- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

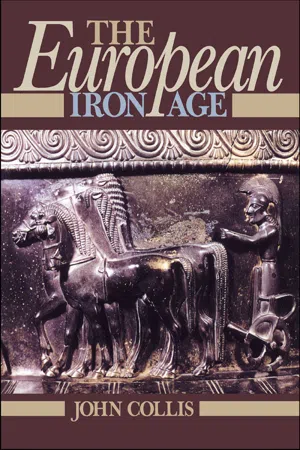

The European Iron Age

About this book

This ambitious study documents the underlying features which link the civilizations of the Mediterranean - Phoenician, Greek, Etruscan and Roman - and the Iron Age cultures of central Europe, traditionally associated with the Celts. It deals with the social, economic and cultural interaction in the first millennium BC which culminated in the Roman Empire.

The book has three principle themes: the spread of iron-working from its origins in Anatolia to its adoption over most of Europe; the development of a trading system throughout the Mediterrean world after the collapse of Mycenaean Greece and its spread into temperate Europe; and the rise of ever more complex societies, including states and cities, and eventually empires.

Dr Collis takes a new look at such key concepts as population movement, diffusion, trade, social structure and spatial organization, with some challenging new views on the Celts in particular.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The European Iron Age by John Collis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Arqueología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Ciencias socialesSubtopic

ArqueologíaCHAPTER ONE

Attitudes to the Past

Among the earliest surviving European literature is the poetry of Hesiod, notably his Works and Days, in which he describes the hard lot of the farmer— the labour involved in tilling the land to obtain the food needed for survival in a harsh and hostile world. Hesiod lived in the Age of Iron, but in happier days, in the Ages of Gold and Silver, food was plentifully available without the drudgery of farming: it only required gathering and eating. This idealised picture still plays a part in our schizophrenic view of the past and of ‘simple societies’, be it the concept of the ‘noble savage’, or what Sahlins has more scientifically documented as ‘the original affluent society’.

The opposite view of society is embodied in words such as ‘progress’ and ‘technological advance’, popularised in prehistoric terms by Christian Thomsen’s Three Age System. Who, Thomsen argued, would make axes of stone if they knew of bronze and iron? What had started as a classification of objects in the National Museum at Copenhagen rapidly became the basis for the chronological division of European man’s prehistory. Thomsen’s idea, coupled later with the concepts of evolution and of ‘the survival of the fittest’, reflected, if not originated, the self-satisfaction of late nineteenth-century West European society—the belief that it was technologically superior and therefore superior in all other respects to ‘less advanced’ societies both past and present. This reached its extreme form in the Germanic school of Kossinna whose views on the superiority of the German race formed one of the cornerstones of Nazi ideology.

If the extremist view of the Kossinna school was rejected by the majority of archaeologists, the modes of explanation were shared, except that ‘civilisation’ was a phenomenon which spread from the south-east rather than the north-west—ex oriente lux. Ideas spread by ‘diffusion’, an illdefined process which assumed the inevitability of the march of civilisation from one region to the next, and explained the movement of ideas in terms of pseudo-history—invasions and waves of migration of peoples across Europe. The revolution in dating by C14 destroyed the foundation of this approach for some aspects of the neolithic and Bronze Age periods, and in the literature appeared terms such as ‘independent development’ and ‘autonomy’ to explain the megalithic tombs of western Europe or the development of European copper and bronze metallurgy. But for the Iron Age at least neither ‘diffusion’ nor ‘autonomy’ were adequate explanations; it was clearly a combination of the two— ideas spreading from one area to another, with individual, unique reactions which produced a varied pattern of distinctive regional cultures.

