eBook - ePub

Iron Age Communities in Britain

An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC until the Roman Conquest

- 752 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Iron Age Communities in Britain

An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC until the Roman Conquest

About this book

Since its first publication in 1971, Barry Cunliffe's monumental survey has established itself as a classic of British archaeology. This fully revised fourth edition maintains the qualities of the earlier editions, whilst taking into account the significant developments that have moulded the discipline in recent years. Barry Cunliffe here incorporates new theoretical approaches, technological advances and a range of new sites and finds, ensuring that Iron Age Communities in Britain remains the definitive guide to the subject.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Iron Age Communities in Britain by Barry Cunliffe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Weltgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

GeschichteSubtopic

WeltgeschichtePart I

Introduction

1

The beginnings of Iron Age studies

It is not proposed in this chapter to indulge in an extensive and somewhat incestuous examination of the growth of Iron Age studies in Britain simply for the sake of conventional completeness, nor for the specious exercise of holding up to ridicule the views of previous generations who have written on the subject. But some idea of how patterns of thought have developed to their present state is essential, not only because the models of the past have necessarily influenced the interpretations, and indeed the gathering, of the facts, but also because current views may tend to overreact against established dogma.

That an ‘Iron Age’ existed at all was suggested by the Danish archaeologist C.J. Thomsen, in a book published in 1836, but it was not until G. Ramsauer’s excavation at Hallstatt, between 1846 and 1862, and the discoveries made at La Tène in 1858, that any permanent chronological divisions could be made. Then followed several schemes: C. Schumacher divided the Hallstatt material into four groups: A (1000–800 BC), B (800–700), C (700–600) and D (600–500); while G.O.A. Montelius, working on French discoveries, propounded three periods for the La Tène epoch: I (400–250 BC), II (250–150 BC) and III (150–1 BC). Subsequently P. Reinecke, J. Déchelette, R. Viollier and others evolved finer and differing classifications influenced by new material and by regional considerations. It was against this background that the British finds came to be interpreted.

The first half of the nineteenth century saw the gradual amassing in museums and private collections of quantities of Iron Age finds, usually tools, weapons and art objects, brought together by casual discovery and by the pilferings of the early barrow diggers like the Revd E.W. Stilling- fleet, who managed to excavate between 100 and 200 barrows of the Arras culture between 1815 and 1817. Barrow-sacking in high Victorian style continued to produce Iron Age finds from east Yorkshire throughout the century, but ended with the carefully observed researches of J.R. Mortimer, published between 1895 and 1911. Outside Yorkshire the British Iron Age was not susceptible to this type of acquisitive excavation, and the bulk of the finds continued to be made by accident. The emphasis of the early collectors was naturally enough upon works of art. In 1857, the year before the discovery at La Tène, J. Thurnham listed objects of ‘Late British Art’, and even six years later, when Sir Wollaston Franks illustrated a series of La Tène objects at the British Museum, he was forced to refer to them as ‘Late Keltic’ for want of a more precise terminology. With the development of the Continental Hallstatt and La Tène classifications after 1872, however, British archaeologists were provided with a simple system with which to compare their own material; thus gradually the European nomenclature gained acceptance.

In parallel with the early archaeological discoveries linguists were developing theories about the peopling of Britain. Most influential among them was Sir John Rhys, the Jesus Professor of Celtic at the University of Oxford. In 1882 the first edition of his seminal book Early Britain: Celtic Britain was published (with subsequent editions in 1884 and 1904) in which he argued that Goidelic Celts from the Continent spread into southern Britain and later Ireland, to be replaced in Britain by a second invasion, this time of Brythonic Celts. The two invasions accounted for the two main divisions of Celtic speech in the British Isles. Rhys’ model, which owes much to Edward Lhuyd (1660–1709), provided a structure against which the archaeological material was to be compared.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, excavations began to be mounted on occupation sites and hillforts in an attempt to understand the people and their way of life. This was a marked advance on the somewhat sterile art-historical approach. Between 1857 and 1858 the first large-scale excavation of a settlement site was undertaken at Standlake in Oxfordshire by Stephen Stone, in advance of gravel-working. Altogether 134 pits were exposed, and were duly reported to the Society of Antiquaries. Ten years after the Standlake excavation, a similar area of Iron Age settlement was cleared at Highfield, Fisherton, near Salisbury. At both sites it was naturally the more obvious features such as pits and gullies that were examined, but quantities of occupation rubbish were recovered and gradually the nature of Iron Age peasant settlement began to force itself on the attention of an archaeological world hitherto blinded by the quality of a few art objects.

