![]()

Part 1

Architecture theory,

dendrology, sociology

and landscape

archeology

![]()

Chapter 1

Theoretical landscapes

On the interface between architectural

theory and landscape architecture

Kari Jormakka

Introduction

Summarizing the remote pages of Pierre Boitard's Manuel de l'architecte des jardins, Gustave Flaubert divides gardens into:

(a) the melancholy and romantic, distinguished by immortelles, ruins, tombs, and ‘a votive offering to the Virgin, indicating the place where a lord has fallen under the blade of an assassin’

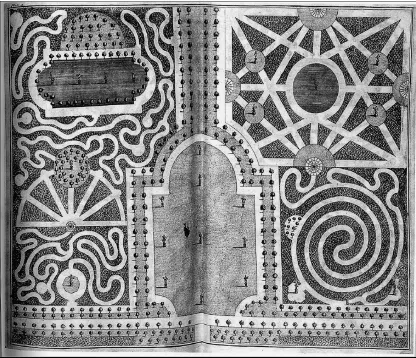

Figure 1.1 A garden maze. From Batty Langley, Practical Geometry, applied to the Arts of Building, Surveying, Gardening, and Mensuration. London: W. & J. Innys, J. Osborn and T. Longman, B. Lintot et al., 1726.

(b) the terrible, featuring overhanging rocks, shattered trees and burning huts

(c) the exotic, with Peruvian torch-thistles that ‘arouse memories in a colonist or a traveler’

(d) the grave, offering a temple to philosophy

(e) the majestic, populated by obelisks and triumphal arches

(f) the mysterious, composed of moss and grottoes

(g) the dreamy, centered on a lake

(h) the fantastic, where the visitor, after meeting a wild boar, a hermit and several sepulchres, will be taken in an empty barque into a boudoir to be laved by water-spouts. (Flaubert 1971: 59–60).1

In mapping a site streaked with aporias and ruptures, Flaubert's categories capture the heterotopic logic that characterizes gardens and, by extension, landscape architecture in general. This lack of hierarchical order may be the reason why many writers, such as John Dixon Hunt, have felt that landscapes have not been as fully theorized as architecture (Hunt 1992). What I attempt to suggest below is that heterotopic thinking, far from being a handicap, is in fact one of the major resources of landscape architecture and something that also enriches architectural theory.

In the Order of Things, Michel Foucault appropriates the medical concept of ‘heterotopia’ to describe contradictory conceptual schemes which make it impossible to name this or that thing because they tangle common names and destroy syntax in advance, ‘and not only the syntax with which we construct sentences but also that less apparent syntax which causes words and things to hold together’. In their madness, however, heterotopias also have the more positive function of exposing the equal relativity and arbitrariness of every alternative classification (Foucault 1970). In the essay ‘Of other spaces’, Foucault approaches the term ‘heterotopia’ from another angle. Instead of conceptual schemes, he claims to address the real physical environment. Heterotopias are described as real existing places that are ‘formed in the very founding of society’, as part of the presuppositions of social life. They are ‘counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted’. Heterotopias must therefore be contrasted with the ordinary, dominating, real sites but also distinguished from utopias, places which also represent society in perfected or inverted form but do not actually exist. Furthermore, heterotopias have the curious property of being in relation to all the other sites in such a way as to suspect, neutralize or invert the set of relations that they happen to designate, reflect or mirror (Foucault 1993: 422).

Heterotopias

Among his countless examples of heterotopias, Foucault includes the oriental garden because it represents another site in miniature. Other reasons could also be named for seeing gardens as heterotopias: they combine elements of nature and architecture only to undermine both. A familiar strategy of garden architects involves subverting the natural characteristics of things by forcing natural materials into shapes and states they would not normally take. In the garden of Villa Garzoni at Gollodi, for example, cypresses ‘twisted and stretched, now jesting, now serious’, taking the form of a tower, a ship, a pear, or an angel (Ponte 1991: 182).2 The intersections of Platonic forms with ephemeral nature, animals with plants, eternity with transience, figurality with abstraction allow for no totalizing discourse. Fountains are another case in point: the most primitive of all natural elements, water, is harnessed to deny the most basic fact of earthly existence, gravity. Elaborate hydraulic contrivances at the Villa d'Este, Tivoli, Italy, even transform water into music, the most unnatural of all cultural creations of man. Every garden, no matter whether formal or informal, no matter how conventional or unspectacular, is ultimately an artifact and as man-made nature an implicit criticism of the role of the creative subject itself, man as natura naturans collapsed with natura naturata.

