![]()

1 Tokugawa Japan

From premodern to early modern

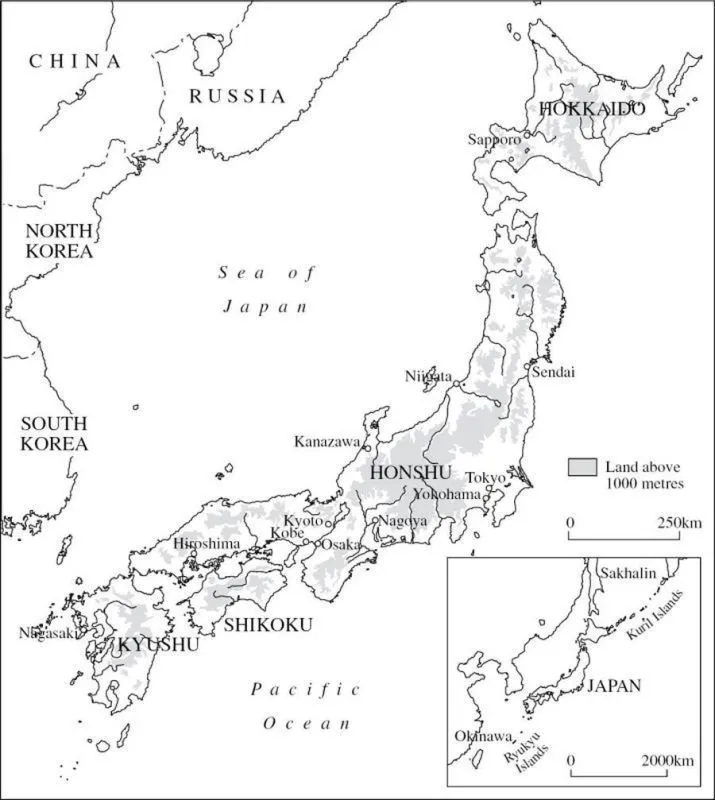

Map 1.1 Modern Japan

‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there’.1 This famous line from a post-Second World War novel about Victorian England might also seem to apply to our view of the Tokugawa world from the twenty-first century. Tokugawa political institutions and modes of behaviour do not fit our modern understandings and terminology. Indeed, fifty years ago Western histories of modern Japan often started with 1853, the year that Commodore Perry ‘opened’ Japan to contact with the West, or with 1868, the year of the Meiji Restoration and the beginning of the government that consciously started Japan’s modernization process. Yet today, no history of modern Japan would ignore the Tokugawa conditions that shaped the modernization process.

In addition, the Tokugawa past remains alive in the present, not just in Japan, but also other parts of the world. ‘Premodern’ or ‘traditional’ figures from the period – samurai, ninja, rōnin, geisha – now appear in mainstream Western popular culture. They appear in advertisements, movies (e.g. The Wolverine) and television (Revenge), utilized in comic ways as well as deployed with mixed attitudes toward the behaviour and values they are seen to embody. Japan specialists may criticize the stereotyping of Japanese behaviour and values depicted in the media, but the frequency of their representation assumes widespread, if not accurate, familiarity with Japan’s past in the modern world.

Moreover, the fact that historians now refer to Tokugawa Japan as ‘early modern’ rather than ‘premodern’ suggests that the Tokugawa world might not be entirely foreign either. The two-and-a-half-century-long ‘Great Peace’ and remarkable stability of the official sociopolitical order masks significant changes which make comprehensible, though not inevitable, the great transformations of the late nineteenth century.

The Tokugawa order

Because the impetus for change derived from a growing gap between the official ideal of the socioeconomic and political order, on the one hand, and the reality, on the other, we need to begin with a simple (and simplified) outline of the Tokugawa social and political structure and the assumptions and objectives underlying it.

