![]()

Chapter 1

Labour Force Participation

Learning Outcomes

At the end of this chapter, readers should have an understanding that:

- Occupational choice is influenced by family background, education and relative earnings;

- There is a difference between private and social rates of return;

- Labour force participation (or activity rates), part-time working and self-employment vary considerably across countries, as well as by gender and age;

- The discouraged worker and additional worker hypotheses operate in different ways over the business cycle;

- There are explanations for why participation rates of women should have risen, while at the same time those of men were falling;

- The choice of voluntary or mandatory retirement can be explained in economic terms.

Introduction

Individuals spend a considerable part of their lives in gainful employment, so that the decision when to work, how much to work and in which occupations to specialise are among the most important decisions in an individual’s life. The first decision is whether to leave school as soon as possible after the end of compulsory schooling or to delay entry in order to acquire additional qualifications. This investment incurs extra costs as well as the opportunity cost of foregone earnings. To some extent, the additional investment may lock the individual into a limited number of occupational groups, so that the provision of information on rates of return and the nature of employment in particular occupations becomes crucial and may require considerable occupational guidance. Some individuals may be influenced by family and friends, though little detailed information is available on this. Outcomes may also be determined by the relative size of the cohort entering the labour market and the degree of tightness or slackness existing in the labour market when entry is made.

On entering the labour market, the individual has to choose an employer or perhaps become self-employed, though for many the latter follows a period of employment in which specific knowledge is gained about the nature of particular activities. The intensity of work may vary through the use of overtime, whether paid or unpaid, or by part-time work rather than full-time work. A small number of individuals may hold multiple jobs. For married women, in particular, there may be a number of episodes of entry to and exit from the labour market in order to produce and raise children, though parental care arrangements may enable men also to participate in some of these activities. Labour supply choices may, therefore, be family rather than individually based.

When to leave the labour market through retirement is another key decision and may be determined, in part, by the health and life expectancy of the worker, as well as by economic variables such as expected income in retirement. In part, retirement may be an employer decision based on the productivity and costs of employing older workers. Retirement may be compulsory or voluntary. As populations age, this may also impose burdens on the State, which may lead to the extension of the working life through increases in the retirement age.

The aim of this chapter is to examine each of these three questions – entry into the labour market, intensity of participation within it and exit from it as sequential decisions. On the first question, we focus on rates of return to education and the impact of family background and inter-generational transmission mechanisms, which may imply that some siblings follow parental occupations. Key aspects of the second question include the role of gender and ethnicity in determining occupational choices, the nature of the employment contract, and additional and discouraged worker effects over the cycle. On the third question, we focus on the problems of an ageing workforce and the determinants of optimal retirement decisions. We return to some of these issues in Chapters 2, 3 and 11.

1.1 Entry into the Labour Market – Education and Occupational Choice

For most workers, prospects in the labour market are already fairly well determined by the time initial entry into that market is made. Though it is fair to say that the occupational hierarchy is not entirely rigid as far as individuals are concerned, with a fair degree of movement in both upward and downward directions, nonetheless, the best predictor of the occupational position of a man aged 60 is his occupational position when he first enters the labour force (see Nickell 1982). In this respect, the key decision is how much to invest in human capital and what form this investment should take.

We would expect entry into particular occupations to be influenced by relative earnings, especially where information on the nature of employment is limited. There is abundant evidence on returns to education for particular groups, occupations and countries. Psacharopoulos (1985), for example, surveys studies relating to no fewer than 61 countries at different points in time. These point to a declining rate of return over time by country controlling both for level of education and per capita income. Thus, the returns for each level of education are highest in African and lowest in the more advanced industrial countries. This means that there is a danger that new entrants may overestimate the returns available to them if they simply assume the future will replicate the past.

