![]()

1

Constantinople and the Eastern Empire

The City of Constantinople

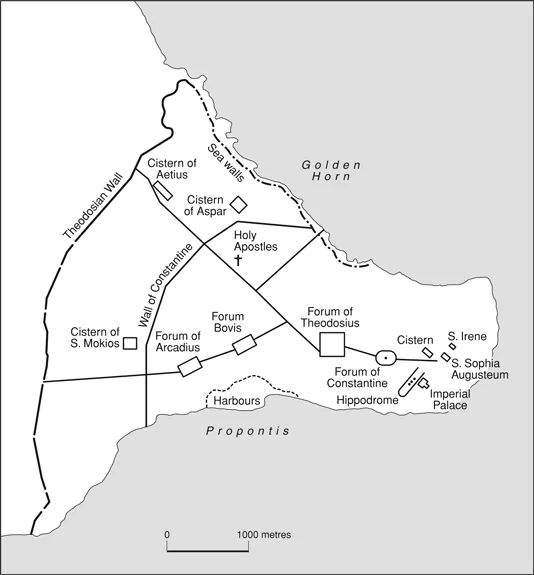

On the death of Theodosius I in AD 395, Constantinople had been an imperial seat for over sixty years, since the refoundation of the classical city of Byzantium as Constantinople (‘the city of Constantine’) by Constantine.1 Although it is common to refer to it as the eastern capital, this is not strictly correct: Constantine founded it along the lines of existing tetrarchic capitals such as Nicomedia, Serdica and Trier, and although he resided there for most of the time from its dedication in 330 to his death in 337, he seemed to envisage a return after his death to an empire partitioned geographically between several Augusti.2 It was not a novelty in itself when on the death of Theodosius I the empire was ‘divided’ between his two sons Honorius and Arcadius. What was different now was the fact that the two halves of the empire began to grow further and further apart.

Constantinople was the scene of some bitter disputes among Christians in the late fourth century, but it was still not yet a fully Christian city. Eusebius, writing of Constantine’s foundation in sweepingly panegyrical terms, would have us believe that all traces of paganism were eliminated. However, this would have been impossible to achieve in practice, short of deporting the existing population, and indeed, the later pagan historian Zosimus tells us that Constantine founded two new pagan temples.3 According to the fifth-century ecclesiastical historian Sozomen, the new city was given a senate and senate house, with classical statuary,4 and it had a Basilica and a Capitol. Presumably the latter was at first a temple like the Capitol in Rome, but teaching went on there in the fifth century as the seat of the so-called ‘University’, and by then it was surmounted by a cross.5 Constantine adorned his city with many classical statues, taken, Eusebius assures us, from pagan temples and put there as objects of derision, but more likely because they were expected as part of the adornment of a grand and monumental late antique urban centre.6 Many were crowded onto the spina in the middle of Hippodrome, others placed in the public squares.7 It was Constantine’s son Constantius II (337–61) rather than Constantine himself who was mainly responsible for the first church of St Sophia (burnt down in the Nika riot of 532 and replaced by Justinian with the present building: Chapter 5), and also for the church of the Holy Apostles adjoining Constantine’s mausoleum.8 Constantius was extremely pious himself, but the effects of the attempted restoration of paganism by his successor, Julian (361–63), were felt at Constantinople as elsewhere, and there were still pagans at court – indeed, Constantius’ panegyrist, Themistius, was a pagan. At the end of the century, John Chrysostom, who became bishop of Constantinople in 398, directed many of his sermons against the dangers of paganism. The fourth century, after the death of Constantine, was a time of ferment and competition both between Christians and between pagans and Christians, when despite imperial support for Christianity, the final outcome was still by no means certain. It was also only in the fifth century that church building began to take off on a major scale. Again, while Constantinople had been referred to as ‘New Rome’ since the time of Constantine, it was only the council summoned by Theodosius I at Constantinople in 381 that gave its bishop a primacy of honour over all other patriarchates save Rome. In an earlier gesture intended to bolster the Christian claim of the new city and claim apostolic status for it, Constantius II deposited relics of Timothy and Andrew within the empty sarcophagi of Constantine’s mausoleum.9

