- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Migration, Displacement and Identity in Post-Soviet Russia

About this book

The displacement of 25 million ethnic Russians from the newly independent states is a major social and political consequence of the collapse of the former Soviet Union. Pilkington engages with the perspectives of officialdom, of those returning to their ethnic homeland, and of the receiving populations. She examines the policy and the practice of the Russian migration regime before looking at the social and cultural adaptation for refugees and forced migrants. Her work illuminates wider contemporary debates about identity and migration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Migration, Displacement and Identity in Post-Soviet Russia by Hilary Pilkington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Policy and practice:

The formation of the

Russian migration regime

1 Did they jump or were they pushed?

Empirical and conceptual issues in post-Soviet migration

This book does not provide a history of migration studies in the former Soviet Union1 or an exhaustive account of current migrational movements in the former Soviet space.2 It focuses on a particular social phenomenon: the movement of the Russian-speaking populations3 in the former republics of the Soviet Union to the Russian Federation during and following the collapse of the USSR. It charts the experience of those displaced by this political upheaval and asks how that experience informs an understanding of the relationship between migration, displacement and identity in post-Soviet Russia. By way of introduction, this chapter outlines the empirical and theoretical obstacles which must be negotiated in order to address this question. It argues that traditional divisions between macro- and micro-level studies and existing categories of migration studies, based on a differentiation between economic (voluntary) and political (involuntary) migrants, may have to be unfixed in order to conceptualize successfully current migrational flows in the former Soviet space.

NUMBERS AND NAMES: MEASURING MIGRATIONAL FLOWS IN THE FORMER SOVIET UNION

By 1992, the world counted 17 million officially registered refugees and asylum-seekers, 4 million people in ‘refugee-like situations’, and an estimated 23 million people ‘internally displaced’ (Overbeek 1995:17). By the beginning of the 1990s, in the public mind ‘international migration’ was no longer associated—as it had been in the 1960s and 1970s—with primary and, subsequently, secondary labour migration but had become synonymous with the term ‘refugee crisis’ (Salt 1989:432). In a world already deeply troubled by mass population movements, the collapse of the Soviet Union was, without doubt, unwelcome; it created a host of new international borders and potential refugees to cross them. Moreover, the collapse of the Soviet Union did not solve ethnic conflict in the region or the flight across borders which it had provoked. The process of decolonization and nation-state building in the newly independent states only encouraged further population displacement in the region. Consequently, in the last decade the former Soviet Union has been transformed from a country whose population was surprisingly reluctant to migrate, especially over long distances, into a region whose very stability is threatened, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), by current migration trends.4

In these migrational flows, it is Russia which has proved the net recipient; since 1993 Russia has had a positive migrational exchange with all of the former Soviet republics. Table 1.1 indicates net migration rates between Russia and the former Soviet republics in 1994.5 Using official data broken down by nationality on the numbers entering and leaving Russia from each of the former Soviet republics, this table illustrates three important trends. First, the positive total balances (‘all nationalities’) show that Russia today is a recipient, not a donor nation, in terms of migration within the post-Soviet space. Second, the data show that, with the exception of the war-torn Transcaucasian states, it is ethnic Russians6 who make up the majority of the net in-migration, ranging from 85 per cent from Belarus to 62 per cent from Tajikistan. Finally, the data show that many non-Russians choose to migrate to Russia, including, in the case of the Transcaucasian states and Ukraine, large numbers of the former republics’ titular nationalities;7 82 per cent of net in-migration from Armenia consisted of ethnic Armenians, for example.

Table 1.1 Net migration between the Russian Federation and the former Soviet republics, 1994

