In late 1991, with the sudden collapse of the Soviet Union, the five Central Asian republics of the USSR became independent countries. Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan had no experience of nationhood before they were incorporated into the Russian empire during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The completely unexpected challenges of nation building were superimposed on the transition from a centrally planned to a market-based economy, which had begun in the late 1980s but had little influence on Central Asia before the Soviet economic system began to unravel in 1991. The indigenous capacity for economic management was limited, because during the Soviet era development strategies were determined in Moscow. The region had been planned as a single unit, or perhaps more accurately as part of the single unit that had been the Soviet economy, and all five countries suffered serious disruption from the replacement of the USSR with fifteen independent countries. Attempts to maintain economic links by retaining the ruble as a common currency in 1992–93 exacerbated the problem of hyperinflation and had been abandoned by the end of 1993. Under these multiple adverse conditions, even the ability of the countries to survive was uncertain.1

By the early twenty-first century all five countries had essentially completed the transition from central planning. Within the common bounds of resource-based economies and autocratic regimes, the five countries gradually became more differentiated as their governments introduced national strategies for transition to a market-based economy. The aim of this book is to describe the different economic polices and to analyze the outcomes.

The inherited political structures were identical and in four of the countries First Secretaries appointed by Mikhail Gorbachev remained in power as presidents, but the national leaders adopted surprisingly diverse economic strategies. The Kyrgyz Republic embraced the advice from Western institutions and advocates of rapid change and, within limits, its president fostered the emergence of the most liberal regime in the region. Turkmenistan is the polar opposite, where the president has established a personality cult and has minimized economic change. Kazakhstan in the early 1990s appeared to be accompanying the Kyrgyz Republic on a liberal path, but the president became more autocratic as the decade progressed and the economy became dominated by a small group of people who controlled the media and the banks. Uzbekistan retained a tightly controlled political system, but without the personality cult of Turkmenistan, and its economic reforms have been gradual and modest. Tajikistan has been in a different category, because it was the only one of the five countries not to evolve peacefully from Soviet republic to independent state under unchanged leadership. The bloody civil war of 1992–93, which reignited in 1996–97, dominated political developments and delayed implementation of a serious and consistent economic strategy.

The five countries’ economic performance has differed, to some extent reflecting policy choices, but since 2000 the comparative situation has been dominated by the global boom in oil prices. During the 1990s Kazakhstan’s output performance was inferior to Uzbekistan’s, but since the turn of the century Kazakhstan, as a significant oil and gas producer which has also had major new discoveries coming on line, has experienced an economic boom. Turkmenistan, despite its abundant natural-gas reserves, has suffered from dependence on Soviet-era pipelines, but since 1999 the energy boom appears to have alleviated pressures to change the country’s poor economic policies. Both gradual-reforming Uzbekistan and rapid-reforming Kyrgyz Republic have enjoyed less spectacular growth, and have clearly lower living standards than Kazakhstan. Tajikistan is even worse placed; the economy has recovered from a very deep trough, but slowly, and Tajikistan now ranks among the world’s poorest nations.

The remainder of this chapter provides further background on the initial conditions and choice of development strategies, and provides preliminary assessments of comparative economic performance and a snapshot of social and economic conditions a decade after independence. Chapters 2–6 examine each national economy in greater detail, and Chapter 7 reviews the relative economic performance of the five countries. Patterns of which households gained and which lost from the transition to a market economy are analyzed in Chapter 8. A key issue in explaining international differences in performance is the individual countries’ natural-resource endowment, the consequences of which are analyzed in Chapter 9. The importance of natural-resource exports served as a catalyst for integration into a wider economic circle, and Chapter 10 analyzes alternative strategies, multilateral and regional, pursued by the Central Asian countries. Chapter 11 draws some conclusions.

1.1 Initial Conditions and Choice of Economic Policies

Comparing the economic development strategies and the performance of the new independent countries of Central Asia is intellectually exciting because they started from fairly similar initial conditions. Before independence they were all republics of the Soviet Union, and had the same economic system. Although during the Gorbachev era some local economic experiments had taken place in the Baltic republics, parts of the Russian republic, and elsewhere in the USSR, such experiments had been absent from Central Asia, which was generally viewed as the most conservative area in the USSR.

Together with Azerbaijan, the other majority Islamic republic, the Central Asian republics were the poorest Soviet republics. Although inequality, as measured by Gini coefficients, did not differ much from the Soviet norm, they had the largest proportion of households living below the poverty line (Table 1.1). Human-capital measures, such as life expectancy or the almost universal literacy, were, however, high for the income level.

Per capita output in 1990 has been estimated at between $1,130 and $1,690 for the four southernmost republics and $2,600 for the Kazakh republic. Although the relative values in Table 1.1 are a reasonable guide to the ranking of Soviet republics by living standards, the absolute dollar values must be treated with caution due to the insoluble problems of the Soviet Union’s artificial relative prices. The World Bank estimates in Table 1.1 place the Kazakh republic’s 1990 per capita GNP of $2,600 on a par with that of Hungary ($2,590) and somewhat lower than Iran’s ($3,200), while the other four republics had per capita GNP comparable to that of Turkey ($1,370) or Thailand ($1,220); post-1991 experience suggests that the Central Asian republics were behind these comparators.2

The Central Asian republics’ economic role in the USSR had been as suppliers of primary products—mainly cotton, oil, and natural gas—and minerals, although the specific resource endowment varied from country to country. The Kazakh republic’s higher living standards reflect a more diversified economy with grain exports and a variety of mineral and energy resources. Central Asia was the most heavily rural part of the USSR, and Kazakhstan was the only one of the five Central Asian republics with over half of its population living in urban areas (see Wegren 1998, p. 164).3 The Uzbek republic’s economy was dominated by cotton, as were neighboring parts of the other republics. Turkmenistan had experienced a boom in natural-gas production during the final decade of the USSR, while the mainly mountainous Kyrgyz and Tajik republics had fewer exploitable resources.

