. In part the categorisation of literature into either ‘recreation’ or ‘tourism’ is self-selecting in terms of the various works that we cite. If one was to generalise, recreation research tends to focus on more local behaviour, often has an outdoors focus and is less commercial. Tourism research tends to look at leisure mobility over greater distances, often international, usually including overnight stay, and is more commercial. However, such categories are not absolutes and arguably, as the book indicates, are increasingly converging over time. This book therefore seeks to explain how the contemporary situation of the geography of tourism and recreation has developed, indicate the breadth and depth of geographical research on tourism and recreation and its historical legacy, and identify ways in which the overall standing of research and scholarship by geographers on tourism and recreation may be improved, including their contributions to new and emerging themes. We therefore adopt the working definition of Hall:

Tourism geography is the study of tourism within the concepts, frames, orientations, and venues of the discipline of geography and accompanying fields of geographical knowledge. The notion of tourism geographies describes the multiple, and sometimes contested, theoretical, philosophical and personal orientations of those who undertake tourism research from geographical perspectives.

(Hall 2013a)

This first chapter is divided into several sections. First, it examines the relationship between tourism and recreation. Second, it provides an overview of the development of various approaches to the study of tourism and recreation within geography. Finally, it outlines the approach of this book towards the geography of tourism and recreation.

Tourism, recreation, leisure and mobility

Tourism, recreation and leisure are generally seen as a set of interrelated and overlapping concepts. While there are many important concepts, definitions of leisure, recreation and tourism remain contested in terms of how, where, when and why they are applied (Poria et al. 2003; Butler 2004; Coles and Hall 2006; Coles et al. 2006). In a review of the meaning of leisure, Stockdale (1985) identified three main ways in which the concept of leisure is used, and that continue to influence contemporary understandings of the concept:

- as a period of time, activity or state of mind in which choice is the dominant feature;

- an objective view in which leisure is perceived as the opposite of work and is defined as non-work or residual time;

- a subjective view which emphasises leisure as a qualitative concept in which leisure activities take on a meaning only within the context of individual perceptions and belief systems and can therefore occur at any time in any setting.

Leisure is therefore best seen as time over which an individual exercises choice and in which that individual undertakes activities in a free, voluntary way. Leisure activities have long been of considerable interest to geographers (e.g. Lavery 1975; Patmore 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980; Coppock 1982; Herbert 1987). Traditional approaches to the study of leisure by geographers focused on leisure in terms of activities. In contrast, Glyptis (1981a) argued for the adoption of the concept of leisure lifestyles, which emphasised the importance of individual perceptions of leisure.

This allows the totality of an individual’s leisure experiences to be considered and is a subjective approach which shifts the emphasis from activity to people, from aggregate to individual and from expressed activities to the functions which these fulfill for the participant and the social and locational circumstances in which he or she undertakes them.

(Herbert 1988: 243)

Such an experiential approach towards leisure has been extremely influential. For example, Featherstone (1987: 115) argued that the meaning and significance ‘of a particular set of leisure choices … can only be made intelligible by inscribing them on a map of the class-defined social field of leisure and lifestyle practices in which their meaning and significance is relationally defined with reference to structured oppositions and difference...