The fashion today is to talk in terms of ‘culture change’, and to study the mechanics of how this happened in each society. Though each reaction may be unique, the process and mechanics which caused those changes still follow basic rules of explanation. Trade, for instance, can initiate change, but the objects exchanged, the way the trade was organised, the people who participated, and the reactions produced, though often similar, will appear in unique combinations in every case. The economy, the environment, technology, ideology and the social structure will combine in a unique system. In each case we cannot understand one aspect of the system without knowing something of the whole. To gain this knowledge, a study of the entirety of a society is the ideal, but there are practical limitations. The archaeological record represents only a wreckage of former societies in which the archaeologist tries to recognise patterns. Even the aspects of society which we might expect to survive do not always do so. Burials may for some reason not appear or settlements are difficult to locate. Added to this is the bias of the archaeologist. Too often our knowledge is derived from ‘treasure hunting’ by clandestine tomb robber and archaeologist alike, and the obsession of certain museums for objects of ‘art’, divorced from their context, has produced a hopelessly one-sided view of, for instance, the Etruscans. They are condemned for their second-rate art, but ignored for the unique development of their urban settlements. Scholarship too readily confines itself to one aspect of a society—its art, its sculpture, its architecture, its trade—but ignores the total context. Thus we have to study the process of urbanisation, or the economic impact of trade on Etruscan society, in terms of art history derived from gravegoods from tombs.

This book has the ambitious aim of studying such reaction and change in southern and central Europe in the first millennium BC. It was the period when European civilisation took its shape, with the appearance of the civilisations of the Greeks, Phoenicians, Etruscans and Romans, and, in more shadowy form, of the Illyrians, Celts and Germans north of the Alps. It starts in a period when Bronze Age Europe, though linked by trade within itself, was isolated from the Near East with the collapse of Mycenaean Greece at the end of the second millennium. We shall see how slowly, through the intermediaries of Phoenicia and Greece, a new network appeared along which trade objects, technology and concepts travelled, gradually embracing the Mediterranean, central Europe and, finally, Britain and Scandinavia. At the end of the period much of the area was united within a common entity, the Roman Empire.

My attitudes are those of a prehistorian viewing the world from central Europe, with a grounding in geography and anthropology rather than the traditions of Mediterranean archaeology. I am more concerned with those developments which are visible in the archaeological record than written sources, so that we can make direct comparisons between, for instance, the archaic states of Greece and central France. But such aims are not easy to achieve, as the existence of historical evidence has inevitably caused classical archaeologists to lean on these rather than on the archaeology. What did an early Greek state look like in spatial terms, what were the early towns really like—our views are too overlain by classical Greek concepts of what a city and city state was like. It causes problems of nomenclature. Classical archaeologists will call ‘kings’ and ‘tribes’ what anthropologists might call ‘chiefs’ and ‘chiefdoms’, bringing out our own innate prejudice of what these words mean. The whole of the archaeology is riven with such basic conceptual bias, and I will make no claims to have escaped it myself, but so that the reader can understand better the way in which the data we are considering has been collected in the past, and how different generations and types of archaeologists have attempted to arrange it in meaningful patterns, we must first discuss the basic attitudes from which the period can be viewed.

Population movement and ethnicity

Invasion and migration have been popular forms of explanation of culture change since the last century, and this has been especially true of the Iron Age, when we have documentary evidence that such migrations happened. However, it has often been too readily invoked, and there are problems with identifying it in the archaeological record even in documented cases. Groups often symbolise themselves in terms of material culture. We can identify pottery styles that are peculiarly Greek during the Geometric and Archaic periods. Though imitations do occur, and the pottery was traded, we can use it to identify Greek colonies, or the presence of Greek potters in Etruscan cities. The problem for the archaeologist is to decide what are the significant signals in the archaeological data. Is the provision of a horse with three tails on certain Iron Age coins in Britain something of overt significance to the users of the coins, was it merely a convention, or was there an underlyingrelationship between users of these coins of which even they were not immediately aware?