Constantinople had an advantage, as the seat of emperors, but it was not immune from religious and political pressures. After Theodosius I became emperor in 379 he quickly issued an edict together with Gratian condemning all heresies. This affected Constantinople, where the Christians were divided and there was a strong and vociferous Arian population. In 380 Theodosius ordered Arians to be expelled from churches, and promoted the orthodox Gregory of Nazianzus as bishop against strong opposition. He then called what became known as the Council of Constantinople (381), or Constantinople I, a council of 150 eastern bishops who met in the church of St Irene; those present confirmed Gregory and (if not very wholeheartedly) the Nicene faith. However, the election was still contested, and, unhappy at the situation, Gregory stepped down and returned to Cappadocia; he left a record of his feelings in an autobiographical poem, and while it is true that he was already a bishop, and that transfer from one see to another had been forbidden at Nicaea, Sozomen at least thought that his election would have been acceptable.10 But the affair illustrated the capacity of the patriarch of Alexandria to interfere in Constantinopolitan politics, and tensions were still high when Theodosius installed orthodox relics in a church which had previously belonged to the Arian party, following this by bringing the supposed head of John the Baptist to the city. Moreover the conversion of the Goths to ‘Arian’ rather than Nicene Christianity also added to the explosive mix in the city,11 and John Chrysostom as patriarch allowed the Goths who lived there a church, though only for orthodox worship;12 he successfully insisted on this even when under pressure from the emperor, nervous about the needs of the Gothic troops led by Gainas. The latter had successfully ousted the powerful eunuch minister Eutropius, but such was the hostility to the foreigners that a large number were massacred after taking refuge in the church, and the church was burnt down. The Goths were expelled from Constantinople in 400 and Gainas became the victim of inter-Gothic rivalries. A main, but difficult, source for Eutropius and the Goths in Constantinople is a speech by Synesius, who visited Constantinople sometime during these years as an envoy from Cyrene, and stayed for three years.13 Thus religious issues were mixed in Constantinople, with politics surrounding the reliance on eunuchs in the administration, rivalry between the western and eastern courts and the danger of relying on German soldiery. This was a crisis time for Constantinople.

Figure 1.1 The base of the obelisk in the Hippodrome, showing the emperor in the imperial box receiving gifts from barbarians

Figure 1.2 Istanbul: Justinian’s church of St Sophia

By the reign of Justinian in the sixth century, the population of Constantinople had reached its greatest extent, and may on a generous estimate have approached half a million. So large a number of inhabitants could only be supported by public intervention, and Constantine had instituted an elaborate system of food distribution based on that at Rome.14 It was from the late fourth century onwards that much of the expansion took place – something of its scale can be imagined from the fact that the original number of recipients of the grain dole was set at only 80,000. The Notitia urbis Constantinopolitanae (c. 425–30) lists 14 churches, 52 colonnaded streets, 153 private bath complexes and several cisterns. The aqueduct constructed in 373 by the Emperor Valens provided further essential water supply, and water was carried to the city from multiple sources in the Thracian hinterland; new harbours were also necessary.15 The walls built in the reign of Theodosius II in the early fifth century, and still standing in large part today, though heavily restored, enclosed a much larger area than that of the original Constantinian circuit, and though Constantinople did not equal Rome in population size, even at its height, it nevertheless provides a remarkable example of urban growth.

Pagan critics of Constantine, such as Zosimus, were highly critical of his foundation:

the size of Constantinople was increased until it was by far the greatest city, with the result that many of the succeeding emperors chose to live there, and attracted an unnecessarily large population which came from all over the world – soldiers and officials, traders and other professions. Therefore, they have surrounded it with new walls much more extensive than those of Constantine and allowed the buildings to be so close to each other that the inhabitants, whether at home or in the streets are crowded for room and it is dangerous to walk about because of the great number of men and beasts. And a lot of the sea round about has been turned into land by sinking piles and building houses on them, which by themselves are enough to fill a large city.

(New History II.35, trans. Ridley)

Of course the city failed to live up to modern standards of urban planning, but the description vividly brings out both the extent of public investment and the consequent hectic growth. The heart of the city had been planned by Constantine himself – it included the imperial palace (greatly extended by later emperors), the adjoining Hippodrome and the Augusteum, a great square leading to the church of St Sophia, a main processional street (the Mese) leading to Constantine’s oval forum with its statue of himself wearing a crown of rays like the sun god and placed on the top of a porphyry column, and Constantine’s own mausoleum, where he lay symbolically surrounded by empty sarcophagi, one for each of the twelve apostles. Despite the later proliferation of churches, this was originally less a new Christian city than a complex of public buildings expressive of imperial rule.

Whatever Constantine’s own intentions may have been, Constantinople did gradually assume the role of eastern capital. Legislation under Constantius regularized the position of the eastern senate (though it could not approach the wealth and prestige of that of Rome), and there were both eastern and western consuls; as the Notitia Dignitatum recognizes, by the end of the fourth century the same basic framework of administration existed in both east and west, and a division of the empire into two halves therefore posed no administrative difficulties.16 But in practice, during this period, the eastern government grew stronger while the western one weakened.

