- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The City in South Asia

About this book

The macro-region of South Asia – including Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka – today supports one of the world's greatest concentrations of cities, but as James Heitzman argues in the first comprehensive treatment of urban South Asia, this has been the case for at least 5,000 years.

With a strong emphasis on the production of space and periodic excursions into literature, art and architecture, religion and public culture, this interdisciplinary study is a valuable text for students and scholars interested in comparative history, urban studies, and the social sciences.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 The ancient heritage

In 1982 I attended a scholarly conference in the city of Madurai where historians delivered professional papers on the study of early South India. One of the papers concerned Lemuria, described as a continent that once existed south of Kanyakumari, the southernmost point in India, but which sank beneath the sea in prehistoric times. Although this concept seemed a bit far-fetched to me, there was no difference between the audience’s public reception of this paper and that accorded to the other presentations at this conference; everyone treated it as just another problem in the ‘normal science’ of the historical discipline. Subsequent exposures to Lemuria revealed that the idea surfaced among nineteenth-century geologists attempting to explain global distribution of paleospecies through hypothetical land bridges, then enjoyed a brief currency among early ethnographers interested in the original homeland of homo sapiens, and finally became transformed during the twentieth century into a primordial land whose inhabitants could be accessed through spiritualist channeling. In Tamil Nadu, however, the existence of this lost world has achieved the status of official history. As the continent of Kumarikantam, it has appeared in the curriculums of state-run Tamil-language schools, served as the subject matter of comments in the state legislature and a film funded by the state government, and generated a substantial body of literature that has described and mapped it in great detail. Sumati Ramaswami, in her study entitled The Lost Land of Lemuria (2004), contextualizes the survival of this fabulous land, inaccessible now because of oceanic catastrophe, as an exercise in the modern productivity of loss, a reenchantment of a disenchanted reality, an attempt by subaltern groups to reclaim center stage within an altered construction of the past.

As a land of hunters and gatherers living in a state of nature or as a bounteous land of farms, fields and mountains, Kumarikantam would conjure the sensibility of nostalgia typical of lost utopias. But it is much more: it is the source of urban life. Passing references in the two-thousand-year-old Tamil Sangam literature and later commentaries describe the compilation of the earliest Tamil literary corpus in the Madurai we know today but mention also that two earlier compilations had occurred in cities named ‘southern’ Madurai (Tenmadurai) and Kapatapuram, which disappeared under the sea. Heroic efforts of the Pandyan kings preserved some of the advanced knowledge produced in these early metropolises, these centers of trade and industry, and transmitted fragments of language and culture to posterity in historical times. Kumarikantam is not simply the homeland of the entire human race but the heartland of cities and thus civilization, which retained a tenuous hold in Tamil Nadu while spreading throughout the world. The ‘scientific’ character of these assertions receives support from regular references to the (now discarded) geology of sunken continents, more recently supplemented by global warming and the example of the 2004 tsunami, and archaeological discoveries of submerged structures just offshore at the sites of Pumpuhar and Mahabalipuram (the latter revealed by the tsunami). If only more scientific research were devoted to underwater exploration off the southern coast of India we would discover more clues to the lost continent and thus prove the validity of the textual references in early Tamil literature! In this sense the Kumarikantam phenomenon resembles the lost continent of Atlantis – site of another super-urbanized and now-lost civilization – and, closer to home, the lost port of Dwaraka, the home of Krishna according to North Indian Sanskrit texts, where recent discoveries of underwater structures have stimulated paroxysms of cultural pride.

