eBook - ePub

Artistic and Cultural Exchanges between Europe and Asia, 1400-1900

Rethinking Markets, Workshops and Collections

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Artistic and Cultural Exchanges between Europe and Asia, 1400-1900

Rethinking Markets, Workshops and Collections

About this book

The European expansion to Asia was driven by the desire for spices and Asian luxury products. Its results, however, exceeded the mere exchange of commodities and precious metals. The meeting of Asia and Europe signaled not only the beginnings of a global market but also a change in taste and lifestyle that influences our lives even today. Manifold kinds of cultural transfers evolved within a market framework that was not just confined to intercontinental and intra-Asiatic trade. In Europe and Asia markets for specific cultural products emerged and the transfers of objects affected domestic arts and craft production. Traditionally, relations between Europe and Asia have been studied in a hegemonic perspective, with Europe as the dominant political and economic centre. Even with respect to cultural exchange, the model of diffusion regarded Europe as the centre, and Asia the recipient, whereby Asian objects in Europe became exotica in the Kunst- und Wunderkammern. Conceptions of Europe and Asia as two monolithic regions emerged in this context. However, with the current process of globalization these constructions and the underlying models of cultural exchange have come under scrutiny. For this reason, the book focuses on cultural exchange between different European and Asian civilizations, whereby the reciprocal complexities of cultural transfers are at the centre of observation. By investigating art markets, workshops and collections in Europe and Asia the contributors exemplify the varieties of cultural exchange. The book examines the changing roles of Asian objects in European material culture and collections and puts a special emphasis on the reception of European visual arts in colonial settlements in Asia as well as in different Asian societies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Artistic and Cultural Exchanges between Europe and Asia, 1400-1900 by Michael North in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Asian Objects and Western European Court Culture in the Middle Ages

Introduction

This collection focuses on the contacts between Asia and Europe after the discovery of the Cape-route by Vasco da Gama in 1498. From then on, the import of Indian and Chinese commodities to Europe became an increasingly easier business than it was in the centuries before.1 The aim of the present article is to show that despite the difficulties of importation, Asian objects played an important part in European court culture already in the Middle Ages.

It should be pointed out right at the beginning that spices are not considered here. They certainly had a representative function in the consumption habits and dinner customs of ecclesiastical and secular rulers, but most spices, especially pepper, had become so widespread in the later Middle Ages that they were common in urban households as well.2

Silk is also left aside, although silk-cloth has already been imported into Europe from China or Central Asia since the Early Middle Ages.3 Archaeological excavations have unearthed bits of silk-cloth and even medieval silk gowns can be found all over Europe, but the provenance of the silk is difficult to establish; it may be of Chinese origin, but in some cases Southern Europe appears also to be a likely candidate.4 In addition to that there is a methodical reason for not including silk into this study: Silk is generally not mentioned in medieval inventories.

When analysing the distribution of Asian luxury-goods, only objects which have physically survived, and those mentioned in written sources can be taken into account. The study of material court culture in the medieval West has primarily been undertaken by art historians, whose work could, however, only be based on the few surviving physical witnesses. Ninety-nine per cent of golden and silver tableware alone has been lost, while pieces decorated with gems and pearls were re-worked or re-modelled according to the fashion of their day, so that they do not survive in their original state.5 Inventories of Medieval treasures are only a reminiscent of the wealth of European courts, where especially exotic objects from India were held in great esteem.6

Here, the focus lies on gems, coconuts, and nautilus shells, all of which exclusively imported from India, as well as porcelain, which, though originating in China, was associated with India by being termed ‘earth of India’.7 While coconuts, nautilus shells, and gems arrived in Europe as natural products, porcelain was the result of craftsmanship. Still, all four of these objects had one aspect in common, namely their rarity,8 which made them extremely valuable.9 Even though it took some decades after the discovery of the Cape-route before these four objects were imported in greater numbers, the present survey ends at around 1500, i.e. before the notable increase in commerce due to Vasco da Gama’s arrival in India.

