![]()

1

SEOUL

A Korean capital

Sharon Hong

In the midst of rapid urbanization in Asia, urban landscapes are changing rapidly to the point of non-recognition. As Asian cities embrace projected futures, journeys toward them often come at the expense of rich histories built into the urban fabric. In Seoul, Korea, rapid urbanization in the twentieth century nearly destroyed 600 years of history (Kim 2010). A significant loss of this traditional urban fabric in modern Seoul is easily equated with the degradation of place and the loss of traditional culture. However, the experience of Seoul reveals, through the process of modernization – often viewed as Westernization and the erasure of the traditional society – that culture is not lost but evolves.

Culture is not fixed, and its inherent value is lost when grasped too firmly. Cultures transform by accepting and incorporating elements from other cultures and omitting aspects of their own. Urbanization in Seoul has not always involved the conscientious effort to promote local culture through the built form. In fact, Seoul’s agents of urbanization in the twentieth century were intent upon erasing the urban legacy left by their predecessors. Each successive power and generation learned to naturalize seemingly incompatible “urbanisms” into a localized modernity, rather than falling into a process of acculturation in an abstract space, or by Westernization alone.

The “modern” city of Seoul comprises deceptively similar elements of a modern Western city. The current Mayor of Seoul, Oh Se Hoon, is aggressively promoting high technology, design, and tourism. Seoul is not immune to the global “creative city” movement, a concept given salience by high-profile urbanists from the West like Charles Landry and Richard Florida. The current propensity for “starchitecture” following the “Bilbao effect” (catalyzed by Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain) may also be found in Seoul with the development of the Dongdaemun Design Park and Plaza designed by Zaha Hadid. Nevertheless, local culture is resilient in spite of a tragic history of colonialism, civil war, and aggressive industrialization. That Seoul has maintained a strong sense of local culture in the midst of ambitious development plans is a testament to how Asian cities can change their “traditional” form based in local values.

This study highlights that Seoul is an Asian model of urban transformation and development. Mainstream literature on Seoul focuses on the rapid pace of development at the expense of local culture brought about by invasive external factors. While scholars such as Kim (2010) illustrate how democratization of Korean society and the commercialization of Seoul’s main streets continue to transform a traditional “anti-” urban fabric, this metamorphosis is still building upon an existing street network laid out using traditional pungsu values, as illustrated by Valérie Gelézeau (1997). In the following pages, I will first outline the history of the relationship between culture and the built form in Seoul. In doing so, I argue that the city’s modernization has been influenced by colonial and Western forces, but still remains rooted in distinctly East Asian urban practices. I go on to argue that the current direction of the Seoul Metropolitan government’s urban regeneration initiatives privileges cultural memory, public realm enhancement, and ecological benefits. Although competing ideologies of neoliberalism and commercialization appear to be obstacles, this promises the development of a local modernity, as highlighted by scholars such as Kusno (2000) and Hosagrahar (2005).

“Paradoxical Seoul”: traditional urbanism

Seoul is a historical city with a past stretching back over 600 years. Its urban form remained virtually untouched in the first 500 years of its existence as the capital of the Chosun Dynasty (1392–1910). While the process of modernization in European cities occurred over several centuries, today’s ultramodern Seoul seems to have emerged from the rubble of the Korean War (1950–1953) half a century ago. Tourist guides, like Lonely Planet, advertise the city as “Paradoxical Seoul,” where “beneath the manic modernity, Korea remains arguably the most Confucian nation in Asia. Like nowhere else in Asia, younger generations of Koreans, particularly in Seoul, still feel (and do consider themselves devoted to) the firm pull of culture and tradition” (Robinson 2006: 7). Despite drastic changes in the twentieth century, modern Seoul maintains a distinguishable local identity.

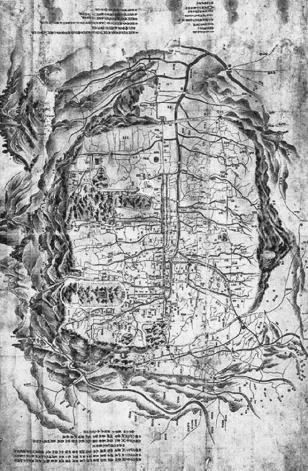

Seoul was founded on the tradition of pungsu (fengshui in Chinese), adapted by King Taejo, first king of the Chosun Dynasty (Ryu 2004). According to pungsu principles, Seoul was laid out in accordance with the waterways and geographical configuration of the surrounding mountains. There are two major types of pungsu-based landscape designs for mountainous regions, and Seoul was formed according to the “convoluted patterning” (Jangpung-Deuksu), often related to promoting military security and rice production. The traditional practice of pungsu is a fusion of natural and cultural considerations in the processes of land evaluation and development. Forestry professor Sun Kee Hong and colleagues (2007: 222) of Kookmin University explain that “fengshui theory views biophysical entities through the lens of empirical cultural knowledge, so that holistically-meaningful sustainability is melded with cultural [and] historical aspects of the human environment.” Pungsu provides the theoretical foundation for the modern practice of holistic landscape ecology in Korea and remains one of the Chosun Dynasty’s most significant legacies on Seoul’s urban form. A period of exponential growth and disregard for natural and cultural heritage replaced pungsu with the “development-first” principle of the developmental-state era.