The terms of trade calculations in Table 1.1 reflect the underpricing of energy and overpricing of manufactured goods in the Soviet economy. Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan as major exporters of oil and natural gas would benefit substantially from replacing the artificial Soviet prices by world prices, while the other Central Asian successor states would gain sufficiently from improved prices for cotton and minerals and lower prices for manufactured goods to more or less offset the higher prices of energy imports. In practice, Uzbekistan benefited from the shift to world prices because it was able to reduce its dependence on imported fuel and because world cotton prices boomed during the first half of the 1990s, while Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan were unable to immediately benefit because the dominant exit route for their oil and gas exports was via the monopsonist Russian pipeline network.

Table 1.1. Initial conditions: republics of the USSR 1989–90.

Sources: columns 1–2, World Bank (1992, pp. 3–4); columns 3–4, Atkinson and Micklewright (1992, Table U13), based on Goskomstat household-survey data; column 5, Tarr (1994); column 6, World Bank, World Development Report 1993, pp. 249–50; column 7, UNDP, Human Development Report 1992.

Notes: (a) GNP per capita in U.S. dollars computed by the World Bank’s synthetic Atlas method; (b) poverty is defined as the number of individuals in households with gross per capita monthly income less than 75 rubles; (c) impact on terms of trade of moving to world prices, calculated at 105-sector level of aggregation using 1990 weights.

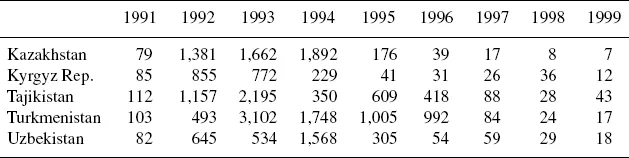

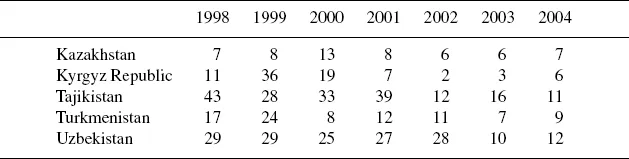

Table 1.2. Inflation (change in consumer price index) 1991–2004 (percent).

Source: EBRD Transition Report Update, April 2001, p. 16.

Source: EBRD Transition Report Update, April 2004, p. 17.

Notes: 2003 figures are preliminary actual figures from official government sources. Data for 2004 represent EBRD projections.

The Central Asian republics were almost totally unprepared for the rapid dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.4 As new independent states at the end of that year, they faced three major economic shocks: transition from central planning, dissolution of the Soviet Union, and hyperinflation. Dismantling the centrally planned economy created severe disorganization problems, which led to output decline everywhere in Central and Eastern Europe (Blanchard 1997). The dissolution of the Soviet Union added to these problems as supply links and demand sources were disrupted by new national borders and attempts to retain resources within these borders. In Central Asia the absence of any tradition of nationhood and the need to create new national institutions compounded these difficulties. Attempts to maintain existing commercial and political links by retaining a common currency fueled hyperinflation (Pomfret 1996, pp. 118–29).

Prices increased very rapidly in 1992, by more than 50% per month in all five countries (Table 1.2). The currency became the dominant economic issue in 1993, and four of the countries introduced national currencies—the Kyrgyz Republic in May, and Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan in November. A national currency was a prerequisite for gaining control over inflation and hence establishing a functioning market economy in which relative price changes could be observed and could perform their allocative function. Tajikistan was torn by civil war and did not introduce a national currency until May 1995.5

A national currency may have been a necessary condition for macroeconomic stability and effective economic reform but it was not a sufficient condition, and each of the countries moved along a different reform path.

The Kyrgyz Republic is usually viewed as one of the most dynamic reformers among the former Soviet republics. It has been strongly supported by international institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, and in July 1998 became the first former Soviet republic to accede to the WTO. The Kyrgyz Republic was the first Central Asian country to succeed in curbing hyperinflation, bringing the annual inflation rate below 50% in 1995. Creating the institutions needed to support a functioning market economy was, however, more arduous, and important markets like the foreign exchange, domestic capital, and national labor markets are still not effective in allocating resources. Manufacturing output fell substantially during the 1990s, and the increased proportion of GDP that was made up by agriculture primarily reflected urban–rural migration as unemployed urban workers returned to their family’s village. The only major growth pole has been the Kumtor gold mine. These structural problems may reflect the initial backwardness of the economy, not just in income levels but also in human capital, which has been exacerbated by substantial emigration.6 The impetus for reform in the Kyrgyz Republic slowed after 1998 when the economy was hit by contagion from the Russian Crisis and by a domestic banking crisis, but reforms have been resumed in the twenty-first century.

Kazakhstan had a better base for creating a market economy, given its higher living standards and h...