Perhaps the most fundamental attribute of the Tokugawa governing structure was its military character, the result of over a century and a half of civil war since the mid-fifteenth century. Japan had been politically fragmented into 250 and sometimes more territories, dominated by military lords who constantly fought one another to expand their domains, displaying many similarities with the feudalism of contemporary Western Europe. Oda Nobunaga, the first of the ‘Three Heroes’ or ‘Great Unifiers’, began the process of military unification in the 1560s, and Toyotomi Hideyoshi completed it in 1591. Hideyoshi carried out administrative measures, notably a nationwide ‘sword hunt’ to disarm the peasants, and a land survey which separated samurai from peasants and demonstrated recognition by the other feudal lords of his pre-eminence as sole proprietary lord in the country. These policies contributed greatly to a fundamental revolution in Japanese political and social institutions. Hideyoshi also launched two invasions of Korea as part of an ambitious attempt to create a Japanese empire extending through China.

Besides failing to conquer Korea, however, Hideyoshi was not successful in passing on his power and authority to his 5-year-old son after his death in 1598. Out of the intrigues and alliances, two large coalitions of feudal lords, or daimyō, emerged, bringing their armies of 80,000 each to confront one another at the battle of Sekigahara in 1600. After his victory, Tokugawa Ieyasu and his heirs in the first half of the seventeenth century constructed a system that remained stable enough to last for more than two and a half centuries – that is, until the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Ieyasu initially strived to legitimize his power with the help of imperial authority by becoming the emperor’s highest military official – ‘barbarian-quelling generalissimo’ or shogun.

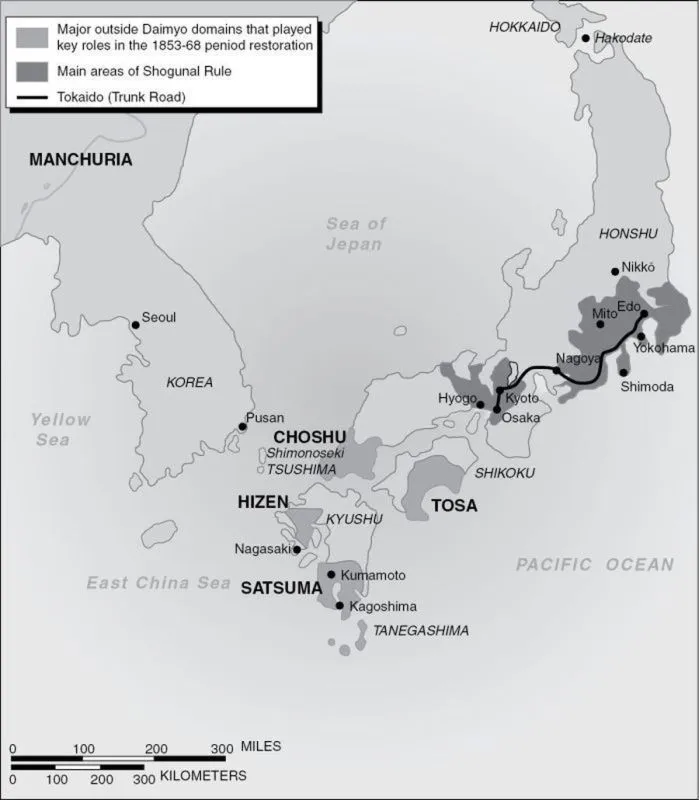

In order to end the bloody civil wars as well as ensure lasting Tokugawa rule, Ieyasu and his successors had to create a political and social structure that would maintain control over the other daimyō. They forced the daimyō to swear loyalty and service to the Tokugawa shogun in a feudal manner and in return reinvested them with domains, now defined in terms of income calculated in measures of rice as well as territories. This included even former enemies at Sekigahara, the so-called ‘outside’ or tozama daimyō, who remained some of the wealthiest individuals even though they held domains far from the political and economic centre of the country.

On a practical level the early Tokugawa shoguns continued or extended many methods that daimyō had previously been utilizing to control their samurai retainers, such as rotation and confiscation of fiefs; strategic placement of daimyō allies; marriages and adoptions to cement political links; and bestowal of honours and material rewards for meritorious service and loyalty. Perhaps the most important of these in its long-term effects was the system of alternate attendance (sankin kōtai). This represented the culmination and institutionalization of the practice of hostage-taking by feudal lords to ensure the loyalty of samurai vassals in a time when treason and betrayal ran rife. The Tokugawa system required daimyō to be in attendance at shogunal headquarters in Edo (present-day Tokyo) so that the shogunate could keep them under close supervision. In alternate periods, usually every other year, when they were allowed to return to their domains, the shogunate forced them to leave their families in Edo as hostages. The system was also designed to drain the financial resources of the daimyō, since it required not simply minimal maintenance of two residences, but residences and personnel of a number and level of luxury commensurate with their rank.

