![]()

PART I

Contexts

![]()

1

Power and International Trade in the Savanna

THIS CHAPTER offers a preliminary overview of the main drivers of the history of the central African interior. Its principal aim is to contextualize the case studies presented in parts two and three of this book by exploring, first, the workings of power in the central savanna from c. 1700 and, second, the changes in governmentality precipitated by its growing involvement in global trading networks over the course of the nineteenth century. As Steven Feierman and other historians of eastern Africa have argued, such changes were often revolutionary, leading to the emergence of new social groups, new polities, and new ways of enforcing authority.1 In the troubled nineteenth century, individual charisma and military success became undoubtedly more central to the wielding of political power than they had been in previous centuries. Still, the impact of violent innovation was not the same everywhere. The “hereditary” and “mystical” principles of political organization discussed in the first section of this chapter did not disappear overnight, and an exclusive stress on historical ruptures runs the risk of obfuscating patterns of continuity.2 The experiences of dislocation and turmoil were pervasive, but so were attempts to neutralize or adapt to them. Commercially driven violence and the increasing availability of firearms could provide the bases for the growth of new warlord polities and related mercenary groups, and they could bring to a premature end preexisting state-building efforts. But they could also be harnessed by, and thus inject new life into, the latter. Broad generalizations, then, are not the best way to address the changing political culture of the central savanna in the nineteenth century. Neither should the one-sidedly gruesome descriptions that many coeval Western observers indulged in be swallowed hook, line, and sinker. What can be said with certainty is that the intrusion of merchant capital and its African spearheads left central Africa more politically and culturally heterogeneous than it had ever been at any time in its long past.

The chapter also introduces the theme of firearms, describing the timing and modalities of their arrival on the central savanna and offering some initial indications of the disparate reactions that they gave rise to. The interaction between the peoples of the central African interior and firearms must be regarded as an instance of cross-cultural technological consumption. African understandings of guns were as complex as they were contingent, and one of the overarching arguments of this book is that the meanings and functions that the peoples of the central savanna attributed to firearms were shaped by preexisting sociocultural relationships and political interests. Without an appreciation of the multiplicity and diversity of such relationships and interests, it is impossible to grasp the logic behind the heterogeneity in patterns of gun domestication that characterized the region. Guns, as later chapters will show, were appropriated differently by different groups, for different were the sociopolitical contexts into which the new technology came to be fitted.

The final objective of this chapter is to introduce nonspecialist readers to the intricacies of the precolonial history of a macro-region that is frequently overlooked in recent general syntheses. It is therefore unashamedly encyclopedic in tone and structure. Since it paints with a broad brush and covers a wide array of areas, peoples, and themes, the chapter might perhaps be regarded as a kind of legenda, to which readers might want occasionally to refer back as they proceed with the rest of the book.

THE CENTRAL SAVANNA TO THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY

This section concentrates on the workings of power in the interior of central Africa before external trading influences began to make themselves uniformly felt in the nineteenth century. Any such discussion must begin by stressing that the vast stretch of open grasslands and woodlands found between the Congo basin rainforest and the Zambezi River offered an altogether unpropitious environment for political entrepreneurs. In this region of “pedestrians and paddlers,”3 state building involved the consolidation of structures and institutions that brought together for regulatory and extractive purposes several descent groups, the main units in central African political relations over the past thousand years or more.4 Commonly, the process was predicated on the recognition of an overarching center of power providing a unifying principle of hierarchy: a chief or a king holding a dynastic name or title. The title was vested in a specific kin group, but its sway was also acknowledged by other lineages, who were themselves the keepers of subordinate titled positions and who might sometimes compete among themselves for the topmost dignity. But this was easier said than done, for the region’s scattered population, vast and easily traversable spaces, and relative scarcity of natural resources magnified the challenges of state building. As John Darwin aptly put it, where “rebelling meant no more than walking away to found a splinter community,” the job of leaders was very tough indeed.5 In the central savanna, even more than elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, the key objective of aspiring big men and state builders was always to establish durable claims over the labor and loyalty of unrelated people. Given the frequent absence of standing armies until the latter part of the nineteenth century, violent conquest was only effective in the short term and when it proceeded alongside less disruptive, “softer” forms of rule. Different societies came up with different solutions to overcome the parochialism of localized descent groups. Invariably, such solutions were related to the ecological specificities of their respective areas.