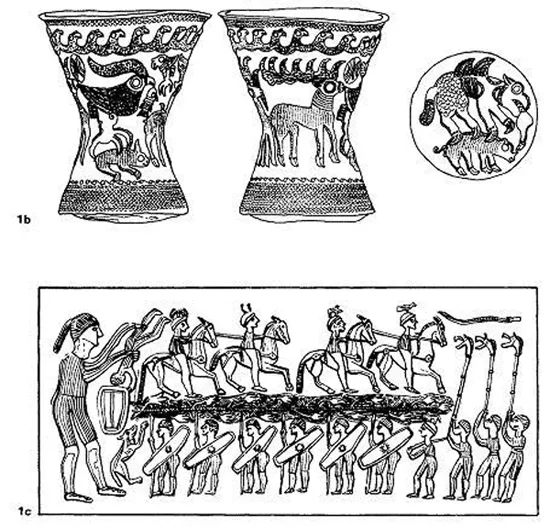

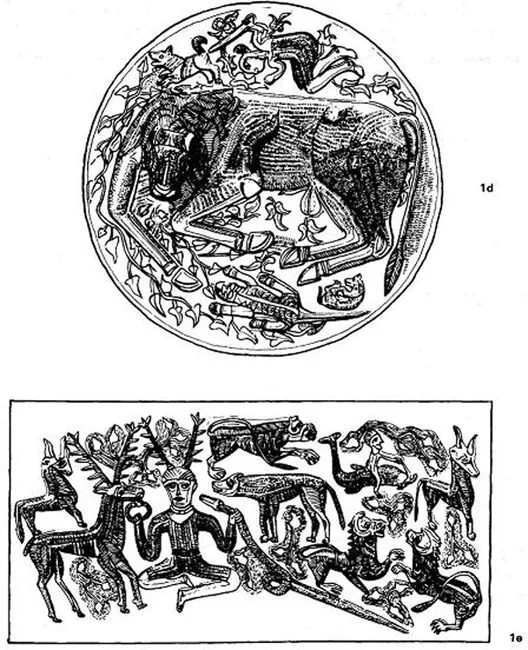

1 ‘Celtic’ metalwork

The Gundestrup cauldron (a) was found in a bog in northern Jutland in 1891. It had been dismantled and deliberately deposited, and, like many similar finds from Neolithic to Viking times in Denmark, it is probably a ceremonial or ritual offering. It consists of a number of silver plates decorated with repoussé ornament.

The style of the weapons, and especially the fact that the horsemen are wearing spurs, suggests a second or first century BC date. The art style is not local, and it was formerly thought the cauldron was an import from Gaul or more doubtfully from central Europe. The closest parallels, however, come from Romania, for instance the somewhat earlier silver cups from the burial at Agighiol (b), and it seems most likely that the Gundestrup cauldron was made in eastern Europe.

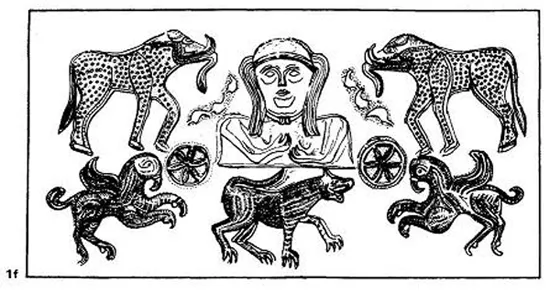

The iconography of the individual plates has attracted a wide literature, much of it fanciful. Some of the attributes of the individuals depicted are known from religious sculptures of Roman date from Gaul. Thus the antlered figure (e) is identified with the Celtic god Cernunnos. Some of the weapons (c)—the shields, the trumpet or carnyx—are known in La Tène contexts, but to go further and call this object ‘Celtic’ is to take archaeology beyond its limits. We cannot know the language spoken by the silversmith—it could have been Celtic, or German, or Thracian or Dacian.

He has taken a wide range of symbolism of different origins. The small figure slaying the bull on the central panel (d) reminds us of the later Persian cult of Mithras, the boy riding on the dolphin (e) appears in Greek mythology, the elephants (f) hint at ideas from further east, while the wearing of torcs found on several of the plates is something by no means confined to the Celtic world.