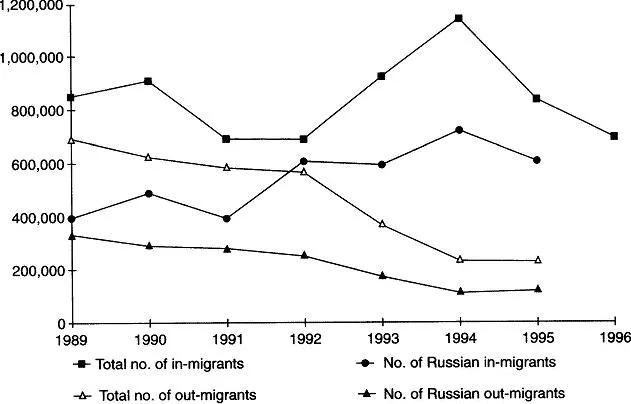

Given the concern in government circles about the prospects for future natural population growth in Russia—due to rising mortality but falling birth rates—one might expect a favourable response to what are quantitatively moderate rises in in-migration. Indeed, as Figure 1.1 shows, total in-migration from republics of the former Soviet Union has fallen for two years in succession and the figure for 1996–700,000—is actually less than the in-migration to Russia in 1980 (876,000) (Goskomstat 1995:400). However, it is not the annual in-migration figures which concern the Russian authorities so much as the manner in which these people arrive—since they have significant social welfare needs—and, above all, the ethnic character of the migration which indicates a potential for mass inward flows in the future. There were 25.3 million ethnic Russians living in Soviet republics other than the Russian Federation according to the last Soviet census of 1989. In addition there were approximately 11 million members of other ethnic groups living outside their titular republic whose primary cultural affinity is to Russia and who are often subsumed into the ‘Russian’ diaspora as ‘russophones’ or the ‘Russian-speaking’ population and considered potential returnees to Russia.

Figure 1.1 In-migration to and out-migration from the Russian Federation from and to the former Soviet republics, 1989–96

Source: Goskomstat 1995:422–3

Source: Goskomstat 1995:422–3

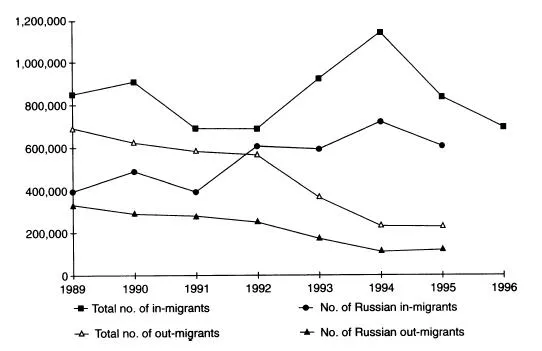

Since July 1992, the Federal Migration Service of the Russian Federation has been monitoring migrational flows from the former republics and registering those arrivees who were forced to leave their former place of residence as a result of persecution. Of the 3 million people having moved from the former republics to Russia since then, just over a million have been registered as forced migrants or refugees.8 Figure 1.2 shows the number of forced migrants and refugees registered annually since data collection began. These figures represent registered forced migrants and refugees only and, although the procedures for gathering data have been significantly improved since 1992, none the less there are considerable problems in using these data as a reliable indicator of total numbers of ‘involuntary’ migrants from the former republics.9 The most recent problem is that of the peculiar status being given to those displaced as a result of military conflict in Chechnia. Although currrent Russian legislation does provide for the granting of ‘forced migrant’ status to those displaced within the Russian Federation (see Chapter 2), the authorities have been increasingly reluctant to register those fleeing Chechnia as refugees or forced migrants. The Russian Federal Migration Service registered a total of 117,000 refugees or forced migrants from Chechnia in the period 1992–5 (Codagnone forthcoming). Thus it is estimated that less than 9 per cent of those who fled Chechnia after December 1994 obtained such status and that there are currently almost 500,000 displaced people from this region who have not been registered and granted appropriate status in the normal way (Mukomel 1996:143).

Figure 1.2 Number of refugees and forced migrants registered by the Federal Migration Service, 1992–5

Source: Federal Migration Service data cited in Codagnone (forthcoming)

Source: Federal Migration Service data cited in Codagnone (forthcoming)