On another scale, too, the culture of gardens is one of inversions. By letting an Egyptian pyramid in the New Garden at Holy See in Potsdam serve as an ice cellar and housing the kitchen in a Roman temple, Carl von Gontard and Carl Gotthard Langhans were not only being sacrilegious but also revealed the fragility of architectural theory, of assignments of programme, of typological categories and of fictions about functional form. Such questioning results in a heterotopic universe that exists in another place and time than ours. It is not without justification that Yves Bonnefoy describes the Désert de Retz as a place of mysteries, ‘at the antipodes of ordinary life’ (Hunt 2008: 244).

Similarly, the garden of Stowe, with its thirty-eight monuments ranging from a temple of Bacchus to Gothic churches, inspired one visitor to state that ‘the owner and the creator of this superb solitude have even had ruins, temples and ancient buildings built here, and times as well as places are brought together in the splendor that is more than human’ (Baltrusaitis 1995: 212).

However, horticultural heterotopias are not limited to the assortments of oddities in Romantic gardens. Renaissance gardens occasionally question fundamental temporal divisions. The garden of the Villa Lante at Bagnaia, for example, can be read as a narrative that relates the carefully orchestrated transformation of trees into columns and the materialization of voids as columns. Simultaneously old and new, originary and derivative, the elements in the garden assert and deny their own rhetorical mode. Gardens can also undermine the authority of architecture. In Vauxle-Vicomte, Le Nôtre achieved the astounding feat of destabilizing the very image of stability, the castle, which apparently changes location as new terraces are gradually revealed to the visitor.

Contradictions

In such exercises in contradiction, garden designers have often followed the credo of Antoine de Ville who argued in 1666 that the gardener must work like God, ‘who has ordered and arranged things quite contrary to their qualities in such proportion that they continue without destroying each other’. This way, gardens also reveal and celebrate the essential nature of the world, composed as it is ‘of opposing parts, without which nothing can survive’. According to de Ville, trees and plants are jealous one of the other, as are rational and animal creatures, in the same way as the parts of a machine or of a system of fortification. This vital principle of ‘contrariety’ or ‘discord’ must not be suppressed but rather regulated by art (Vérin 1991: 136).

Contrariety may not impossibly be one of the essential characteristics of gardens. At the most basic level, this applies to the relationship between the garden and its surroundings. As a utopian ideal, paradise has always been represented by that which was scarce or absent, the other. In the south, the paradise was a grove or an oasis, while in the north, where forested landscapes existed, the exceptional scene was the absence of trees, as evidenced by the fact that the Anglo-Saxons used the word for meadow to signify paradise. Thus, as J. B. Jackson has pointed out, there are in the west two distinct garden traditions, that of the enclosure and the artificial forest and that of the clearing and architectural forays (Jackson 1980). If the former is reflected in the Edenic myths of Gilgamesh or Adam, the latter is portrayed in the creation myths of the north, such as the Finnish Kalevala.

The contrariety of garden architecture leads to and results from a certain multiplicity in the corresponding theory. In the third part of Aesthetics, G. W. F. Hegel declared that the art of garden design, like dancing, is an ‘incomplete art’. The incompleteness of gardening derives from its effortless combination of various arts and sciences, such as botany, engineering, architecture, zoology, hydraulics and musical theory, resulting in the irregular multiplicity of mazes and bosques, bridges over stagnant water, surprises with Gothic chapels, temples, Chinese houses, hermitages and so on. Hegel compares such hybrid assemblages to hermaphrodites, cross-breeding and amphibians which only manifest the impotence of nature to maintain essential border lines. He insists that while gardening can deliver pleasant, graceful and commendable effects it will always fall short of actual perfection (Hegel 1955: 262).

