![]() PART I:

PART I:

BACKGROUND MATERIAL![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

On January 1, 1990, the United States had a standing herd of 164.6 million head of the three principal red meat species–cattle, hogs, and sheep (USDA, “Situation and Outlook,” various issues).1

Supplying such vast amounts of meat is an amazing success story for the livestock production sector. The achievement is even more overwhelming considering that none of our principal meat species is indigenous to the hemisphere. Cattle, hogs, and sheep were either brought over from Europe with the early settlers or moved up from Mexico where they were introduced by the Spanish conquistadors and missionaries. The variety of names tells us of the ancestry—Angus and Hereford cattle, Yorkshire and Hampshire hogs – all are from the British Isles. The enormous red meats sector, the largest agricultural enterprise in terms of sales dollars, has developed from nothing over the past three centuries. And much of the growth, as we shall see, is far more recent, dating only to the end of World War II.

THE ROLE OF MARKETING

As much as the growth of the livestock sector is a success story for agronomists, animal scientists, and countless hard-working farmers and ranchers, it is also a testament to the marketing system. Without the simultaneous development of an effective and efficient marketing system, livestock would have remained on or near the farm. The large metropolitan areas could not have expanded as they did, and the world would be a much different place.

Despite the evident importance of the livestock and meat marketing system, it has a bad name with livestock producers. Many use the same vocabulary for marketing that is reserved for hoof-and-mouth disease and similar pestilence. In taking this view of marketing, the farmer travels in the rarefied company of Plato and Aristotle. Plato visualized marketing as little more than a necessary evil carried out by those whose “business is to remain on the spot in the market, and give money for goods to those who want to sell, and goods for money to those who want to buy.” For him, marketers “are, generally speaking, persons of excessive physical weakness, who are of no use in other kinds of labor.” (Figure 1-1).

While Plato’s views are surprisingly modern, Aristotle made the point even more bluntly. He regarded marketers as “useless profiteering parasites” and condemned their efforts as “unnatural, mercenary, exploitative and corrupting.” It would seem that many livestock producers are disciples of the Greek philosophers. For them, the societal and economic contribution is production. They view themselves, quite literally, as livestock producers. Exchange necessarily follows the production process. In earlier times, exchange involved barter; today, the universal exchange medium, money, is paramount.2

The idea of the exchange nevertheless remains unchanged. It is simply a transfer of ownership from seller to buyer, a process known as selling. Viewed in this way, selling is a purely mechanical activity, an exchange of money for whatever documents of legal ownership the system or the law requires. In such a world, the buyer is a necessary, if rather insignificant, intermediary who warrants a return only in proportion to this limited role. The producer is the center of this system, the source of wealth and happiness.

FIGURE 1-1. Plato [For Plato, marketers were persons of excessive physical weakness.] (Source: The Louvre)

As comforting as the livestock producer may find this view, it is as wrong and as antiquated as the notion that the sun revolves around the earth. What drives the capitalistic, free-enterprise system is not the producer but the consumer. The consumer ultimately decides who and what will be produced just as the vast gravitational power of the sun keeps the planets suspended in space. The producer who does not satisfy the dictates of the consumer disappears from the marketplace much like an errant “shooting star” in the heavens on a hot, late summer night.

Marketing

Serving the needs of consumers is the role of marketing. In the words of Professor Levitt’s classic article “Marketing Myopia,” the difference between marketing and selling is more than semantic:

Selling focuses on the needs of the seller, marketing on the needs of the buyer. Selling is preoccupied with the seller’s need to convert his product into cash, marketing with the idea of satisfying the needs of the customer by means of the product and the whole cluster of things associated with creating, delivering, and finally consuming it. (1960, p. 50)

Livestock producers share their myopic world view with other mass-production industries. Where technological change and lower unit costs for larger operations are prevalent, the urge to produce, produce, produce proves irresistible. Firms become product-rather than consumer-oriented, substituting their judgement of what the consumer wants for the comsumer’s true needs and desires. All too often the result is financial disaster; livestock producers talk with black humor of losing money per head but making it up on volume. Even the mighty, like General Motors, are not immune from market forces, as declining profits during the late 1980s demonstrated.