Fascination of Gems

The first objects to be discussed here are gems. Because of their colour, brilliance, and reflection of light, gems have fascinated people continuously from the Middle Ages to the present day.10 The most popular gems of the Middle Ages were diamonds, rubies, balas rubies, sapphires, and emeralds.11 Even though balas rubies were, in fact, imported from Persia and emeralds from Egypt,12 India was in all cases regarded as their place of origin, primarily because balas rubies and emeralds arrived in Western Europe via the same trade route as did Indian gems. Diamonds are only rarely attested in the late medieval inventories of European rulers. The gentle lustre of these gems, achieved by careful polishing, was apparently not as appealing to the medieval eye as the open brilliance of cut diamonds. Accordingly, the popularity of diamonds increased considerably from 1400 onwards, when the cutting of diamonds had been developed in Paris; the technique applied, however, led to a loss of c. 50 per cent of the original gem.13

Besides gems (in the direct sense of the word), pearls should also be noted here, since they were often combined with gems as decoration of certain objects. In the Middle Ages, the two main pearl-fishing resorts were located between the Indian main land and Ceylon on the one hand, in the Persian golf on the other.14 While smaller pearls were used as pieces of embroidery on precious fabrics,15 bigger pearls could be found beside rubies, sapphires, and diamonds on exquisite pieces of jewellery.

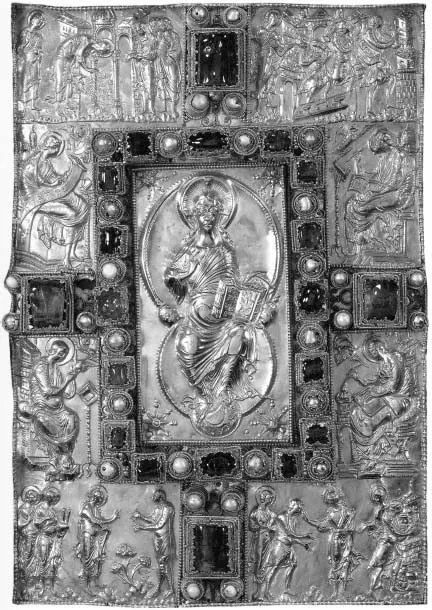

In the Middle Ages, gems were, however, not only valued for their beauty, but a certain Christian symbolism was also attached to them. The description of Jerusalem in the Apocalypse is of primary importance in that respect, since there the 12 corner stones of this city consisted of different gems, while the city wall was made of jasper, every single one of the 12 city gates was of pearl.16 Many Biblical commentaries deal in detail with the gems referred to in the Apocalypse, so that through this medium knowledge about these gems became more widespread.17 Additionally, gems also fulfilled medical functions, either by use of their powder after being ground or as objects associated with a certain healing or magical character (Figure 1.1).18

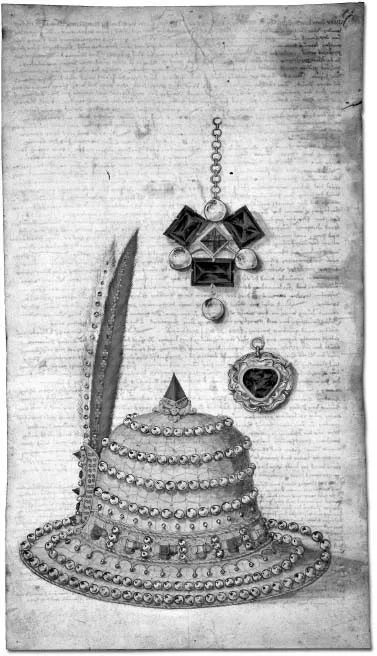

The symbolical importance of gems in the Christian milieu led to their use as decoration of crucifixes, chalices, reliquaries and Gospel books already in the early Middle Ages.19 The Christian ideology of god-given kingship and the exclusiveness of kingship were, then, symbolized by gems on medieval crowns.20 Accordingly, the crown of the Holy Roman Emperor was decorated by 144 gems,21 while the shining beauty of the crown of Blanche of England, based on 33 diamonds, 33 rubies, 11 sapphires, and 132 pearls, has lost nothing of its fascination to the present day (Figure 1.2).22

Fig. 1.1 Front cover of the Codex aureus of St Emmeram in Ratisbon, saec. IX2 Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14000.

Fig. 1.2 Crown of an English queen (the so-called Bohemian or Palantine Crown, c. 1370–80). Residenz Museum, Munich.