FIGURE 1.1 Painting of late eighteenth-century Seoul

Source: Hong et al. (2007)

Colonial and “reactionary” urbanism

The year Japan colonized Korea (1910) marks the beginning of a dramatic shift from traditional urbanism to modernization. In his study on modernism and development in Seoul, Hyungmin Pai (1997) explains how colonization replaced traditional practices, like pungsu, with rational techniques from the West underpinning the redevelopment and expansion of urban areas. For example, the German practice of Umlegung, adapted by the Japanese, introduced a systematic repartitioning of lots in the city to efficiently exploit land resources. Rather than adding to the existing fabric, Japanese colonization brought a new morphological order centered on large boulevards and European-style buildings. The massive colonial government building erected in the place of Gwanghwamun (Seoul’s most prominent gate in the wall circling the old city) overwhelmed the Gyeongbok palace (the political and cultural center of the Chosun dynasty). This period of colonial urbanism introduced a new scale defined by monumental artifacts, conflicting with Seoul’s traditional urban structure. Locals viewed modernization as a foreign invasion – something not Korean. In Pai’s (1997:113) words: “It seemed to many that colonialism, urbanization, capitalism, and modernization were in fact one and the same.… To be on the side of modernization was to be a Japanese sympathizer and a traitor.”

The legacy of colonial urbanism continued even after liberation in 1945. Seoul experienced a period of “reactionary urbanism,” following nearly half a century of colonial rule and the devastation of the Korean War. The movement was led by Park Chung Hee, whose military dictatorship lasted for nearly two decades (1961–1979). A post-war redevelopment strategy began with the state-led clearance and bulldozing of slums which had proliferated after the war, bringing refugees from around the country into Seoul (Lee 2000). “Bulldozer Mayor” Kim Hyun Ok, appointed by Park in 1966, bulldozed through mountains and over rivers to build roads while proclaiming the modernist dictum: “the city is lines” (Ryu 2004:3). Park Chung Hee-style urbanism in Seoul continued the monumental scale of colonial urbanism.

The urban regeneration under Park also reclaimed and modernized Seoul for the Korean people. Park’s regime is often considered the originator of Korea’s highgrowth era, marked by uncontrolled development and supported by the singular focus to industrialize the country. Nevertheless, promotion of traditional culture was a priority. The official discourse of the 1960s and 1970s dictated that, “while culture must be national, ethnic, and traditional, development must have a modern face” (Pai 1997:121). Park’s nationalist regime took over the former headquarters of the Japanese government and reformed Sejong-no (a wide boulevard introduced during colonial rule) into a representation of the nation. Nationalist cultural policies from the military regime encouraged constructing national museums for art and culture. The architectural competition to design the National Museum and Sejong Cultural Centre required that designs emulate traditional Korean architecture and incorporate elements from existing ancient monuments. Insadong (still one of the largest clusters of Korean art shops and teahouses in Seoul) experienced its heyday during this period (Kim 2007).

The return of Gwanghwamun to the center of Gyeongbok Palace, in front of the former colonial government building, spurred a wave of cultural activity (Pai 1997). As the historic, cultural, political, and economic center of Seoul (and in fact the country as a whole), Gwanghwamun accommodated many public art museums, especially in the 1970s when Koreans began to pay more attention to their traditional culture (Kim 2007). Ironically, during the time of Park’s reactionary urbanism, Korea experienced a revival in traditional culture. Traditional representations from the past were blended into the modern environment, transforming both.

FIGURE 1.2 Sejong-No in Seoul (2010)

Development and culture were disconnected during this period, due to tensions between modernity and tradition. Pai (1997: 121) describes this tragic separation of “modern” and “tradition”:

On the one hand, there is a discourse in which culture is a thing that can somehow exist on its own: reproduced, for example, in the form of a museum secluded in a palace, or in the forced preservation of residential neighbourhoods. On the other, there is a tortured modernism that allows itself to become the ideological face of development.

This devaluation of culture resulted in the loss of much of Seoul’s traditional urban fabric. As it focused on monumental architecture, the military regime overlooked everyday “traditional” practices and spaces, demolishing ancestral temples and sacred territories in the name of modernism. While modernist urbanism took hold as the ideological face of development in the city, science and engineering were considered to be formless and timeless “culture-free” tools. This mandated architecture to express rationalism and technology, rather than cultural values and tradition.

Modernist urbanism

The Korean intellectual context during this time was greatly influenced by Western urbanism, particularly the modernist theories of Le Corbusier. Western urbanism was imported into Korea through prominent architects like Kim Joong Up who worked in Corbusier’s studio during the 1950s (Gelézeau 2007). A 1970 article published in the Journal of the American Planning Association provides a snapshot of the international perception of modernization in Seoul as a process of acculturation of the urban landscape through the imposition of foreign ideas. According to Meier (1970: 392), “The acceleration in urban and regional development is ascribed to [a] ‘Japanization’ stage superimposed on the American-led international influence of Korean affairs.” As modern building complexes and apartments became the new norm during the developmental-state era, Seoul’s embracing of Western urbanism appears as a self-negation of traditional urbanism.