The next major advances were made by General A.H.L.F. Pitt Rivers. Following a meticulously recorded but relatively small-scale excavation at the Caburn, Sussex, in 1877–8, during which he had sectioned the ramparts as well as clearing out pits (Figure 1.1), he finally turned his attention to his Cranborne Chase estates, where between 1880 and 1890 he totally excavated the two settlements of Woodcuts and Rotherley Down, and sampled the hillfort at Winklebury, Wilts. (Pitt Rivers 1887, 1888). His work was of an exceptionally high standard and was published in a detailed manner never before achieved. It emphasized two things above all: the value of considering the commonly occurring debris of occupation as the principal means by which people and their lives could be reconstructed, and the importance of large-scale regional studies.

The last decade of the nineteenth century saw the unremitting development of these two principles. In Devon the Dartmoor Exploration Committee was set up in 1894, and within the first ten years of its existence had examined twenty sites and excavated nearly 150 hut circles, under the direction of S. Baring-Gould. At the turn of the century Baring-Gould extended his interests into south-west Wales with the excavations of the hillforts of St David’s Head and Moel Trigarn. Other hillforts were now receiving attention: excavations at Worlebury in Somerset were finally published in 1902 at the same time as the first adequate consideration of Bigbury in Kent.

Pitt Rivers’ dictum of large-scale excavation was extended into Somerset by his assistant H. St George Gray who, in conjunction with A. Bulleid, began the famous excavations at the so- called Glastonbury Lake Village in 1892, work which was to continue until 1907 and was finally published in 1911 and 1917 (Coles, Goodall and Minnitt 1992). Nor were regional studies neglected: in Wiltshire Benjamin Cunnington and his wife Maud undertook annually an impressive series of excavations: Oliver’s Camp (published 1908), Oare (1909), Knap Hill (1911), Casterley Camp (1913) and Lidbury (1917), but the most famous of all was their work at All Cannings Cross between 1911 and 1922, finally published in 1923. A two-year programme at Hengistbury Head started in 1911 (Bushe-Fox 1915); excavations began on the Somerset village of Meare under the direction of Bulleid and Gray in 1910, and between 1908 and 1912 (Figure 1.2) the cave of Wookey Hole was carefully examined (Balch 1914) (Figure 1.3).

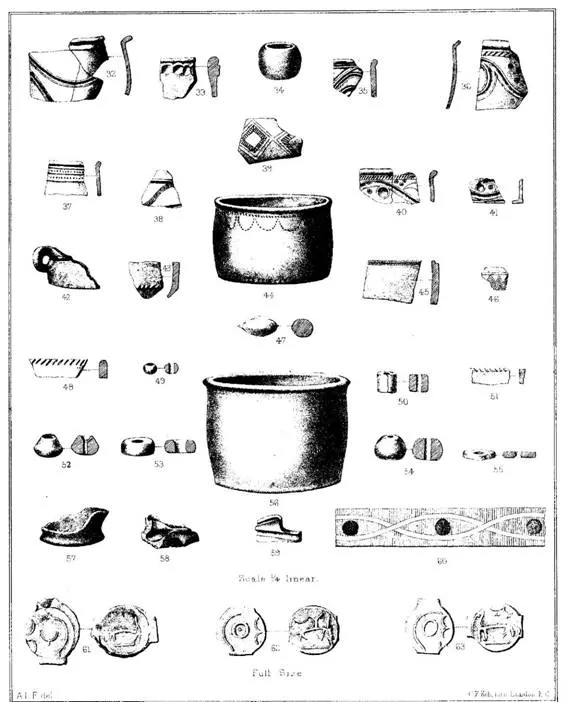

Figure 1.1 Antiquities from Mount Caburn, Sussex (source: reproduced from Pitt Rivers 1881, pl. XXV).

Figure 1.2 Excavations at Meare Village East, Somerset, August 1935. St George Gray stands on the left (photograph: Somerset County Museum Service and Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society).

After the First World War, discoveries continued to be made and reported in increasing numbers: Hallstatt style pottery from Eastbourne, excavations at Abington Pigotts in Cambridgeshire, Park Brow in Sussex and Fifield Bavant in Wiltshire, all in 1924, and excavations at Swallowcliffe Down and Figsbury in Wiltshire in 1925. Thus by the year of publication of the second edition of the British Museum’s Guide to the Antiquities of the Early Iron Age (Smith 1925), a vast collection of material – common artefacts – had been amassed to redress the balance of the collectors’ pieces, and it is much to the credit of Reginald Smith, the Guide’s compiler and a Deputy Keeper of the Museum, that so much was said of these common things. Iron Age communities were at last being considered in all their aspects.