The more prosaic treatment of early urbanization in South Asia presented in this chapter traces permanent settlements going back about 8,000 years and brings the story of the city up to about 1,000 years ago. The early phases of the discussion here will please, I am afraid, only professional archaeologists and historians who describe urbanization as a phenomenon appearing about 2,500 bce and known only through its physical remains located primarily in Pakistan and northwestern India. The chapter then examines a ‘second’ urbanization that became consolidated by about 500 bce and became the basis for all subsequent urban forms in the subcontinent. This second urbanization peaked just after the beginning of the Common Era and, although attenuated in some regions by the fifth century, became the foundation for a reorganized urban system connected with the growth of regional kingdoms and an expansion of Indian Ocean trade. By the tenth century, at the latest, this system underwent a significant amplification and slowly evolved into the substratum of today’s gigantic urban configurations. The chronological framework presented here will hopefully inform those interested in evaluating the historicity of lost cities in South Asia, whether they lie under the sea or, like Ayodhya, on the land.

Archaeology, literature, and early cities

The discerning traveler through the northern plains of South Asia may notice the periodic appearance of mounds amid cultivated fields or near (sometimes under) villages and towns and, in a moment of reflection, ask why these anomalous features of higher elevation should exist within a region of relatively low relief. In many cases, these hillocks are the result of human activity; they are what archaeologists in the Arabic-speaking world call tells, consisting of the accumulated debris of many human generations living on one site, pulling down the decaying walls of old mud-brick homes, mixing them with accumulated debris and building new houses above them. They are the remains of central places – villages, towns, and cities – that were important to people in the more distant past.

Few appreciate the antiquity of the agrarian and urban settlements represented by these mute mounds which people today plough and plant with crops, pillage for soil and bricks, or tread when they cross their doorsteps. Even the first modern historians of South Asia, while cognizant of the archaeological material lying near at hand, subordinated physical culture to textual analysis. During the nineteenth century, when British scholars oversaw the assembly of the historical disciplines, the model for archaeological reconstruction was to begin with references in textual sources and then correlate them with information gleaned through ground surveys and excavations. The most important chronological baselines were the ministries of Gautama, who established Buddhism, and his immediate predecessor, Mahavira, who promoted Jainism; information gleaned from the texts associated with their religious traditions suggested that these men lived around the middle of the first millennium bce. The first Director of the Archaeological Survey of India, Alexander Cunningham (1814–93), enjoyed considerable success in following references from such textual materials, or from travel accounts such as that of the seventh-century Chinese monk, Xuan Zang, in order to identify specific mounds with places appearing in literary sources. The early results of this research clearly indicated that a society of considerable urban complexity and sophistication existed in what are today northern India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh about 2,500 years ago.

The Vedas, which were originally hymns recited by sacrificial priests during fire sacrifices and which were transmitted in purely oral form almost unchanged for many generations, provide an alternative avenue for understanding the early history of South Asia. Comparative linguistics in the nineteenth century suggested that the Vedic corpus that has come down to us in written format may date back to a period between 1,500 and 1,000 bce. The world presented in the Vedas, located mostly in the Punjab region of India and Pakistan, is distinctly non-urban, although the hymns contain references to impermanent strongholds of mud, stone and timber stormed during military conflicts (Rau 1973). Various bodies of texts viewed as appendages of the Vedas, such as the early Upanishads composed in the early-first millennium bce, measure wealth in cattle and do little to change our vision of northern India as a complex but non-urbanized world of village farming communities and forest.