An early center of political experimentation in the interior of central Africa was certainly located in the Upemba Depression. Archaeological evidence in the form of copper ornaments and small iron bells suggests that processes of social and political differentiation were at work in this comparatively densely populated floodplain on the upper Lualaba River, in present-day southern Congo, since at least the first centuries of the second millennium.6 The rise of wealthy ruling groups in the area may have had something to do with the need to contain inter-lineage competition focusing on access to the floodplain’s rich, but finite, alluvial soils and to its game and fish resources. The same authorities might have also been responsible for coordinating such hydraulic works as were required to keep local economic life viable.7 Experiments in conflict management and political integration on the upper Lualaba are likely to have influenced developments in its immediate surroundings, beginning with what would become the heartland of the Luba “Empire,” the district located between the Lualaba and Lomani Rivers. Alternatively (or additionally), it is also possible to speculate that control over access to scarce trading resources—the salt and iron with which the future Luba core area was endowed—enabled one specific descent group to emerge as locally dominant and to regulate and tax the visits of outsiders seeking the same resources.8

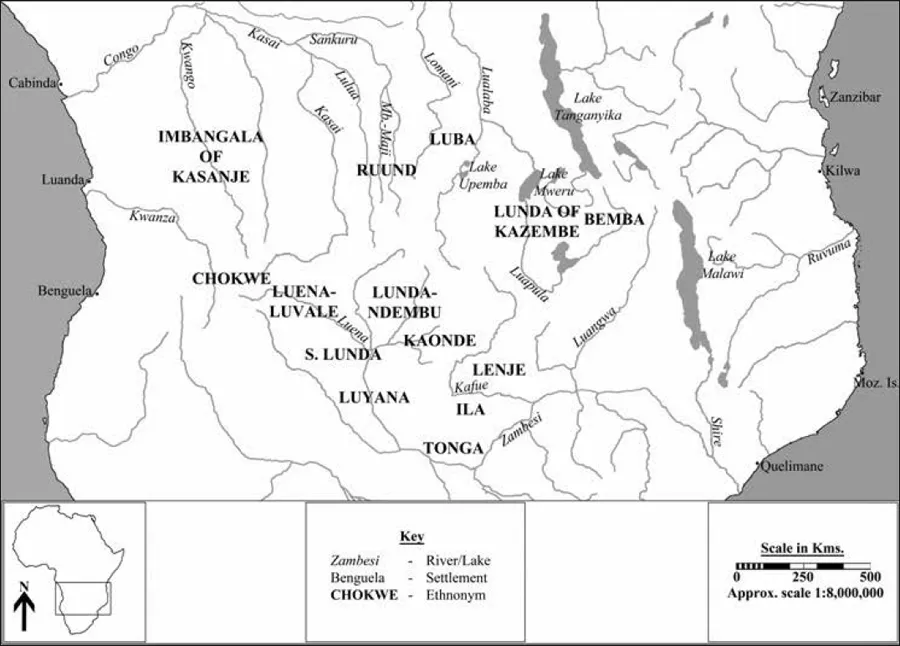

MAP 1.1. The central savanna, c. 1800.

By c. 1700, the time that a Luba dynastic kingdom becomes recognizable in the oral historical record,9 elaborate political hierarchies, revolving around the Mwant Yav (Mwata Yamvo) royal title, had also come into being among the Ruund, to the southwest of the Luba.10 The first substantial written mention of the Ruund state, by the Angolan slave trader Manoel Correia Leitão, dates to 1756. By then, the “Matayamvoa” was being described as a “powerful” conqueror and his followers as “terrestrial Eagles,” raiding “countries so remote from their Fatherland only to lord it over other peoples.”11 Well-known traditions expounding on the marriage between the Ruund princess Ruwej and the wandering Luba hunter Chibind Yirung (Chibinda Ilunga) have frequently been interpreted as implying some form of Luba military conquest or, at a minimum, strong Luba influences on the genesis of the Ruund kingdom. In fact, the linguistic data examined by Jeff Hoover in the 1970s and the objective differences between the Luba and Ruund political systems suggest the playing out of more complex and longer processes of mutual borrowing than the conquest state model allows for.12