The resolution of this dilemma is marketing—the provision of services for which the consumer is willing to pay and on which a profit can be made. The remainder of this book describes marketing and its applications that help ensure the continued profitability of the red meats sector. Emphasis is placed on understanding the operations of the system with the idea that through knowledge comes the recognition of opportunities. To identify opportunities, it is necessary for each participant, each player, to understand his or her role and relationship with other participants and with the final decision maker, the consumer. In a system as large and complex as the red meats sector, this is a major undertaking.

Definition of Marketing

As intuitive as the concept may be, there is no universally accepted definition of the term, as the following passage makes clear.

It has been described by one person or another as a business activity; as a group of related business activities; as a trade phenomenon; as a frame of mind; as a coordinative, integrative function in policy making; as a sense of business purpose; as an economic process; as a structure of institutions; as the process of exchanging or transferring ownership of products; as a process of concentration, equalization, and dispersion; as the creation of time, place, and possession utilities, as a process of demand and supply adjustment; and as many other things. (Ohio State University 1965, p. 43)

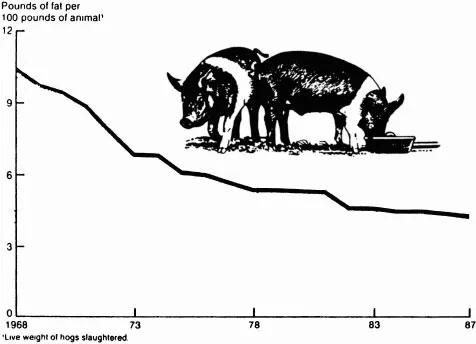

From these wide-ranging definitions, two interrelated insights can be generated. First, marketing is a very broad concept. Selling is but one small part of it, and some would argue that production itself can be subsumed as one aspect of marketing. This latter view is extreme perhaps, although it is clear that production must be attuned to the market. Volume should be high when demand is strong, and vice versa. Second, the product type must fulfill market needs. “Lardtype” hogs were in demand when animal fats were popular as cooking oils. Now that the oil market has largely been taken over by vegetable oils, the fatty hog is penalized in the market. Lard, rather than being a valuable product in its own right, is now largely a liability which must be cut away. In response to the changing market need, animal scientists have bred a leaner hog (as shown in Figure 1-2).

The notion that marketing is on approximately equal terms with production is a particularly galling one for livestock producers; however, their view does not recognize economic realities. In 1988, consumer expenditures for foods (excluding alcoholic beverages) originating on farms totaled over $460 billion. Of that sum, only about 25 percent went to farmers (USDA, ERS, Marketing Review, p. 1, Chartbook, Chart 128). The remainder, or 75 percent of food expenditures, went to pay for other services such as processing, transportation, and retailing. In total, this sum is known as the farm-to-retail price spread or, simply, the marketing margin.

A marketing margin of 75 percent means that, on average, for all products, consumers value marketing services by a ratio of three to one over the value of the raw product at the farm gate. That is, for every dollar spent on food, consumers pay an average of three times as much for the marketing service component of the product as they do for the basic ingredient. Of course, the proportions vary widely from product to product. The producer receives a large share of the retail price of lamb chops, a relatively unaltered product, while the value of wheat in a loaf of bread is said to be but a few cents. Similarly, away-from-home food purchases have higher margins than food prepared at home.

One of the basic tenets of a market or capitalistic economy is that in selecting among competitive products, the consumer makes rational choices, concerning prices, income, and the strength of preferences. Without considering all implications of this concept, known as consumer sovereignty, it can be applied to livestock marketing. In its basic form, what consumer sovereignty means is that consumers pay for livestock marketing services because they are valued. This brings us to a second aspect of marketing—the concept of value added.

FIGURE 1-2. Hogs Have Grown Leaner Over the Past 20 Years in Response to Changing Consumer Needs (Source: Duewer 1989, Fig. 1)

Value Added

A live steer in Colorado is worthless to a hungry vacationer in Miami. As trivial as this example may be, it does identify several major contributions of marketing. A product must be in the right place (Miami), form (rare steak), and time (6:00 p.m. today) to be useful to our traveler. Several components of the marketing system are involved in providing the necessary services: processing, aging, transportation, distribution, and preparation. Each of these activities adds value to the steer, just as the mining, forging, shipping, and assembling of a car add value to iron ore from the Minnesota taconite mines. Each of the contributors receives payment roughly in proportion to his contribution and ...