![]()

1

Marrying into the Military

Colonization, Emancipation, and Martial Community in West Africa, 1880–1900

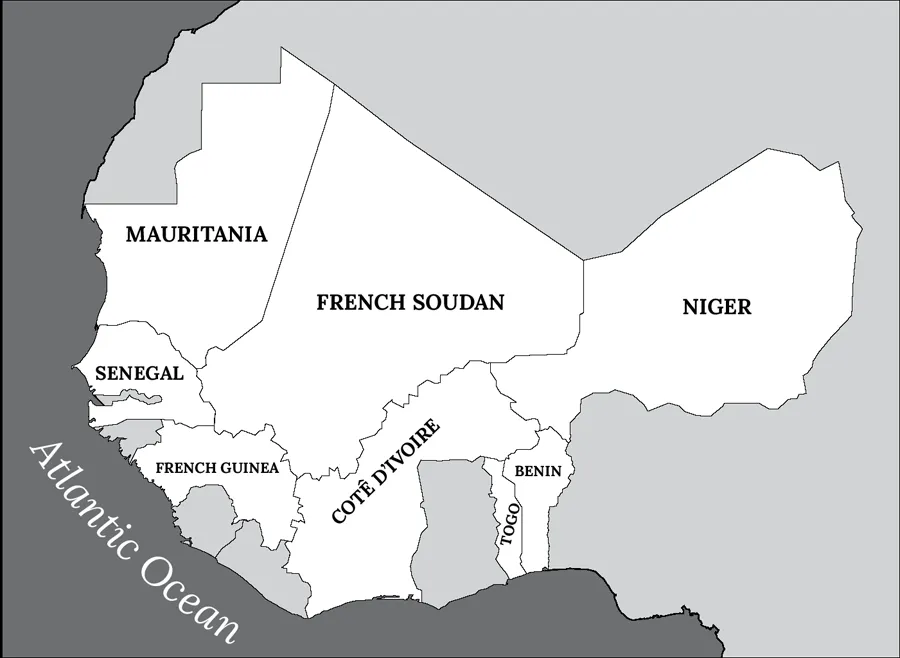

TIRAILLEURS SÉNÉGALAIS’ CONJUGAL TRADITIONS COHERED AT A TIME in which France intensified and expanded its military presence in West Africa. During the final decades of the nineteenth century, locally recruited troops across the African continent played important roles in the escalation of everyday violence, social destabilization, and the operation of colonialism. Their presence in the ranks of the European-commanded armies influenced local expressions of militarization and colonial rule. In West Africa, soldiers participated in France’s violent conquest of regions extending from the Senegal River basin to the shoreline of Lake Chad and along the coasts of what would become Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, and Dahomey. French colonization coincided with, and exacerbated, regional conflicts led by politicized Muslim leaders in the West African savannah and Sahel. Tirailleurs sénégalais fought in pitched battles with the adherents of Mamadou Lamine Drame in Bundu, Samory Touré across his Wassulu Empire, and Ahmadu Seku Tall in Segu—the capital of the Tukulor Empire. The French military eliminated opposition to colonial rule with superior military technology and tirailleurs sénégalais. Via tirailleurs sénégalais, France incorporated West African territories into the nascent colonial state. Subsequently, these soldiers assisted in initiating processes and introducing institutions meant to foster postconflict stability. Empowered by the colonial state, African soldiers influenced changes in important sociocultural traditions, including slavery and marriage. They simultaneously engaged in conjugal practices that would serve as the foundation for tirailleurs sénégalais’ marital traditions.

The earliest manifestations of the French colonial state and military depended on West African women and the households they created with tirailleurs sénégalais.1 The importance of women in these institutions has not been adequately addressed in the historical literature on colonial armies in Africa. Early publications focused on military technology, battles, and political power, as well as relying on the troublesome dichotomies of colonizer versus colonized and/or narratives of collaboration versus resistance.2 Unintentionally, these works produced political histories of conquest that disregarded the subtle (and not so subtle) effects of militarization across African sociocultural landscapes. In the past decade, Africanist military historians have begun to locate women’s experiences in Europe’s conquest of the continent, as well as to map gendered results of colonial and postcolonial militarism.3 This chapter examines how women and gender were consequential to the early iterations of the French colonial military and state. Women participated in military campaigns stretching from Atlantic coastlines into southern Saharan towns. West African communities experienced the tragedies of war and profound transformations in gerontocratic and gendered authority. Colonial militarization altered local institutions that gave social order to West African societies—armies, slavery, and marriage. With conquest, the colonial military and its African soldiers brought heteronormative marriage and slave emancipation under their jurisdiction, which had wide-ranging effects on conjugal behavior and marital legitimacy within the tirailleurs sénégalais. Military records concerning tirailleurs sénégalais’ households during colonial conquest allow historians to track changes and continuities in West African marital traditions before civilian administrators set up indigenous court systems in the early twentieth century. West African women, soldiers, and the French colonial military contested marital customs within military spaces, where masculinity and paternalism weighed on decisions concerning legitimate marriage and divorce. Tirailleurs sénégalais’ emergent conjugal traditions would later inform civilian administrators about West African marital rites.4