We must, however, distinguish between private and social rates of return. The former can be defined as the added value of the gains due to education as a percentage of the costs to the individual of acquiring that level of education, made up of foregone earnings and the individual’s contribution to tuition and maintenance costs. The social rate of return takes into account not only the private costs to the individual, but also that share of costs borne by the rest of society through taxation, which is designed to ensure that more individuals are able to participate. This takes into account external benefits of education such as improved health, reduced crime and a higher rate of economic growth. Generally, private returns exceed social, because of the presence of state subsidies and the fact that it is difficult to include measures accounting for all the social benefits. We cannot necessarily conclude, therefore, that education is necessarily more beneficial to the individual than to society as a whole.1

Despite tendencies to declining rates of return, ceteris paribus, average returns in general have been fairly stable over time. This is explained by the fact that the growth in demand for educated manpower has kept pace with a substantial increase in supply both for developing and developed countries.

A detailed analysis of both private and social rates of return to education at the upper-secondary school and tertiary levels in various OECD countries has been carried out by Blöndal et al. (2002). They note that net benefits are strongly influenced by policy-related factors such as study length, tuition-fee subsidies and student support grants, so there is little reason to expect internal rates of return to be similar across countries given differences in policies in relation to such issues. Thus, foregone earnings will be influenced by course duration, which is much longer in some countries than others. Private tuition costs tend to be low in most European countries because of public subsidies. Similarly, financial support to students in the form of grants and favourable loan support is more generous in some countries than it is in others.

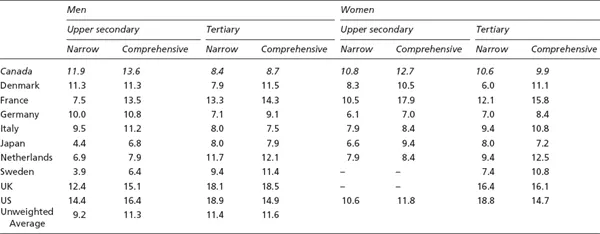

The net gains to individuals, i.e. the comprehensive internal rate of return summarised in Table 1.1 for ten OECD countries for post-compulsory education ranges between 9 and 19 per cent, with the UK and US having higher rates than elsewhere. In some cases, adjusting for taxes, unemployment risk, tuition fees and student support increases the internal rate of return because public benefits outweigh taxes, but in the UK, for instance, the difference between the narrow and comprehensive rates is much smaller than in some other countries.

Table 1.1Private internal rates of return to education in the OECD, 1999–2000(%)

Source: Adapted from Blöndal et al. (2002).

Notes: Narrow rate is based on pre-tax earnings and the length of studies

Comprehensive rate adjusts for the impact of taxes, unemployment rate, tuition fees and public student support where relevant.

For the UK data on earnings of women up to age 30 with lower-secondary education were not available. For Sweden earnings differentials for women between upper and lower secondary levels are not large enough to allow a positive rate of return to be made.

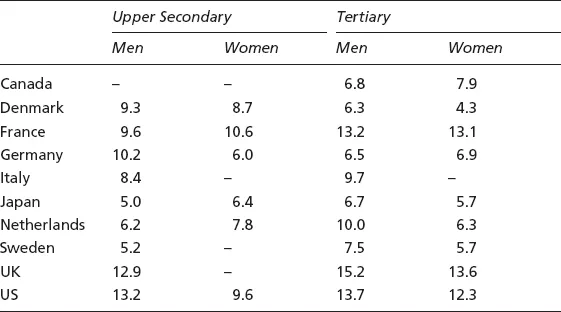

Because of the difficulties in estimating comprehensive social rates of return, Blöndal et al. limit themselves to the narrow definition which does not incorporate externalities or non-economic benefits (such as effects on crime and health) and assume that any wage gains from education represent associated productivity gains (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2Narrow estimates of social rates of return to education in the OECD, 1999–2000(%)

Source: Adapted from Blöndal et al. (2002).

Note: – Reliable data lacking.

Reflecting the fact that social costs exceed private costs of education, because of educational subsidies, social internal rates of return are generally much lower than private ones. Nevertheless, social rates of return are typically well above 5 per cent measured in real terms for both upper-secondary an...