Scale: 1:3

The problems are most acute when we consider the Celts of central and western Europe. It is regularly assumed that we can equate ‘Celts’ with La Tène culture and La Tène Art. But what do we mean by ‘Celts’? People who spoke a Celtic language, or who were members of a political group who called themselves Celts, or a physical type (blue-eyed, fair haired, etc.), or should we not expect all these definitions to correspond exactly— did all people with La Tène Art speak a Celtic language; did all Celtic speakers have La Tène Art? Without care we can be led into nonsense. In most books on ‘Celtic Art’ the Gundestrup cauldron is illustrated, on the grounds that it depicts items of La Tène material culture (helmets, shields, trumpets), and Celtic deities such as Cernunnos the antlered god. But this object was manufactured in ‘Thracian’ or ‘Dacian’ Romania, and buried in ‘Germanic’ Denmark. The scenes mentioned do not make it ‘Celtic’ any more than the bull-slaying scene makes it ‘Persian’, or the elephant makes it ‘Indian’. Though we should be aware that items such as La Tène brooches may have an ethnic significance, we must be firmly aware of alternative explanations.

Diffusion

Diffusion implies the gradual adoption of new ideas and their general spread. It is a phenomenon which we can detect in, for instance, the spread of techniques of iron working, in the adoption of coinage, of urbanisation, of the potter’s wheel, and it lies behind the layout of this book. But it is a dangerous and misleading concept. On the one hand, it can lead to false assumptions in the source and direction of diffused ideas, such as the ‘hyperdiffusionism’ of Elliot and Perry which sought to derive all concepts of civilisation, even of Meso-American civilisation, from Egypt, views based on a number of fallacies, still, unhappily, perpetuated by Thor Heyerdahl in his Ra expedition. Secondly, it is in itself no explanation of why an idea spread, why it might be adopted by one society and not another, or indeed whether it necessarily played the same role in all societies. To take a concrete example: a type of knife or dagger may be in daily use by all members of society in the area where it is manufactured; it may be traded to a neighbouring society where its rarity makes it an item of prestige; it may be traded even further, into societies where it is considered so exotic that it is only used in ritual and ceremonial circumstances. Such changes of meaning can be documented in the modern anthropological record, we must assume that similar phenomena occurred in pre-history, as for instance the bronze vessels traded from Italy to southern Germany in the sixth century BC. In other words we must study the context of any object or innovation as it occurs in a society, and try to understand the role that it played and the message that it carried. We must also understand the social and economic context. The potter’s wheel will not be adopted if there is no tradition for making fine pottery or no way in which a specialist can be supported. Towns are not something which can suddenly spring up without the necessary social, political and economic institutions to support it. Diffusion is only a description, it does not tell us why.

The spread of the knowledge of iron working, especially the technology which allowed the production of functional tools and weapons, shows a classic pattern of diffusion, and other examples can be clearly identified in the archaeological record during the Iron Age. The ideas mostly emanated from the technologically and socially more advanced areas of the Near East and the east Mediterranean. We must, however, beware of assuming that all advances necessarily moved in a westward and northward direction. For instance, fortification techniques in the first century BC spread from Britain into neighbouring areas of the continent; bronze swords of early Hallstatt type may have spread in the seventh century BC from Britain towards central Europe. Indeed, in certain aspects central Europe was technologically more advanced at various periods in prehistory than the Near East, as in the production of long bronze swords at the beginning of the late Bronze Age, or the high-quality iron work which was being produced in the Alpine region in the second and first centuries BC.