Map 1.2 Tokugawa Japan

In addition, the shogunate instituted restrictions on foreign trade in order to deprive daimyō of lucrative sources of revenue and to reduce political threats associated with Spanish and Portuguese missionaries. The shogunate also employed diplomatic relations to enhance the status of the shogun. These were the motives behind the so-called closing of the country in the 1630s, which involved the suppression of Christianity and the expulsion of all Europeans apart from the Protestant Dutch, after they demonstrated that their interests were confined to trade and not religious proselytizing or politics. The shogunate confined the Dutch to a man-made island in Nagasaki harbour and maintained a monopoly control over foreign trade and its profits through that port. Notable exceptions, however, were permission for Tsushima’s trade with Korea and Satsuma’s with the Ryukyu Islands in the south. Korean embassies received by the shogun helped to legitimize the Tokugawa hegemony over the daimyō, since the shogunate treated them as tribute missions in a Japan-centred world order, even though from the Korean perspective Korea regarded the Japanese ruler as an equal rather than a superior. For the same reason, the shogunate refused to engage in official relations with China because this would have meant acknowledgement of a subordinate position in the Chinese world order and loss of status in the eyes of the daimyō, but it carried out a profitable trade with private Chinese merchants through Nagasaki.

In addition, in the early eighteenth century Shogun Yoshimune lifted the ban on European books in non-political and non-religious fields. This allowed the beginning of Dutch and later more broadly Western studies, which were attractive to some Japanese for their practical application. For example, doctors even in rural districts at the beginning of the nineteenth century turned to Western medicine to treat the effects of famine and to prevent epidemics. In art, popular landscape printmakers Hiroshige and Hokusai, as well as Dutch Studies artists, adopted Western techniques of perspective in their compositions for their realism. Tokugawa Japan thus had a door open to the West while maintaining active relations with other East Asian countries, so that the image of a closed country should not be overdrawn.

The various practical measures taken to ensure Tokugawa hegemony were necessary since the shogunate or bakufu governed and taxed areas only under direct Tokugawa control (amounting to about a quarter of Japan) and possessed authority over the daimyō only in matters such as foreign policy that affected the country as a whole, or when disputes crossed domain borders. It delegated administration of the rest of the country to the daimyō, who governed and obtained income from their domains, known as han, more or less as they pleased, so long as they did not display disloyalty to the shogunate. Consequently, although the Tokugawa shogunate was the most centralized government Japan had had so far in its history, it did not exercise complete centralized authority. Hence the term bakuhan in Japanese for the system representing a balance of power between the bakufu and han.

From a broader historical perspective, the consolidation of this balance between central authority and local autonomy differed from what was happening in Western Europe, where absolute monarchies were in the process of being established. In the past, the divergence from European developments led historians to view the Tokugawa system negatively. The reference by some historians to ‘refeudalization’ during the early 1600s suggests their view of the Tokugawa political order as a kind of arrested political development that could be blamed for Japan subsequently missing out on the scientific and industrial revolutions, falling behind the West and therefore having to ‘catch up’ in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Focus on the limited contact with Europe reinforced this view of backwardness. Similarly, the once prevalent description of the system as ‘centralized feudalism’ highlights the difference from Western political developments. It also implies a contradictory nature, since feudalism is characterized by decentralized political authority, and hence a rather negative judgment of it. Recent historians, such as Luke Roberts, describe the relationship between the shogun and daimyō as ‘feudal’, but without the negative connotations. Roberts stresses that the performance of submission to the shogunate and its laws, even while daimyō and han officials negotiated their noncompliance in the background, helps to explain the longevity of the Tokugawa order.

When earlier historians’ focus remained on Tokugawa feudalism, the establishment by the Tokugawas of a hierarchical, hereditary status system drew attention to the samurai as the most important actors in the history of the period, as well as reinforcing the overall image of stagnation and oppression. This latter tendency was especially strong among Marxist Japanese scholars, for in Marxian use ‘feudal’ refers to a society where farmers are bound to the land and denied political power, paying high taxes to a ruling class of military men. In post-Second World War Japanese usages, ‘feudal’ often referred to social and political traits going back to the Tokugawa period that had not yet been destroyed in the process of industrialization and modernization, such as hierarchical structures and relationships, loyalty and obedience to superiors and vertical divisions in society. The term was therefore often used in critiques of Japanese society and politics.

The important point in this discussion of debates over appropriate terms to describe the Tokugawa order is that views of the past are shaped by evaluations of the present. Consequently, in light of Japan’s dramatic economic success since the Second World War, the image of Tokugawa Japan has gradually changed. Instead of depicting Tokugawa Japan as the feudal source of the authoritarianism and repression characteristic of politics until the end of the Second World War, many historians now emphasize the economic and social changes that occurred beneath the feudal façade and laid the foundations for modern developments. Conrad Totman’s preferred term, ‘integral bureaucracy’, indicates the more positive evaluations of Japan’s past. It suggests the early modern features of the Tokugawa period by shifting attention to the important role played by merchants as well as the samurai. Merchants had arisen as a new social group during the medieval period, but became prosperous and economically powerful during the Tokugawa period. ‘Integral’ reflects a complex relationship of cooperation between merchants and samurai. However, the term does not suggest the tension and conflict that also developed between them.

The social and political tensions inherent in the Tokugawa system, as between shogun and daimyō and between samurai and merchants, were kept in check for a long time. At first they were assuaged and later they were masked by the ideological rationalization of the Tokugawa order. Neo-Confucianism from China, via Korea, developed as another method used in the process of legitimation and stabilization in the seventeenth century. Although historians such as Herman Ooms have revealed that Neo-Confucianism was not the exclusive orthodoxy once presumed, it is still fair to say that it provided a philosophical foundation not only for the political order but for the socioeconomic order as well. Rather than a religion, Neo-Confucianism constituted an ethical code linking proper behaviour in social life to proper conduct of government. Since it posited that a good government is a government ruled by ethical, cultured men and a benevolent paternalistic ruler, it could be used to help transform the samurai class into a civilian bureaucratic class in a time of peace. It further justified the social order by the assertion that if everyone performed the duties and obligations of their place in society, there would be order, harmony and stability.

In its assumption of a natural hierarchical order in society, it underpinned the status system that ranked the four main status groups – samurai, peasants, artisans and merchants – in order of their presumed usefulness to society. Those employed in what were considered ‘impure’ occupations, most associated with killing animals and burying the dead but also various police and jailhouse duties, fell below and outside the four main status groups and were known as eta (literally, ‘great filth’). Beggars, criminals, prostitutes and actors were also categorized as outcasts, in their case hinin (‘non-human’).

This outline is highly schematic, for, as David Howell has pointed out, these status categories were broad and fluid, encompassing numerous subgroups with their own internal rankings. And, as will become clearer in the discussion of economic developments, status did not necessarily correlate with wealth, standard of living or means of livelihood, even though it served as a marker of identity, community membership and an individual’s relation to political authority. A striking example is Danzaemon, who controlled about fifty outcast groups and territories in Edo and the surrounding Kantō region. Eta were generally marginalized, segregated and discriminated against in their social relations, but Danzaemon’s role in maintaining the social order was considered so important that he was permitted to carry two swords and behave like a minor daimyō. And though having to fend off periodic challenges from rivals, succeeding Danzaemons continued to exercise authority to monitor and control outcast groups until the end of the Tokugawa period.

Although they were not subjected to systematic discrimination like eta and hinin, assumptions of female inferiority and dependency relegated women to a subordinate status in society. As Kaibara Ekken’s Onna daigaku (The Great Learning for Women) of 1716 declared, ‘seven or eight out of every ten women’ suffered from the ‘five infirmities’ of indocility, discontent, jealousy, silliness and slander. Such misogynist assumptions no doubt underlay women’s lack of autonomy in either a legal or social sense. Their status was determined by that of the household head, who was normally and normatively a man. Nevertheless, as in the case of outcasts, the common view of the Tokugawa period as the nadir of women’s position in Japanese society may be overdrawn, for there were some cultural areas, such as the tea ceremony and poetry writin...