The twin institutions of positional succession and perpetual kinship—the Ruund trademark contribution to the precolonial political history of the central savanna—were certainly endogenous innovations.13 Jan Vansina has recently called them “a stroke of genius.”14 Positional succession and perpetual kinship established permanent links between offices rather than individuals, and this meant that the Ruund kingdom “ideally consisted of a web of titled positions, linked in a hierarchy of perpetual kinship” and occupied by people of different background.15 Because these institutions could be adopted without disrupting preexisting social structures, they became wonderfully effective means of imperial expansion. Subordinate hereditary positions could be created for real or honorary sons of a given Mwant Yav; their descendants—no matter who they were, or how far they lived from the Ruund heartland on the upper Mbuji-Mayi River—would continue to acknowledge the original connection, quite independent of the actual biological relationship that would eventually obtain between them and the successors of the Ruund king by whom the appointment had first been made. The integrating effects of positional succession and perpetual kinship were reinforced by another Ruund technique of rule: the recognition of the role of the “owners of the land.” The distinction between “owners of the land” and “owners of the people” was rooted in the ancient political culture of the savanna, but the Ruund systematized it and broadened its application in the context of an imperial strategy. Both in Ruund and Ruund-influenced Lunda states, the leaders of autochthonous groupings were not eliminated or marginalized. Rather, they were granted important ritual prerogatives. Ruund and Lunda political rulers were the “owners of the people,” dealing with the nitty-gritty of daily governance. But, though they were largely excluded from the sphere of temporal government, the “owners of the land” were still accorded a glorified position in the new dispensation. This was partly because they were believed to be in contact with the spirits of their ancestors, who exercised forms of supernatural authority over the districts they had first colonized.16

Thus, between the eighteenth and the nineteenth century, while the Luba sacred kings (Mulopwes) expanded their sway by favoring the accession of select peripheral lineage heads and incorporating them into the bambudye, a cross-cutting secret society which they controlled, the workings of positional succession and perpetual kinship helped bring into being a Lunda “Commonwealth.” The “commonwealth”—a definition which Vansina advocates in preference to the more traditional one of “empire”17—consisted of a network of independent, though interconnected, polities. While their leaders claimed real or putative origins among the Ruund, and though they recognized the Mwant Yavs as the fountains of their prestige, these Lunda kingdoms were not ruled from a single center and did not form a single cohesive territory. The “commonwealth,” in fact, consisted of a series of dominions ruled less by Ruund proper than by elites who had adopted Ruund symbols of rule and principles of political organization.

This Lunda sphere of influence—the extent and workings of which were first reported upon by the famous Angolan pombeiro, Pedro João Baptista, at the beginning of the nineteenth century—was crisscrossed by tributary and exchange networks and covered a large swathe of the central savanna. Its easternmost marches were occupied by the kingdom of Kazembe, founded as a result of the collapse of a Ruund colony on the Mukulweji River towards the end of the seventeenth century and the subsequent eastward migration of a heterogeneous group of “Ruundized” title holders.18 In the west, the holders of the Kinguri, the royal title of the Imbangala kingdom of Kasanje, dominating the middle Kwango River since the seventeenth century, also claimed Ruund origins and—as will be seen below—became the Mwant Yavs’ principal trading partners in the eighteenth century. In the south, smaller Ruund-inspired Lunda polities took roots along the Congo-Zambezi watershed. Early written evidence shows that “travelers” from the Lunda-Ndembu polity of the Kanongesha (“Canoguesa”), near the present-day border between Zambia, Angola, and Congo, were wont to take “tribute” to the Mwant Yavs in the 1800s.19 There is no reason to believe that the southern Lunda of the Shinde and related titles, further to the south, would have behaved any differently.

Political change was not necessarily the result of diffusion or borrowing. Processes of state formation could be more insular and self-contained than in the Luba and Ruund/Lunda cases. The Luyana (later Lozi) state is a good case in point. Its rise owed very little to external influences, but was instead shaped by the complex politico-economic requirements of the upper Zambezi floodplain. Unlike the Upemba Depression (and much of the central savanna), the upper Zambezi floodplain could support cattle keeping. Yet, in other respects, the two ecosystems were co...