However, the majority of technological innovations do have their origin in the Near East. The use, for instance, of the potter’s wheel is something we see appearing in Greece around 1050 to 1000 BC, and then appearing alongside other evidence of Greek contact in central Italy in the period about 750 to 700 BC. Thence it spread into northern Italy by around 700 BC, and we find its first introduction into central Europe at the major trading centres of the Heuneburg and Mont Lassois around 550 to 500 BC. Not until the end of the second or beginning of the first century BC did this new technology reach southern England, and other areas such as northern Britain and Scandinavia were not to adopt the potter’s wheel until the Roman Iron Age, if not even later. In this particular case the adoption of a more advanced technology was hindered by the low level of economic development in various societies, which did not have the institutions which could support specialised industries. It is also connected with the organisation of society, especially the presence of an elite clientele who could form a market for highquality goods

. The most far reaching and complex of these diffusion patterns is that associated with the socalled ‘orientalising’ process visible in the artistic styles of the Mediterranean and central Europe. This was connected with the trade patterns which emanated from the developing civilisations of the Near East, Greece, North Africa and Italy. It is characterised by the adoption in local art forms of floral motifs, such as the lotus bud and palmette, and animal motifs whose origin can be seen in the Near East. Most obvious are the various mythical beasts, often mixtures of various animals, or animals and humans, such as the sphinx, the winged horse, centaurs, fawns, chimaeras and gryphons. With these ideas also moved technological information, especially in the production of beaten bronze metalwork on which many of these artistic motifs are depicted. But artistic change may reflect more fundamental changes within society, and we find that the same creatures appear in myths explaining the nature and structure of Greek society—such as the role of the sphinx in Thebes, or the minotaur in Athens—to confirm the dominant position of certain of the leading families.

Trade

Trade falls into three main categories: longdistance, inter-regional, and local. It is the longdistance trade that is easiest to detect in the archaeological record because foreign and exotic goods are readily identified from more local objects. By inter-regional is meant the exchange of goods often over long distances, but within a similar cultural milieu, and which may involve objects which are similar, at least in outward form, to local products. In the case of pottery, for instance, it may only be the composition of the clay which betrays a foreign object.

The motivations for trade varied, and, though there is obviously a general economic context within which trade is going on, to understand the nature of prehistoric trade we must try to identify which sectors of society were engaged in the trade, and what their motivations might have been. Within the general economic context, it is the lack of basic raw materials which will motivate trade in the first place. Certainly by the end of our period we can identify societies which cannot exist without trade in some form or another, not merely for raw materials, but even for their basic food supplies, and into this category come some of the Greek cities like Athens, and later, Rome. The major cities of the Near East, especially those of the Mesopotamian Plain, were equally reliant upon trade for their very existence; although food was no major problem, all other raw materials especially metals and wood had to come from outside the Mesopotamian Plain. But the pattern is not quite as simple as one might imagine, as often the trade was not controlled by the large city states and empires where the need and the wealth resided, nor necessarily in the source areas of the raw materials. It is not uncommon for peoples peripheral to the main trade route to gain control of it and to act as middlemen—a characteristic we find in the trade networks of both the Greeks and the Phoenicians.

This brings us to the question of who within society was engaging in trade. Trading is an activity which is carried on by individuals for two reasons— either to acquire wealth, or to acquire status. In societies where hereditary power is based upon land ownership, as in the classical societies of Greece and Rome, an independent class of merchants who are acquiring wealth by trade and industry can represent a threat to the ruling class, and various alternative strategies have been adopted in the past to counteract this problem. In some societies, for instance, external trade is left in the hands of foreign merchants, who must pay tolls to the state, and who may be restricted in their movements to specific ports or trading centres, but who, by being foreigners, represent no threat to the power structure within the society. Foreign influences themselves can be capable of undermining society, and in certain cases, as with the Phoenician sites of Tyre and Sidon, neighbouring powers such as Assyria were willing to leave them independent, so that all foreign trade could be channelled through them—the so-called ‘ports of trade’. China ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Chapter One: Attitudes to the Past

- Chapter Two: The Old Order

- Chapter Three: Reawakening in the East

- Chapter Four: The Trade Explosion

- Chapter Five: The Tide Turns, 500–250 BC

- Chapter Six: The Economic Revival

- Chapter Seven: The Roman Empire and Beyond

- Notes and Bibliography