![]()

Chapter 1

The mythological film

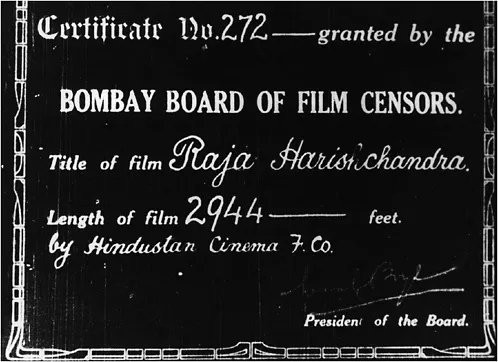

Phalke states: ‘I began the film industry in India in the year 1912’ (ICC III: 869). In fact, the first film was shown in India in 1896 and, although screenings of these and other films were successful, it was seventeen years before Phalke’s Raja Harischandra, the first entirely Indian film, was made.1 However, the intervening years saw Indians working with non-Indians to learn about film making and Phalke’s own training in other visual arts (see below) speaks volumes about the preparation that went into the formation of this cinema. Indian cinema’s roots lie in so many of the arts (theatre, music, painting, photography, literature, dance, story telling) as well as in other aspects of culture that were stimulated by the colonial encounter and the new media that developed during the nineteenth century.

It would be fascinating to have more accounts of the beginnings of Indian cinema but apart from writings by Phalke2 and J.B.H. Wadia’s largely unpublished memoirs,3 we have very little in the way of eyewitness reports. However, we have the extensive and invaluable source of the Indian Cinematograph Committee’s Report and Evidences of 1927–8 (RICC and ICC I–V), which dates from the last years of the silent film in India and give us a great deal of information about the state of the industry, the cinema halls, the audiences and so on from across British India.4 However, since the interviewees had to speak English, we only have the views of the elites and we know little about what the ‘ordinary person’ thought of cinema. We know which genres certain segments of the audience enjoyed but we do not have any information about why they enjoyed them and what they thought of them. We can reconstruct some of these views from advertisements in newspapers and specialist magazines but the former often ignored cinema while many of the latter publications have not yet been made publicly available, if they exist at all.

Reading the ICC Evidences, I was struck to find that so much of the discourse around cinema today in India is similar to that of almost a hundred years ago. Why has Indian cinema, which itself changed so much, been trapped by this discourse, which perceives it as backwards, inferior to the west, in need of censoring to ‘protect’ the lower classes, and in

financial crisis and so on? Why does it focus on the failings rather than the success? Statistics quoted in Shah (1950) show the inexorable rise of cinema in India (1950, Ch. 3), although it remains relatively small in proportion to the population in comparison with the United States and Europe. However, by 1939 cinema was the eighth largest industry in India and the third largest cinema in the world (Shah 1950:60). It has an audience throughout India, albeit concentrated in the urban centres, and was distributed in areas where the Indian diaspora were settled (East Africa, South Africa, Fiji, Mauritius, Federated Malay States, Iraq and West Indies (Shah 1950:55).

Much academic writing on Indian cinema focuses on it as a major vehicle for nationalist discourses, but, although one or two of the interviewees refer to the nationalist movement and several film makers (such as J.B.H. Wadia) were actively involved with the freedom struggle, this topic is rarely mentioned in the Evidences. Indeed, the names of many of the companies (Imperial, Minerva) and the names of the cinemas (Albert, Coronation, Wellington) suggest a different view and I shall reassess the importance of nationalism in looking at these films.

As nationalism, cinema is often said to be a new religion (Lyden 2003). While there are striking shared features, the analogy should not be pushed too far.5 Nonetheless, these features cannot be ignored and one of my concerns is to examine the universal and particular features of cinema in India. Hindu and Indian are often conflated (sometimes to dangerous effect), but given that Hinduism is almost exclusively associated with South Asia and its diaspora, this makes the analysis of the culturally particular relatively straightforward in the case of the mythological film.

The mythological among other genres

As feature films began to form into genres in the US, the religious film developed from the filming of Passion Plays6 to Cecil B. DeMille’s big-budget productions such as The Ten Commandments (1923) and The King of Kings (1927).7 DeMille’s much-quoted remark that ‘God is box office’ was certainly true of these and other films, whose attractions included great spectacle and often special effects for miracles as well as providing audiences with religious experiences.

The first films made in India before Phalke were by Harishchandra Sakharam Bhatavdekar (1868–58), better known as Save Dada. He made several shorts including one of a wrestling match in the Hanging Gardens, Bombay and another on monkeys (both 1899), as well as some actualities including the return from Cambridge of a famous mathematician (Sir Wrangler Mr R.P. Paranjpye, 1902) and the celebrations of the coronation of Edward VII (Delhi Durbar of Lord Curzon, 1903);8 while Hiralal Sen (1866–1917) shot plays from Star Theatres and Classic Theatre, Calcutta from 1898. However, the first all-Indian feature film, Raja Harischandra, was a ‘mythological’, a genre which is unique to India.9 The mythological has been given prominence in India as its founding genre and because of Phalke’s eminence (and the survival of so much of his output) but it has always been perceived to be in decline and many other genres were popular during the silent period in Bombay including the stunt or action film, the historical,10 the Arabian Nights Oriental fantasy (see Chapter 3) and the social (see Chapter 4). (Other regions preferred different genres; for example Bengal, with its rich literature, preferred more intellectual and social themes drawn from novels or filmed stage plays.)