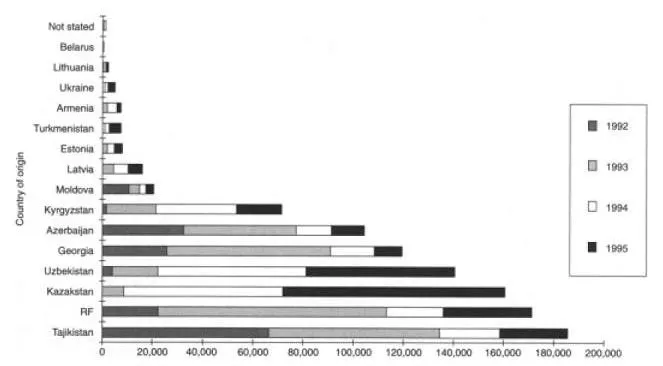

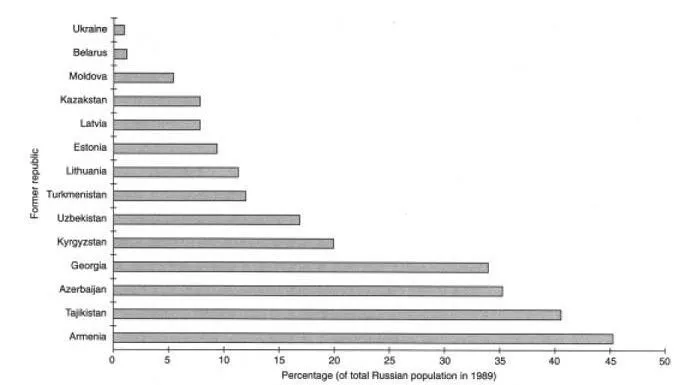

From these data, the Federal Migration Service seeks above all to determine the size and direction of future migrational flows. Figure 1.3 shows the change in the region of origin of refugees and forced migrants over time. It clearly indicates the replacement of the Transcaucasian10 states by Central Asia11 and Kazakstan as chief sources of out-migration from 1994. Of course, these data require contextualization. The fact that half a million Russians have left Kazakstan since 1990, for example, does not necessarily indicate a mass exodus; it actually constitutes only 8 per cent of the Russian population in Kazakstan (which numbered over 6 million in 1989) (Codagnone forthcoming). On the other hand, the very size of the Russian population suggests that there is potential for even greater numbers to return to Russia in the future. Russian government estimates are that a further 2 million to 5 million forced migrants will move to Russia from the former republics over the next ten years (Dmitriev 1995b; Lemon 1995a).12 Figure 1.4 shows the percentage of the Russian populations in the former republics having out-migrated in the period 1990–4 and indicates that it is in only a few former republics—specifically Tajikistan and the three Transcaucasian republics—that the movement of the mobile Russian population is almost exhausted. Indeed, the Federal Migration Service has already recorded a rise in the number of forced migrants and refugees registered in 1995 over 1994 (‘Migratsionnii prirost uvelichilsia pochti v dva raza’ 1995; Dmitriev 1995b), even without including those displaced following the military intervention in Chechnia. The source of this increase is equally clear: 73 per cent of refugees and forced migrants registered in 1995 arrived from Central Asia and Kazakstan.13

Predictions regarding the region of origin of future returnees suggest the largest inflow will continue to come from the states of Central Asia and Kazakstan. The head of the Federal Migration Service, Tat’iana Regent, has estimated that Russia will receive 3 million returnees from that region alone (Slater 1994:41) while academic analyses suggest that 30–50 per cent of the Russian-speaking population from the region will migrate (Levanov 1993:26).14 However, estimates of the number of Russians likely to leave other areas are being revised down. Regent’s prediction in 1993 that 500,000 would return from the Baltic states15 now appears high. The Russian Ministry of Labour currently expects no more than 300,000; a figure in agreement with Levanov’s estimate of 18–20 per cent of the Russian-speaking population in the Baltic states (Levanov 1993:36). The migration of Russians from those former republics which are culturally close to Russia—Belarus and Ukraine—appears more likely to take the form of labour migration than permanent out-migration in the majority of cases. This is supported by the data in Table 1.1 and Figures 1.3 and 1.4;

Figure 1.3 Number of refugees and forced migrants registered in 1992–5, by region of origin

Source: Federal Migration Service data cited in Codagnone (forthcoming)

Source: Federal Migration Service data cited in Codagnone (forthcoming)

Figure 1.4 Percentage of Russian populations in the former republics having out-migrated, 1990–4

Source: Codagnone (forthcoming)

Source: Codagnone (forthcoming)

Federal Migration Service data confirm the indication in Goskomstat (State Statistics Committee) statistics that the majority of those entering Russia are ethnic Russians. Russians have consistently constituted the majority of inward migrants from the former republics as a whole (54 per cent in 1990, 66 per cent in 1992 and 63 per cent in 1994 (Goskomstat 1995:422)) as well as of officially registered refugees and forced migrants (76 per cent in 1993, 67 per cent in 1994 and 77 per cent in 1995 (Komitet po delam SNG i sviaziam s sootechestvennikami 1996; Informatsionno-analiticheskii Biulleten’ 1995:21)). The balance is constituted primarily by members of the titular nationalities arriving from their own countries afflicted by civil war, economic crisis and political instability. Table 1.1 indicates that Armenians, Azerbaijanis and Georgians are most likely to move from their own states to Russia. In contrast Belarusians and Kyrgyz are more likely to leave Russia for their own countries.