Besides royal insignia, golden tableware decorated with gems used for personal purposes are frequently recorded in the inventories of Medieval rulers. Evidently, the increase in income of European rulers, due to population growth and a more efficient tax system, apparent from the fourteenth century onwards, was paralleled by a notable increase of luxury objects from India.23 When Pierre Gaveston was caught in flight, he carried a considerable part of the crown-treasure of the English king, including ‘a gold cup, enamelled with jewels, which Queen Eleanor gave to the present king with her blessing’, as well as numerous golden rings with rubies, sapphires, and diamonds; one of these rubies had the fitting name ‘la cerise’.24 The English King Edward IV possessed, in 1468, a golden container for salt of eight kilograms in weight and decorated by 249 pearls, 70 rubies, 25 diamonds, and nine sapphires,25 while the Duke of Bedford used a nef (a miniature ship) displaying 75 rubies, 19 oversized, and 400 normal sized pearls as decoration for his table.26 The inventory of Charles the Bold of 1467 listed numerous liturgical objects and tableware, as well as other pieces of jewellery and garments decorated with gems, which were supposed to display the wealth and pre-eminence of the Burgundian court;27 e.g., his hat (Figure 1.3), which served as a substitute for a crown, showed 14 sapphires, 35 balas rubies, and 63 pearls (of three carats each)28 while its feather contained three enormous diamonds, nine big balas rubies, three great pearls (of eight carats each), as well as 46 additional pearls of a lesser size;29 even one of his hunting bags had nine diamonds, five pearls, and four rubies.30

Pieces of jewellery and tableware decorated with gems and pearls were, however, not only used for private purposes, but they also were popular gifts among Western kings and princes. On New Year’s Eve of 1397, Charles VI of France received as a gift from Louis of Orléans a chalice decorated with four over-sized and 41 normal-seized balas rubies, nine sapphires and 141 pearls.31 Gems were, particularly on New Year’s Eve, also presented to bigger groups, since the differences in size and value made it possible to accommodate the differences in status and rank, while, at the same time, no single person of the group had to be neglected;32 e.g., the court ladies of the Queen of France received 46 diamonds in total, of which five were worth 200 pounds each, another 12, on the other hand, only 10 pounds, the latter being given to persons of lower rank.33

Fig. 1.3 Single vellum leaf of c. 1545 displaying three pieces from the Burgundian booty of Charles the Bold: the Golden Hat, the three Brothers, and the White Rose. Historisches Museum, Basel, C 6565, Inv. Nr. 2007.511.

Consequently, rulers had a considerable interest in accumulating a great number of gems, particularly those that were either extremely rare or of an exceptional size. At the battle of Grandson, Charles the Bold lost not only a diamond of 139 carats decorated with two additional pearls, which had an estimated value of 20,000 fl and which was subsequently sold to Ludovico Moro of Milan and later to Pope Julius II, but also the so-called Balle de Flandre, a diamond of 106 carats, which since formed part of the French crown jewels before it was bought, in 1875, by the Maharajah of Patiala, who restored it to its place of origin with this act.34

The constant struggle for the acquisition in great numbers of rare gems by European courts is well-illustrated by a woodcut of the treasury of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian, which shows numerous necklaces, necklets, and strings of pearls, accompanied by the following text:

The biggest treasure belongs to him alone / containing silver, gold, and precious stone / with shining pearls in such amount / unknown to any other count / of this he gives plenty and more / for God’s service, glory and honor.35

This trend set by kingly and princely courts was also taken up at courts of lower rank, which tried to acquire gem...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction - Artistic and Cultural Exchanges between Europe and Asia, 1400-1900: Rethinking Markets, Workshops and Collections

- 1 Asian Objects and Western European Court Culture in the Middle Ages

- 2 The Euro-Asian Trade in Bezoar Stones (approx. 1500 to 1700)

- 3 Asia as a Fantasy of France in the Nineteenth Century

- 4 Material Culture, Knowledge, and European Society in Colonial India around 1800: Danish Tranquebar

- 5 Changing Cultural Contents: The Incorporation of Mughal Architectural Elements in European Memorials in India in the Seventeenth Century

- 6 Production and Reception of Art through European Company Channels in Asia

- 8 Interpreting Cultural Transfer and the Consequences of Markets and Exchange: Reconsidering

- 9 An Assimilation between Two Different Cultures: Japan and the West during the Edo Period

- Index