Warfare, slave emancipation, and marriage were processes that influenced how African women became tirailleurs sénégalais’ conjugal partners and/or auxiliary members of the French colonial army. Conjugal traditions cohered in military contexts, but were informed by precolonial West African and French marital and martial customs. In order to track their origins and transformations, this chapter pays careful attention to the relationship between slavery, emancipation, and military service. Precolonial states and the French colonial state relied heavily on enslaved and/or formerly enslaved men to fill the ranks of their armed forces. Relatedly, the dynamic relationship among female slavery, emancipation, and marriage informs our understanding of how West African women, across the colonial divide, came to be affiliated with military men. The trial of Ciraïa Aminata, detailed below, illustrates how colonial agents obscured the distinction between female slave and wife in colonial African military households. Militarization increased women’s vulnerability and reduced their social ties and status within their natal communities. When colonial soldiers were involved, nineteenth-century West African communities lost their authority over the marital rites and traditions that provided legitimacy to conjugal relationships in West Africa.

MAP 1.1. French West Africa. Map by Isaac Barry

French conquest introduced new mechanisms and institutions that provided displaced West African women and men with gendered pathways toward emancipation and marriage. Military officers created Liberty Villages, which tripled as safe havens, spaces of emancipation, and sites of labor recruitment for the colonial state. Men became soldiers and women became their wives. Similar to Mamadou Lamine Drame’s conjugal partners (described in the introduction), West African women experienced “emancipation” from slavery and “marriage” to tirailleurs sénégalais as analogous or coterminous processes. Military marriages, when paired with emancipation, served to liberate men into the public sphere and women into the private sphere or household.5 Efforts to eradicate slavery through military conquest gendered the emancipation process—masculinizing the colonial state and its employees.6 The French military’s support of these gendered processes made West African women crucial to recruitment efforts and labor stabilization within the tirailleurs sénégalais. Female West Africans—slave or not—transformed into colonial subjects and mesdames tirailleurs.7

The French colonial military expected mesdames tirailleurs to provide their husbands with domestic labor, as well as to provide other troops with essential services like food preparation and laundering services. Active soldiers campaigned with their families and/or established new households near war fronts while serving state interests. African military households conformed their traditions of familial reciprocity and patron-client relationships to the hierarchical structure of the colonial military.8 Tirailleurs sénégalais households depended on each other and the colonial state. They reproduced precolonial sociocultural hierarchies and relationships of exchange while adapting to the colonial military’s systems of redistribution and its allocation of resources to their military families. West African conjugal traditions evolved within French conquest. African military households on the frontiers of the colonial state result from dramatic transformations in gendered power in nineteenth-century West Africa.

SLAVES AND SOLDIERS: INDIGENOUS AND COLONIAL MILITARY TRADITIONS

During the 1880s and 1890s, the French military benefited from recruitment practices that constrained African men’s liberty and put them to work for the nascent colonial state. Slavery and coerced labor were key features of the French colonial military and African military households in the late nineteenth century. Governor Louis Faidherbe created the tirailleurs sénégalais in 1857 in response to several contingent nineteenth-century processes—a renewed and growing presence of French concessionary companies along West African coastlines and waterways, colonial state expansion, and the protracted abolition of slavery. French colonization in late nineteenth-century West Africa occurred through military conquest. The French military recruited West African men for extensive inland campaigns. Many tirailleurs sénégalais were former slaves who had secured their freedom by enlisting in the colonial military. At the front lines of French colonization, these slaves-turned-soldiers assisted in liberating and protecting other recently emancipated slaves. The French colonial military’s dependence on slaves and former slaves paralleled indigenous West African military practices. Nineteenth-century French colonial labor schemes—laptots, engagé à temps, rachat—employed enslaved laborers, who were also channeled into the tirailleurs sénégalais.9 Additionally, Liberty Villages served as entry points into military service. French colonial officials and village chiefs compelled able-bodied men in these sites of refuge to enlist in the tirailleurs sénégalais.