Furthermore, it is not only that the sources of garden theory are heterogeneous, to say the least, but its objectives are often subversive and sometimes outright negative. In his moral essay dedicated to Lord Burlington, Pope advised English gardeners:

He gains all points who pleasingly confounds,

Surprises, varies, and conceals the bounds.

(Pope 1826: 61)

However, not only was illusion the preferred medium of the horticulturalists but the principle was applied to the art of gardening itself: it was to vanish together with the natural boundaries of the site. Thus, the Duke of Harcourt opened his essay on the informal landscape with the paradoxical epigraph: ars est celare artem, ‘art lies in the concealment of art’ (Teyssot 1991: 363).3

Others took this doctrine, despite its classical origins, as involving not so much a paradox as an actual contradiction. Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy argued that all arts, including architecture and the art of gardening, are based on Aristotelian imitation that does not mean a simple production of a formal likeness. Rather, ‘to imitate . . . is to produce a resemblance of a thing, but in some other thing which becomes the image of it. It is precisely the fictitious and incomplete within each of the arts that constitutes them as arts’ (Quatremère 1977: 120, 149). However, he observed that in the informal or English garden, the desired image of nature is simply nature itself – which is contradictory: ‘The medium of this art is reality . . . Now, nothing can pretend to be at the same time reality and imitation’ (Teyssot 1991: 369).

It seems clear enough that nothing can be at the same time reality and its image – unless it is the origin of the opposition and thus capable of occupying either side of the equation. Indeed, the garden can be seen as the chora, the unnameable container existing before categories such as truth/illusion and reality/imitation, or the separatrix between city and nature. Through the separation, it constitutes our physical environment either as ‘nature’ or as ‘culture,’ in both cases through opposition. Hence, gardens are not only constructed through the architectural act of building a wall but they themselves enact an analogous separation on a conceptual level.

In this sense, the garden is a fluid signifier without a signified, or in itself an abstract machine that can take on different roles in different contexts, constituting the perpetual other. Its matter (from Latin mater or ‘mother’, hence Mother Nature) is dependent on its haecceitas; its function is neither semiotic nor physical, neither expression nor content, but a pure function that informs both the expression-form of the discourse on architecture and the content-form of the city. Horace Walpole said that while Mahomet imagined an Elysium, William Kent created many of them (Baltrusaitis 1995: 207). In Deleuzean terms, every garden is a relocation of the Garden of Eden and a deterritorialization of nature but also its reterritorialization within the regime of signs, the necessary counterpart to architectural signifiers.

Origins

For most theorists of architecture until recent times, nature was the mother of all architecture from ornament to urban design. Vitruvius derived the Ionic capital from the leaves of a tree and attempted to return the Doric order to the simple botany of Arcadia on the Peloponnesos. Analogously, Goethe, Schlegel, Coleridge and Chateaubriand likened the Gothic cathedral to a petrified forest, a conjecture spectacularly demonstrated to the Royal Society of Edinburgh by Sir James Hall who in 1792 planted sixteen trees in his garden in the form of a Latin cross pavilion. In merely six years, the branches (which had been tied together) had grown to form a characteristic Gothic vaulting. Even larger architectural ensembles have been traced back to a vegetative paradigm. Abbé Laugier not only subscribed to the Vitruvian notion of the primitive hut but also insisted that the city be modeled after a forest (Laugier 1977: 128).4

An alternative vision permeates the roughly contemporaneous Encyclopédie which defines the city as ‘an enclosure surrounded by walls’, containing several districts, streets, public squares and other buildings, like an enclosed garden (Diderot and d'Alembert 1751–1772). The idea may ultimately come from the Bible. As Abraham Cowley wrote, ‘God the first garden made, and the first city, Cain,’ after His example (Rabreau 1991: 305). The first of all gardens, the Biblical Paradise, was a site of perfect order, rich in gold, bdellium and onyx, bursting with fruit trees and animals, intersected by four rivers, bound by a square enclosure of jasper, husbanded by an immortal man. It was created by the gods, eloh...