The Epics called the Mahabharata and the Ramayana – the former (like Homer’s Iliad) describing a great internal war between two coalitions of aristocratic warriors, the latter (like Homer’s Odyssey) describing the exile and adventures of a warrior prince – provide deep insights into the culture and social organization of northern India and Pakistan as far back as the late-second millennium. We must exercise caution, however, in our analysis of these tales transmitted orally for hundreds of years, full of interpolations and anachronisms, and without archaeological evidence to corroborate their standardized presentation of cities (Lal 2002). The main characters in the Epics pursue power, glory, honor and pleasure rather than the control of more mundane resources gathered from the agrarian economy or commerce. The heroes value portable, disposable wealth: prestige goods made from metals or other rare items obtained through extractive activities; the skilled services of attached laborers and dependent women; animals such as elephants or, more typically, cattle. The problems of administration typically lie deep in the background, except for the Santi Parvan of the Mahabharata, where the dying Bhishma, resting on a bed of arrows, dictates a managerial treatise that is obviously a later insertion. The religious rituals supported by the warrior (kshatriya) elite, enacted by brahmana ritual specialists, do not occur within permanent structures dedicated to deities but take the archaic form of sacrifices performed within temporary, consecrated enclosures. Political organization, described by historian Romila Thapar (1984) as lineage rather than state and by George Erdosy (1995: 99) as ‘simple chiefdoms,’ revolves around specific named centers. When the Pandava heroes of the Mahabharata break off from the main lineage of the Kurus to found their own kingdom, they establish their capital at Indraprastha, described in glowing terms as a shining metropolis. Yet when their rivals invite the Pandavas back to the original capital, Hastinapura, for a gambling festival, the gaming takes place in a more standard venue – an ornately decorated, temporary pillared hall assembled from wood, textiles, and other perishable materials. And everywhere we find the nearby forest, the site of so many royal adventures and the regular destination of exiles. When Rama, the hero of the Ramayana, departs from his capital of Ayodhya (portrayed as another metropolis by the bard Valmiki) he and his companions quickly find themselves in the forest and they remain there during wanderings through central and southern India except for sojourns in the hermitages of ascetics, the rude fortifications of various animal kingdoms, or the fantastic capital of the demonic enemy, Ravana. The heroes and the sages of the epics live in a society exhibiting technological sophistication, occupational specialization and status differentiation, but we might question the scale of urbanization in a world where the omnipresent wilderness, the struggle between legitimate settlement and untamed nature remain primary narrative devices.

Basing their analysis primarily on textual corpuses and associated archaeological surveys, scholars at the beginning of the twentieth century viewed the urban history of South Asia as beginning around the time of the Buddha preceded by a gestation period of indeterminate length shading into a semi-nomadic mode of subsistence during the second millennium bce. But this perception was about to change.

The first urbanization: Harappan civilization

Explorations in what is now Pakistan during the late-nineteenth century conducted by scholars around early Buddhist monuments or by construction crews obtaining building materials yielded stone seals featuring animal motifs and an unrecognized script. The first structured excavations during the 1920s at Harappa and then at Mohenjo-daro yielded artifacts that resembled items uncovered during contemporary excavations in Iraq (old Sumer) dated to the third millennium bce. These discoveries stimulated the growth of an entirely new field in South Asian archaeology dedicated to the study of what came to be known as the Harappan (after one of its most important sites), Indus Valley, or Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization (after the two major rivers along which its sites clustered). The nomenclature of civilization applied to this extensive archaeological complex derives not only from its literate or proto-literate character but also from the indisputably urban character of its major sites.

Excavations during the 1970s and 1980s at Mehrgarh in Baluchistan provided convincing proof that the rise of agriculture and village life, evolving into more complicated forms of urbanization, was not the result of diffusion from the west but originated in the creativity of South Asian peoples (Jarrige et al. 1995). Mehrgarh lies at the foot of the Bolan Pass, along an ancient trade route allowing travel to the highlands of Afghanistan and Iran and also to the plains of southern Pakistan, with relatively easy access to a variety of ecological niches. Archaeologists discovered here a continuous record of habitation dating back to a pre-ceramic culture in the early-seventh millennium bce which makes this site contemporaneous with Çatal Hüyük in Turkey (Mellaart 1967) and Jericho in Palestine (Kenyon 1970), several of the world’s oldest known settlements. At that point the inhabitants of Mehrgarh were already constructing permanent structures of mud bricks including houses and storage facilities designed to preserve barley, gathered by semi-nomadic groups using flint sickles and relying on hunting for part of their subsistence. The subsequent story of this site includes the evolution of increasingly sophisticated ceramic technologies, domesticated animals and more permanent settlement structures. By the late-fifth millennium the inhabitants utilized copper, manufactured wheel-thrown pots, and produced artistically fired beads. By the fourth-third millennium bce, permanent settlements and cultivation, possibly with irrigation facilities, had replaced traces of seasonal habitation. Wheat and grapes were important crops. Traces of large-scale pottery production suggest the presence of a multi-site marketing system. Large numbers of terracotta human forms appear in and around house sites. Extensive terracing and large retaining walls indicate a movement toward monumental public architecture. Trans-regional trade seems to have been important at Mehrgarh even from its earliest phases (revealed by the presence of shell ornaments coming from the ocean, 500 kilometers distant). The later phases of occupation link directly with nearby sites such as Nausharo yielding Harappan artifacts, thus providing a sequence from the very beginnings of settled life through the first urban urbanization in South Asia.