With the rapid increase in the bulk of the potential evidence, classifications and interpretation developed in parallel. The turning point was undoubtedly the discovery in 1886 of the Belgic cemetery at Aylesford and its publication four years later by A.J. (later Sir Arthur) Evans (Figure 1.4). The report was an outstanding contribution to Iron Age studies: in it Evans characterized the Aylesford people, showing their differences from the inhabitants of the rest of Britain, and tracing their immediate origins to northern France and ultimately back through the Marnian culture to the Illyro-Italic cultures of the fifth century. After a masterly consideration of the metalwork, he concluded that the Aylesford cemetery dated to after 150 BC and went on to link the Aylesford culture to the statement by Caesar that the coastal parts of Britain had been settled by Belgic invaders. In spite of a somewhat cursory treatment of the archaeological evidence by T. Rice Holmes in his famous work Ancient Britain and the Invasions of Julius Caesar (1907), Evans’ conclusions were widely accepted and further consolidated by Reginald Smith’s publication of the rich Belgic grave groups from Welwyn in 1912. Some geographical precision was given to the distribution of the Aylesford culture by Sir Cyril Fox in his Archaeology of the Cambridge Region (1923), but he retained reservations about its exact identity. New discoveries of a major cemetery at Swarling, Kent, in 1921 and its subsequent publication by J.P. Bushe-Fox in 1925, however, firmly established the Aylesford–Swarling culture as an intrusive element but refined Evans’ dating, showing that there was nothing found with the burials earlier than 75 BC.

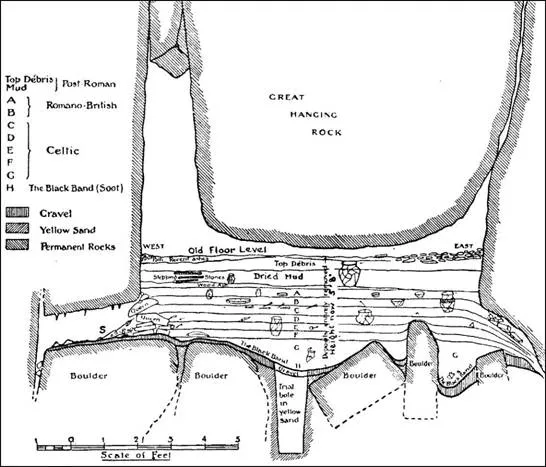

Figure 1.3 Stratified Iron Age deposits at Wookey Hole, Somerset (source: reproduced from Balch 1914, pl. IX).

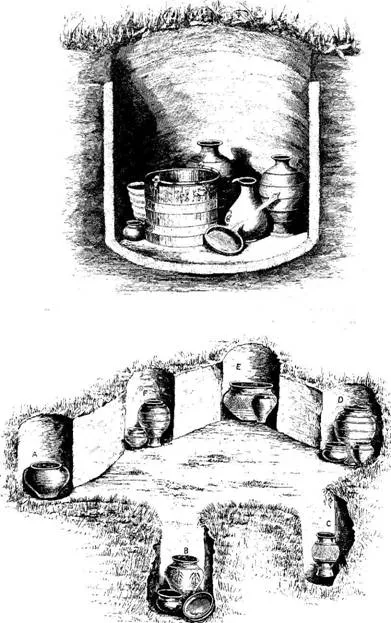

Figure 1.4 The Aylesford cemetery, Kent (source: reproduced from A.J. Evans 1890, Figures 1 and 4).

With the demonstrable reality of a Belgic invasion and the growing awareness of the intrusive nature of the Arras culture represented in the La Tène style barrow cemeteries of Yorkshire, a climate of opinion arose in the first two decades of the twentieth century which considered invasion to be the principal, and sometimes the sole, cause of change. Such views were well rooted in the ideology of Victorian imperialism: after all, nineteenth-century colonial history could produce many striking parallels. In 1912, J. Abercromby suggested that the so-called Deverel–Rimbury urns were introduced into Britain from the Lausitz culture area of central Europe between 700 and 650 BC, and ten years later O.G.S. Crawford developed the invasion theory further by suggesting that the immigrants were Goidelic Celts, but had them arrive a century or so earlier, bringing with them weapon-types which characterized the Late Bronze Age. H. Peake elaborated the idea still further in The Bronze Age and the Celtic World (1922) in which, arguing principally from the evidence of the swords, he proposed three invasions: the first about 1200; the second about 900, bringing much of the Deverel–Rimbury assemblage; and the third about 300 BC, representing the intrusion of the Brythonic Celts, after iron and elements of the La Tène culture had already arrived as the result of trade.

While the Abercromby–Crawford–Peake invasion hypothesis was evolving, discoveries were made at Hengistbury Head and All Cannings Cross of assemblages of pottery containing furrowed haematite-coated bowls and coarse finger-impressed wares. The Continental Hallstatt analogies were at once evident. Moreover, the association at All Cannings Cross of haematite pottery, finger-impressed wares like Deverel–Rimbury types and bronze implements suggested to some that the All Cannings Cross community represented an intrusive population, which Peake readily ascribed to his second invasion. Maud Cunnington, the excavator of All Cannings Cross, summed up the situation in the following words:

A big movement of people northwards on the continent, whether the incentive was search for better farming land, or mere love of adventure, was bound sooner or later to make itself felt in Britain. This invasion is not likely to have come about as a single incursion but… by a long continued series of small incursions and colonisation.