As is discussed in detail in Chapter 2, these data are so coloured by the politics of the migration debate that it is difficult to construct any ‘true’ picture; they can be read either as showing a sharp increase in the proportion of non-Russian immigrants in 1994 (Russian Independent Institute for Social and Nationality-based Problems 1994) or as indicating an overall increase in the proportion of Russians over the period 1990–4 (Trubin 1996). What is probably indisputable is that the figures suggest that a significant number of those migrating to Russia at the current time are labour migrants. Indeed, during the first half of 1996, 222,000 foreign citizens from 116 countries were officially employed in Russia, which is 30 per cent more than during the corresponding period of 1995. Of these over half had come from countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States and labour migration almost certainly accounts for the surprisingly high in-migration noted in Table 1.1 from Ukraine; over a third of the total number of registered foreign workers are currently citizens of Ukraine (‘Labour immigrants in Russia’ 1996).

A new flow of citizens of countries from beyond the former Soviet Union (the ‘far abroad’) into Russia is causing the Russian government increasingly to distinguish between these people (often referred to as ‘asylum-seekers’) and refugees from the former republics (the ‘near abroad’).16 According to UNHCR data, by 1 July 1996 almost 19,000 families (70,000 people in total) from the ‘far abroad’ had submitted applications for asylum. Most were fleeing Afghanistan (63 per cent), Iraq (mainly Kurds) (10 per cent) and Somalia (9 per cent) (Vynuzhdennie Pereselentsy v Rossii 1995:54; Michugina and Rakhmaninova 1996:48). The Moscow office of the International Organization for Migration estimates the current number of such asylum-seekers at 120,000. As in other countries of Europe, in government thinking the issue of asylum-seekers is inextricably bound to that of illegal or undocumented migrants. In Russia this concern is new but very real; there are claims that hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants have entered Russia due to poor security along the external borders of Russia and other CIS states (Rutland 1995). The head of the Federal Migration Service stated that there were 500,000 ‘illegals’ in Russia at the end of 1995 and suggested that this number would grow by 100,000 annually. More extreme estimates are that illegal immigration may be running at more than 500,000 people a year (Russian Independent Institute for Social and Nationality-based Problems 1994). Some of these are economic migrants (mainly Chinese and Vietnamese), others are so-called ‘transits’: asylum-seekers and undocumented migrants—mainly from Ethiopia, Somalia, Sri Lanka and Iraq—using Russia as a staging post to Scandinavia, Western Europe and North America.

A final migrational flow causing concern is the outflow from the former Soviet Union of its most active and educated population to the west. Fears were raised by the rapid growth in emigration following the enactment of legislation allowing free exit from the Soviet Union; whereas up to the mid-1980s an average of around 3,000 people emigrated abroad from Russia annually, by 1990 the annual total had reached 104,000 (Michugina and Rakhmaninova 1996:47). Initial alarm about emigration to the west has largely abated, however, as predictions of its acceleration—ranging from 2.5 million to 25 million (Segbers 1991:6)—have not been realized. These estimates were constructed from public-opinion data and sociological surveys which clearly captured aspiration rather than real intention and are cited now primarily for political effect (see Salt 1992:66; Chesnais 1992:37; Grecic 1993:145).

Although the issue of out-migration from Russia to the west lies beyond the scope of this book, there are points of intersection with migrational flows from the former republics to the Russian Federation, with which this book is concerned. First, emigration from Russia to the ‘far abroad’ has stabilized in the 1990s; just 110,000 people emigrated from the Russian Federation in 1995 compared to the 104,000 in 1990 noted above. Second, emigration out of Russia to the west has been low in comparison to emigration from other former Soviet republics. Emigration from Russia has constituted around 30 per cent of total migration out of the former Soviet Union when the population of Russia constituted 51 per cent of the Soviet population (Michugina and Rakhmaninova 1996:47). Likewise, ethnic Russians have constituted only 26 per cent of those emigrating (ibid.). This is explained by the fact that the initial wave of east-west emigrants largely consisted of members of smaller ethnic groups who had ‘ethnic homelands’ or established diasporas in the west, primarily Armenians, Jews, Germans, Poles and Greeks (Terekhov 1994; Shevtsova 1992). Indeed, 52 per cent of those having emigrated abroad from Russia are ethnic Germans (Michugina and Rakhmaninova 1996:47). Thus Michugina and Rakhmaninova suggest that as few as 140,000 Russians have emigrated between 1989 and 1995 and these primarily due to mixed marriages with other ethnic groups more prone to emigration. Fears in the west of mass economic migration from Russia to Wester...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- TABLES

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION

- PART I: POLICY AND PRACTICE: THE FORMATION OF THE RUSSIAN MIGRATION REGIME

- PART II: GOING HOME? SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ADAPTATION OF REFUGEES AND FORCED MIGRANTS

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY