- 262 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Japan and the High Treason Incident

About this book

The 'High Treason Incident' rocked Japanese society between 1910 and 1911, when police discovered that a group of anarchists and socialists were plotting to assassinate the Emperor Meiji. Following a trial held in camera, twelve of the so-called conspirators were hanged, but while the executions officially brought an end to the incident, they were only the initial outcome as the state became increasingly paranoid about national ideological cohesion. In response it deployed an array of new technologies of integration and surveillance, and the subsequent repression affected not only political movements, but the whole cultural sphere.

This book shows the far reaching impact of the high treason incident for Japanese politics and society, and the subsequent course of Japanese history. Taking an interdisciplinary and global approach, it demonstrates how the incident transformed modern Japan in numerous and unexpected ways, and sheds light on the response of authoritarian states to radical democratic opposition movements elsewhere. The contributors examine the effects of the incident on Japanese history, literature, politics and society, as well as its points of intersection with broader questions of anarchism, colonialism, gender and governmentality, to underline its historical and contemporary significance.

With chapters by leading Western and Japanese scholars, and drawing on newly available primary sources, this book is a timely and relevant study that will be of great interest to students and scholars working in the fields of Japanese history, Japanese politics, Japanese studies, as well as those interested in the history of social movements.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

Assessing the significance of the high treason incident

Now and then in Japan

1 The centennial of the high treason incident

The high treason incident

How has it come about that I committed this grave crime? Today, my trial is closed to outside observers and I have even less liberty than previously to speak about these events. Perhaps in a hundred years' time someone will speak out about them on my behalf.(1911)

Introducing new documents relating to Kōtoku Shūsui and Kanno Suga

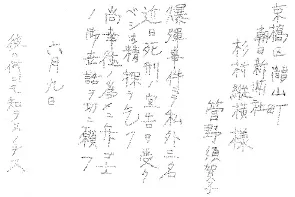

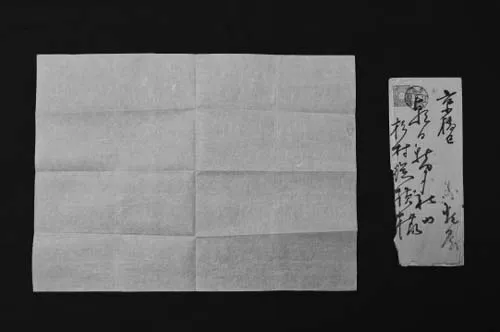

A letter from Kanno Suga to Sugimura Sojinkan

[To] Mr Sugimura Jūō,The Asahi Newspaper Co.,Takiyama village, Kyōbashi ward[From] Kanno SugakoIn the bomb incident, three others and I will probably soon be sentenced todeath. I implore you to investigate thoroughly. In addition, I beseech you tofind a lawyer to represent Kōtoku.The ninth of JuneHe knows nothing.

A letter from Kōtoku Shūsui to Oka Shigeki

Dear Mr Oka Shigeki,I am sorry for my lack of correspondence. I hope this letter reaches you ingood health and prosperity.With this letter I must report to you some lamentable news. This is nothing less than the dissolution of the Heiminsha. The dissolution is a result of, on the one hand, being unable to withstand government persecution, and on the other, having exhausted our fnancial and physical capabilities.After being released from prison, I was sorry to find that Mr Kosen5 was practically alone in managing the affairs of the Heiminsha, which was suffering from the government's insidious and moreover ruthless persecution. All over the country, police were hindering the sale of Heiminsha journals and books, making it impossible to develop a fourishing business, and therefore fnancially, we were short every month and could not make ends meet. After much deliberation, we fnally decided to reduce the scale of our operation, and publish only the journal, Chokugen (Straight Talk). I thought that we could somehow get through like this, even if we only barely got by. However, due to the recent great disturbances throughout the whole of Tokyo, publication of most newspapers has been banned.6 Publication of Chokugen was also prohibited this time. Shortly afterwards, most newspapers were allowed to resume publishing, but Chokugen, along with the Niroku shinpō (24 Hours Update) newspaper, both of which are especially detested by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department, did not receive such permission. Chokugen received the order to cease publication on the 10th of last month. Over a month has passed and we still have not been granted permission to resume. It appears that the government is taking these illegal measures to completely eliminate Chokugen and the Heiminsha. Faced with these conditions, and given our destitute state, we no longer have the power to keep our association going. We have fnally accepted the inevitable and on the 26th of last month the very day that Nishikawa Kōjirō was released from prison, we swallowed our resentment and wound up the association for the time being.I do not know when we will be allowed to resume publication of Chokugen, and although I feel that we could perhaps continue once martial law is lifted, it seems impossible to publicly enjoy freedom of speech under this lawless government. Actually, on the 27th, we were slapped with a fne of over 200 yen in the Court of Appeals for publishing the Communist Manifesto.The others are busy doing their best to put their lives in order given the above circumstances; Sakai [Toshihiko] has resolved to publish family magazines and ordinary publications for a meagre subsistence, and I am currently convalescing and preparing for my trip to the United States. After being released from prison, I tried to resume my activities. However, because the external circumstances are as I have described above and I am viciously in the bad graces of the government, taking part in the movement is extremely difficult. Moreover, my health at present does not permit it, so I have decided to travel to San Francisco, where I shall take it easy for six months or a year, while forging ties with comrades in your area. There is not even the slightest freedom of speech or association in Japan, so I think that political freedom in the United States will be much more conducive to discussions. However, as this will be my frst time out of the country, I shall probably be troubled by many unfamiliar things, so I would like to ask for your guidance in all matters.As you know, I do not have the fnances to support my family, so I plan to entrust my mother to relatives in my hometown, my wife to relatives in Tokyo, and travel to San Francisco with one of my nephews. He is a boy of sixteen and still a middle school student, and when I leave there will be no one to care for him, so I plan to bring him along to San Francisco with me and have him find work so that he can support himself. He is in robust health, so all he needs is a job, and therefore I would like to ask for your assistance.Although the Heiminsha has been dissolved, the world is moving in the direction of socialism. All around the world, socialist ideas are quietly four-ishing, showing no trace of decline, so there is no need for excessive concern. I am certain we will have opportunities in the not too distant future, but until then I want somehow to continue publishing Chokugen so as to remain in contact with our comrades. We are currently working hard on this matter, and I hope we can do something about it before I depart for San Francisco. For now, I plan on staying in the United States for more than six ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Routledge contemporary Japan series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Note on names

- Map of principal places related to the high treason incident

- Introduction

- Part I Assessing the significance of the high treason incident: now and then in Japan

- Part II Colonialism and the high treason incident

- Part III Anarchism and the high treason incident

- Part IV Gender and the high treason incident

- Part V Literature and the high treason incident

- Part VI Biography and ideology in the high treason incident and beyond

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index