The military conquest of inland West Africa followed France’s universal declaration of slave abolition in 1848 and the Third Republic’s (1871–1940) commitment to eradicating forms of slavery in empire. In the 1880s, the emancipation of domestic slaves was a formal objective of colonization, which would deeply entangle military officials in processes of emancipation, recruitment, and conjugal affiliation. Forms of domestic slavery were pervasive to the processes that produced African soldiers and military households.10 Domestic slavery describes a continuum of forms of human bondage that were subtler, if no less brutal, than the chattel slavery affiliated with the plantation colonies of the Americas. Scholars have described domestic slavery as a transitional process, where outsiders were incorporated into new kinship groups/communities through an initial phase of enslavement.11 French civilian and military administrators believed in this assimilationist model and argued it was standard to African and Muslim forms of slavery in West Africa.12 Through transgenerational social integration, enslaved people would become full community members and gradually efface their slave origins or foreign status. Domestic slavery enabled powerful lineages to accumulate dependents and secure labor. Nineteenth-century French observers viewed domestic slavery as essential to the social fabric of West African societies.13 They were hesitant to enforce wholesale emancipation in their West African territories because they feared it would create social upheaval and inhibit their ability to manage recently acquired territories. Instead, early colonial officials fostered institutions that moderated the enforcement of emancipation and accommodated local practices dependent upon slavery. The military used emancipatory mechanisms that assimilated marginalized West Africans into the nascent colonial state and provided them with limited opportunities to achieve social mobility. Membership in the tirailleurs sénégalais provided former slaves with circumstances in which they could accumulate resources and acquire conjugal partners and dependents. The gradual amelioration of their low social status during their military careers extended to their offspring. In this way, the tirailleurs sénégalais’ measured integration into the colonial state was analogous to the ways in which the French believed non-casted domestic slavery functioned in West Africa.

The colonial state’s incorporation of enslaved men and men with slave ancestry into the tirailleurs sénégalais resembled aspects of precolonial West African military recruitment practices.14 Many West African societies valorized martial skills. Men (and in some cases women) in those societies were trained in military skills at various stages of maturation.15 The Bamana kingdoms of Ségou and Kaarta exemplified warrior-based states in nineteenth-century West Africa.16 Some societies designated specific lineages or castes to specialize in martial skills. Martial lineages or castes were affiliated with slave status, like the ceddo of the Wolof kingdoms. Although affiliated with slave status, soldier castes often held privileged positions among the slave classes.17 Expansionist states absorbed prisoners of war and refugees into their military forces. Many of Samory’s sofas, or soldiers, were captives prior to their conscription into his army.18 Sofas acquired, employed, and incorporated slaves into the expansionist Samorian state as groomsmen, attendants, and orderlies. Enslaved women, who provided domestic and auxiliary military services, were among sofas’ wives and dependents.19 Many new recruits in the tirailleurs sénégalais were refugees or former sofas looking for new patrons. They lacked the ability to return home and reclaim their homes or farms. Enlisting in the tirailleurs sénégalais provided these men with the opportunity to earn wages, as well as to secure access to other types of resources provided by the colonial military state. Sofas-turned-tirailleurs sénégalais also continued Samorian practices of acquiring wives on campaign.20 The colonial military allocated rations to soldiers and allowed them to set up family homesteads adjacent to military posts. In some cases, the colonial military assisted tirailleurs sénégalais in locating and liberating their dispersed kin.21

The French colonial military’s methods of recruitment and retention of soldiers expanded upon earlier nineteenth-century colonial labor schemes. Laptots provide a historical through line, which connects Atlantic African forms of slavery with French colonial labor systems that include the tirailleurs sénégalais. Laptots were men employed on limited-term contracts to crew and provide security on French merchant and military ships between trading posts in the Senegambia. Laptots first appeared in the colonial record during the early eighteenth century, when they worked for French royal charter companies participating in the transatlantic slave trade. In the nineteenth century, laptots hailed from a variety of ethnolinguistic groups and included free men, slaves, and former slaves. Emancipation could occur before, during, or after laptots’ period of employment. In some cases, representatives of the French state freed the slaves that became laptots. In other examples, slave owners hired out their slaves to work in laptots corps. In this type of arrangement, masters received enslaved laptots’ enlistment bonus and part of their wages. This practice existed contemporaneously with engagé à te...