The East c. 400

The turn of the century nevertheless found the east facing some severe problems, chief among them the threats posed by the pressure of barbarians on the empire, and by the so-called ‘Arian question’. As we have seen, the two were linked. At the turn of the century, certain Gothic leaders and their military retinues had acquired considerable influence over the government at Constantinople, and when Synesius arrived there he found city and court deeply divided about how to deal with this potentially dangerous situation. This was not the only problem. Like his brother Honorius in the west, the eastern Emperor Arcadius was young and easily influenced by unscrupulous ministers. In this way the eastern and western governments became rivals; the western court poet Claudian, the panegyrist of the powerful Vandal general Stilicho, gives a luridly pro-western account of the situation, especially in his scabrous attacks on the eastern ministers, Rufinus, master of offices, consul and prefect of the east, and the eunuch Eutropius, head of the young emperor’s ‘Bedchamber’.17 Though he cannot rival Claudian’s level of invective, Zosimus’ account is similar in tone:

The empire now devolved upon Arcadius and Honorius, who, although apparently the rulers, were so in name only: complete control was exercised by Rufinus in the east and Stilicho in the west … all senators were distressed at the present plight.

(New Hist., V.1.9)

Even allowing for distortion, matters looked unpromising. The weakness of the imperial government is shown by the fact that in 400 Gainas had only recently been given the job of suppressing the troops led by his kinsman Tribigild who were devastating Asia Minor, only to join them himself and march on the city. The choice for the eastern government was stark: either it could follow a pro-barbarian policy and continue to attempt to conciliate such leaders, or it must attempt to root them out altogether. Both eastern and western courts were hotbeds of suspicion and intrigue, and the divisions which resulted led to the murder of Rufinus in 395 and the fall of Eutropius in 399, and were subsequently to lead to the fall and death of Stilicho in 408.

Theodosius I’s policy in relation to the Goths was to settle them on Roman land, but this did not remove the danger, and in 395 Constantinople employed the traditional policy of using subsidies to buy off Alaric, the leader of the Visigoths, who was plundering land dangerously close to the city.18 This proved disastrous; in the following year Alaric devastated the Peloponnese and large parts of the Balkans, an area whose control was disputed between east and west. A major part of the problem lay also in the fact that Gothic soldiers formed a large part of the Roman army itself. Nevertheless, the east was in a better position to buy off the raiders than the west; furthermore, significant voices, including that of Synesius, were raised in favour of expelling the Goths. When Gainas attacked Constantinople in 400, his coup was put down (albeit by another Goth, Fravitta, subsequently made consul for 401), and with it the pro-German group within government circles was defeated. This result was extremely important for the future of the eastern empire, for though the danger of barbarian pressure was to recur, the influence of barbarian generals on the eastern government was checked, and the east was able to avoid having to make the massive barbarian settlements which so fragmented the western empire. The consequences for the west were also momentous, for Alaric and his followers moved from the Balkans to Italy, besieging Rome in 408–9, demanding enormous payments in return for food and taking the city itself in 410.19 The sack of Rome was an almost unimaginable event which caused shivers to run down the spine of St Jerome in Bethlehem and sent rich Christians fleeing to the safety of North Africa and asking Augustine how God could have let this happen.

Religious Issues

The violence in Constantinople in 400 also had a religious side to it, and in the case of Rome the very fact that Alaric and his Visigoths were Christian made it doubly difficult for Christians such as St Augustine to explain why God had allowed the sack of Christian Rome to happen.20 By the middle of the fifth century the west was still the target of repeated barbarian assaults and settlements (Chapter 2) and the east was threatened by the Huns; however, the east also had other concerns. Arcadius was succeeded by his son Theodosius II (408– 50), only seven years old when his father died.21 Theodosius II’s long reign provided a stable period of consolidation during which the imperial court was characterized by an extremely pious atmosphere especially connected with the most strong-minded of his three sisters, Pulcheria, who became Augusta and regent in 414. Pulcheria chose Theodosius’ bride – the intellectual Eudocia, formerly named Athenaïs and allegedly of pagan Athenian origin, selected by means of an imperial beauty-contest – and the relationship between the two women was predictably stormy. However, Eudocia too had a strong influence on the church in the east, notably through the patronage she exercised on her visits to the Holy Land.22 To this period belong the...