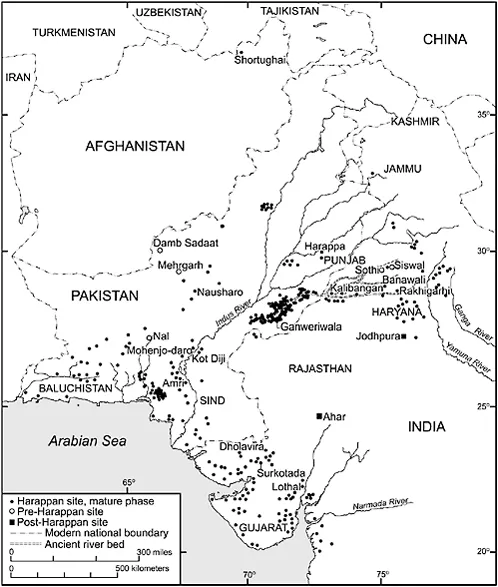

Archaeologists have identified hundreds of sites where pre-Harappan village farming communities developed the complete range of technologies (including traces of monumental walls) that would give rise to Harappan urbanization. In addition to Mehrgarh four such artifact assemblages have been identified, each associated with their primary sites: Amri and Nal; Kot Diji; Damb Sadaat; Sothi and Siswal (see Map 1). Investigators now describe a pre-Harappan period beginning in the late-fourth millennium bce, when changes were occurring within multiple cultures that prepared the ground for the complexity of the mature Harappan phase between 2600 and 1900 bce. The transition to the mature phase seems to have occurred rapidly, perhaps within only a few generations (Possehl 1999; 2002: 50–3).

Map 1 Sites of the mature Harappan phase, ca. 2600–1900 bce. Adapted from Possehl 2002.

More than 1,000 sites display the cultural characteristics that we associate with the mature Harappan Civilization. They exist in all parts of Pakistan south of Kashmir, in Gujarat, Haryana, Jammu, Punjab, and Rajasthan in northwestern India, and even along the Amu Darya in northern Afghanistan. Most of the locations remain small, constituting village sites; if the average size of settlements during the early Harappan phase was 4.51 hectares, it increased to only 7.25 hectares during the mature phase (Possehl 1999: 555). The largest sites, however, are quite big. They include Mohenjo-daro (with a city core of about 100 hectares, and suburbs possibly covering more than 200 hectares) in Sind; Harappa (more than 150 hectares) in the center of Pakistani Punjab; Dholavira (between 60 and 100 hectares) in Gujarat; Ganweriwala (82 hectares) in Pakistani Punjab near the border with Rajasthan; and Rakhigarhi (between 80 and 105 hectares) in Haryana (Smith 2006: 109).