As the country industrialized and transformed into a high-technology society, modernist urbanism dramatically changed Seoul’s traditional urban fabric during the 1980s. Urban redevelopment policy in the old part of the city built over traditional forms, replacing them with high-rise complexes and Western-style apartments. From 1981 to 1982, the Olympic bid was the premise for the national government’s continued policy of slum clearance and redevelopment in order to project a modern image of Seoul to the world (Douglass 2008). From the late 1980s onward, steep increases in modern apartment buildings completely transformed the image of the city. By 2006, modern apartments represented 53 percent of the housing stock, up from 4 percent in the 1970s. Single-family detached homes, the traditional hanok, dropped from 88 to 25 percent of the housing stock during the same period (Gelézeau 2007). By the turn of the twenty-first century, modern apartment buildings replaced traditional forms to become the norm for housing in Seoul.

Nevertheless, Gelézeau’s (2007) study and extensive fieldwork on modern apartment buildings in Seoul reveals that the city’s modernization was not a simple negation of traditional culture, nor an annihilation of the traditional urban fabric. Rather, she argues, superimposition of modern structures on the traditional organization of land means that Western modernist urbanism was not a direct transfer of Western practices, but an adaptation of Western urban theories to the Korean context. To solve the real challenge of land scarcity and exponential growth in Seoul, modernist urbanism in Korea was a synthesis of two irreconcilable theories in the West: American planner Clarence Perry’s concept of the neighborhood unit with low-rise detached homes, and Corbusier’s high-rise towers in the park (Gelézeau 2007). In one sense, this combination of architectural modernist and garden city principles may be considered emulation. Nevertheless, the adaptation of Western urbanism to help solve Korea’s urban challenges created a distinctly Korean model of modernist urbanism.

Despite the large-scale and widespread development of modern apartment buildings, Gelézeau (2007) argues that the foundations of the city continue to be based on traditional pungsu principles established during the city’s first 500 years of its existence. The street network remains largely influenced by the notion of the peripherality of royal palaces to the natural topography as opposed to the notion of centrality in traditional occidental cities, similar to the public square and Roman forum. The resilience of Seoul’s traditional urban framework is attributed to the persistence of a street network based on pungsu principles of connectivity, plus a network made up of the stream, mountains, village, and human habitation (cf. Hong et al. 2007).

Moreover, Gelézeau (2001) challenges the tendency to equate the improvement of housing conditions with technical advances from the West. Seoulites themselves often contrast the modern comfort of Western-style apartment complexes with the traditional hanok typology, which symbolizes a period of “underdevelopment” and poverty. Nevertheless, Gelézeau demonstrates that technological advances such as central heating in these complexes is a predominantly Korean advancement of the ondol heating system, an ancient form of central heating transmitted underground, in the traditional house. Although the idea of central heating may be imported, the combination of this local technology – or vice versa – makes it unique to Seoul.

Gelézeau’s (2001) study also reveals that the organization of space within modern apartments reflects the layout of traditional hanok and courtyard forms. For example, balconies in modern apartment buildings do not act as an exterior, recreational space separated from indoor household activities, as they do in the Western prototype; rather, balconies of Korean apartments take on functions that were previously devoted to the courtyard in the traditional Korean home, such as washing and drying clothes, and storing bulk domestic products and food. The balcony of the modern apartment exists as an urban form of the traditional courtyard. In this way, Gelézeau (2001) questions the simplistic dichotomies between “tradition” and “modernity,” “Western-ness” and ”Korean-ness.” She identifies the modern apartment as a contemporary symbol of its distinct identity, rather than a sign of Seoul’s acculturation. Her work alludes to the emergence of hybrid (third) spaces in Seoul, where modern forms are adapted for traditional uses and traditional forms take on new uses. These combine to create new composites.

Hybrid urbanism

The further democratization of Korea, including Seoul’s first local elections for mayor and heads of the city’s 25 districts (‘gu in Korean) in 1995, made room for community-led development (Kim 2006). In the same year, a citizens’ group called “Citizens’ Solidarity for Sustainable City” was established, and demanded alternative approaches to development that respected traditional culture and the natural environment (Douglass 2008). As the proliferation of modern apartment buildings peaked, creating a new urban frontier, the democratization facilitated a small but notable return of interest in traditional architecture and urbanism in the late 1990s. Until then, the modernist ethos that dominated the city had been largely unchallenged. A new era of hybridity taking form in Seoul means that “the uneven movement of social development” or “the coexistence of realities from radically different moments of history” is no longer embarrassing (Ryu 2004: 7). Within this perception, mom-and-pop stores can exist alongside franchised convenience stores, European restaurants next to Korean folk tavern...