Some sources give early genres as mythological, religious, historical and stunt (Shah 1950:43), with some distinguishing the mythological from the folkloric while others regard them as the same, and yet others separate the devotional and religious (Shah 1950:116). The RICC (p. 34)11 notes the major genres as mythological or religious, historical and social dramas, before saying that there are two or three companies which specialise in mythological films.12

The advertisements of the early periodicals are not consistent in their generic categories. For example, Variety Film Service, in its magazine advertisements, lists its 1931 and 1932 releases as: Special exclusive (included Biblical themes such as Sodom and Gomorrah, Judith and Holophernes); social; jungle; Oriental, romantic (including Sampson and Dalilah, INRI) and semi-Oriental; stunt and fighting.13 The Gujarati journal Mauj Majah during the 1930s refers to pauranik films, which could mean literally from the Puranas (Hindu myths) or could mean more broadly mythological/ legendary. The Hindi journal Rajatpat of the late 1940s has adverts for samaajik (‘social’), dhaarmik (‘religious’), aitihaasik (‘historical’) and stunt.

Kusum Gokarn devotes a whole chapter of her study to a discussion of the discreteness of the mythological and devotional to conclude that there is just one genre (Gokarn n.d.: 86–92), the ‘religious’ film, but I am maintaining the division here between the two types as it seems to me that they are differentiated by their production houses, their style and content, their advertising and reception.

Although the genres of early Indian cinema were recognised by the film makers and the audiences, no generic category is watertight and Indian cinema’s notoriously fuzzy genres are even more porous than most. However, I define the mythological, the founding genre of Indian cinema, and one of the most productive genres of its early cinema, as one which depicts tales of gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines14 mostly from the large repository of Hindu myths, which are largely found in the Sanskrit Puranas, and the Sanskrit epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. The early mythological genre drew on a wide range of the modern and the traditional to create its own distinctive hybrid style, with strong connections to nineteenth-century Indian popular or middlebrow public culture as well as with other forms of cinema that were emerging at the same time in other places in the world.

Some films blur these generic boundaries, notably the much-discussed Jai Santoshi Maa (see below), which has many elements of the social (the heroine is fictional and lives in some vaguely contemporary world) or the devotional (the film concentrates on her devotion to the goddess), but, I argue, the actual manifestation of the gods in human form separates it from the social where the miraculous is usually shown as acting through an image or other medium, and is distinguished from the devotional, which focuses on the life of a human devotee who is presented in historical time. Of course, for many devotees of Rama, the yuga (aeon) in which he was on earth is historical time and he continues to live in the present time, but I am referring to the narrow, academic definition of historical time. In many devotional films, the historical figure of the devotee enters into divine time and space, so Narsi Mehta witnesses the Vrajlila (episodes from Krishna’s pastoral idyll), but the film’s focus is on Narsi and his devotion. The mythological is defined by the stories of the gods and goddesses – or heroes and heroines – themselves, so Jai Santoshi Maa also tells the story of the goddess herself, how she is born and how she gains recognition among the older goddesses.

The mythological genre is defined largely in terms of its narrative. It may recount the story of gods and goddesses, whose oldest versions we have in the Sanskrit Puranas,15 which have been retold over the centuries.16 Each Purana contains the stories associated with particular deities, so Krishna’s lila or ‘life’ is told in the Bhagavata Purana. However, the films have drawn more closely on India’s two great epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.17 While these texts are traditionally the work of single authors (Vyasa and Valmiki respectively), historical analysis finds them to be the result of oral composition and as such there is no original text of either, nor is there one single, correct version but there are many versions of each epic (Richman 1991). Their origins are at least non-Brahminical, judging from the names of the characters and given that the Ramayana story is first found in Buddhist sources. However, they have been fully incorporated into Hindu religious literature, as key characters are seen as incarnations of gods, the Mahabharata now being called the ‘fifth Veda’. Although these Sanskrit texts are the oldest extant versions we have of these stories,18 and are still sources of powerful narratives and imagery, they have no claim to primacy and they should not be read as ‘original’, because of the plurality of traditions in India. We should also note that the Sanskrit tradition is predominantly the culture of the male and the high caste, while other tellings are found among women, Dalits and other subaltern groups. There are still many other tellings of episodes from these epics, whether sung by bards, performed in plays, depicted in comics, made into films and television dramas or simply told as household tales.

The core of the Mahabharata was composed around the second or third century BC, although some sections are much older. Various episodes, stories and even whole texts (such as the Bhagavad Gita) have been interpolated, with it reaching its present form of around 100,000 stanzas, some time around the fourth century AD. The central story is the dispute over the thron...