The region called Cholistan, lying in the southeastern part of Pakistan’s Punjab province, is among the most thoroughly explored regions of the Harappan civilization. Today this is an arid ecosystem, a northwestern extension of India’s Thar Desert, but ground surveys and aerial photography reveal that a major river system once flowed here. Between 3,500 and 1,300 bce there was enough water to support a flourishing complex of village farming communities evolving into a four-tier hierarchy of settlement sizes. During the first centuries of occupation, nomadic occupation roughly balanced the number of more permanent agricultural settlements. By the time of the early Harappan phase (3100–2500) permanent settlements comprised 92 percent of all extant sites while nomadic campsites had shrunk to only 7.5 percent. After 2500, during the mature phase, out of 174 identified sites (most of them small villages) 45 percent were purely industrial locations for the production of bricks, pottery or metal objects while 19 percent of habitation sites also included kilns for commodity production. During this phase Ganweriwala, the pinnacle of the settlement hierarchy, became two closely associated mounds, today rising to a maximum height of 8.5 meters above the plain. After 1900 there was a dramatic drop-off in the number of sites and purely industrial zones, suggesting that the settlement complex was collapsing with the disappearance of the river system (Mughal 1997). The Vedic hymns preserve several references to the existence and subsequent disappearance of the Sarasvati River, corroborating a theory of radical transformation in this ecosystem by about 1300. The Cholistan surveys reveal, therefore, a complete sequence: the rise of village farming communities; the elaboration of more complex settlement hierarchies; and occupational specialization leading to urban growth and subsequent decline.

Mohenjo-daro, perhaps the most important archaeological site in South Asia, excavated repeatedly since the 1920s (Marshall 1931), provides a detailed view of a primate city during the mature Harappan phase, including monumental constructions within a ‘high’ town or ‘citadel’ to the west, and habitation areas in a separate ‘low’ town of greater extent to the east. The northeastern portion of the citadel mound rises 13 meters above the plain and is the location of a Buddhist monastery dating from the early-first millennium ce that was constructed on the more ancient tell. Earlier British scholarship, never far from a military interpretive framework, described massive brickwork visible on the edges of the citadel as the remains of fortification walls (Wheeler 1968: 29–31, 40, 72–7). Hundreds of soundings on the mound have indicated, however, that its height is not part of a fortification scheme, nor is it simply the result of accumulated debris, but is a planned feature; before occupation occurred, a mobilized workforce had constructed massive retaining walls for a giant foundation that raised the bases of buildings 5 meters above a plain flooded regularly by the nearby Indus. The citadel mound has yielded the most impressive architectural remains – all constructed of mud or burnt bricks – found in any mature phase settlement. These include the Great Bath, perhaps the most photographed of all Harappan monuments: a watertight pool measuring 12 meters north-south and 7 meters east-west, capable of retaining 140 cubic meters of water. Water came from a well in a room on the east and outflow went through a drain consisting of a 1.8-meter-high drain roofed with a corbelled vault. The water was accessible by a stairway on the north side of the bath. Brick colonnades that probably supported a wooden superstructure, including screens or window frames, surrounded the bath. A public street enclosed the entire complex. The ‘granary’ to its west consisted of a foundation measuring 27 meters north to south and 50 meters east to west divided into 27 brick plinths, in nine rows north to south and three rows east to west separated by passageways, that once supported wooden pillars or beams. An ‘assembly hall’ or market in the southern part of the citadel mound featured 20 brick foundations arranged in four rows of five each. More public buildings seem to lie under the Buddhist monastery.

On the eastern mound or ‘low’ town, which also may have rested in part on a massive artificial foundation (Dales 1965: 148; Jansen 1978), the most extensive horizontal excavations of any Harappan site have revealed the plans of contiguous habitation blocks. Several boulevards running roughly north-south (including a wide thoroughfare named ‘First Street’ by the excavators) provided a means of walking directly through the entire settlement. Smaller, parallel lanes ran north-south for shorter distances, intersected by other smaller lanes running east-west – a generally cardinal orientation. Obvious differences in house sizes and layouts betoken distinct gradations in class or status. In the northeastern habitation block a large, coherent complex of rooms demonstrates an unusual sturdiness of construction, perhaps evidence of a major public building, while another co...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1 The ancient heritage

- 2 The sacred city and the fort

- 3 Emporiums, empire, and the early colonial presence

- 4 Space, economy and public culture in the colonial city

- 5 Languages of space in the contemporary city

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The City in South Asia by James Heitzman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.