(1923, 22)

So by 1925 linguistics, implement typology, settlement archaeology and historical parallels were in broad agreement: a complex of Late Bronze to Early Iron Age invasions led to the All Cannings Cross style of culture before the middle of the first millennium; an incursion from the Marne gave rise to the Yorkshire barrow culture in the third century; and the Belgae colonized the south-east of Britain in the first century.

The discoveries of the next five years were, however, to complicate the issue. Several new hill- forts were being excavated, including Ham Hill, Somerset (1925–7); Chun, Cornwall (published 1927); the Caburn, Sussex (published 1927); Bury Hill, Glos. (published 1929); the Trundle, Sussex (published 1929 and 1931); and St Catharine’s Hill, Hants. (excavated 1925–8 and published 1930). New groups of finds from occupation sites at Findon Park, Sussex, and Scarborough, Yorks., were published in 1928, while in the previous year Fox’s paper on La Tène I fibulae had appeared. In this atmosphere of rapid new discovery Christopher Hawkes produced three important papers: the first, entitled ‘The earliest Iron Age culture of Britain’, appeared in the St Catharine’s Hill report (Hawkes, Myres and Stevens 1930); the second, ‘Hill forts’, was published in Antiquity for March 1931; while the third, written with Gerald Dunning and called ‘The Belgae of Gaul and Britain’, appeared in the Archaeological Journal in the same year. These three papers totally altered the direction of thought on the Iron Age and paved the way for the next three decades of constructive study. Taking account of all the evidence at the time available, a new scheme was proposed as a logical development of the invasion hypothesis bandied about somewhat loosely in the previous twenty years. Hawkes visualized a massive series of migratory movements among the Celts in central and northern Europe, beginning in the seventh century or before. ‘It reached its height in the sixth century, when those groups who crossed over to Britain became our principal Early Iron Age immigrants.’ Other Celts in the Late Hallstatt stage of culture who were displaced from France also migrated to Britain.

Thus was completed our widespread agglomeration of Late Hallstatt immigrant groups, predominantly Celtic in blood, but inevitably including other racial elements out of the melting pot of contemporary Europe. Fusing here and there with the Late Bronze Age peoples, they established Iron Age civilisation all over the south and south east of Britain… The main block of their area remained in their undisturbed tenure till the first century BC, and their civilisation, though essentially of Hallstatt character, soon began to absorb influence from the La Tène culture across the Channel. Thus it really requires a name of its own: here we shall be content to call it ‘Iron Age A’, and the succeeding immigrant cultures ‘Iron Age B’ and ‘C’. The former, in the south west and north east, merely bit into its fringes; it was only the latter, brought by the Belgae, that superseded it in its real home, and in some districts, notably east Sussex, it was never superseded at all till the Roman conquest.

(Hawkes 1931, 64)

Hawkes, then, visualized a complex folk movement impinging in stages on south-east Britain in the sixth century, giving rise to his Iron Age A culture (Figure 1.5). Life was at times troubled and great hillforts had to be built, ‘for as there was no doubt constant tribal bickering, warfare must always have been liable to spring from the background into the foreground of existence’ (p. 76). Early in the fourth century a new invasion took place: La Tène peoples from Spain, the Atlantic seaboard and Brittany thrust their way into Cornwall (an idea put forward by E.T. Leeds in 1927, following his excavation at Chun Castle) and spread into Devon, Somerset, Dorset and the Cotswolds, ‘absorbing or driving out such Iron Age A people as they found, and superseding their settlements’ (Hawkes 1931, 77). These were the Iron Age B people: Spanish La Tène I fibulae, distinctive decorated pottery and historical contacts connected with the tin trade could be quoted in support of this view. In this country the south-western Iron Age B immigrants built great multivallate earthworks and lived in the Somerset lake villages, making highly ornamented pottery. The northern counterpart to the south-western B invasions came in the third century with the incursion of a band of immigrants from Gaul, spreading from Yorkshire to the Cambridge region. These northern Iron Age B peoples eventually linked up with the southwestern invaders by means of the Jurassic Zone, encircling the A people of the south-east.

The third major series of invasions, giving rise to Iron Age C, began in about 75 BC with an influx of Belgic tribesmen from northern...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Space and time

- Part III Themes

- Part IV Systems

- Appendix A Pottery

- Appendix B A note on radiocarbon dating

- Appendix C List of principal sites

- Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Index