![]()

Part One: The canonical avant-garde

Origins of the moving image (1780–1880)

New movements in cultural history rarely have a single and agreed starting date, and to trace either the moment when cinema began or when it became an art is a matter of argument. The emblematic years 1895/6, when the Lumières first demonstrated their machine in Paris and London, are an endpoint as much as anything else, for behind those dates stands a long period of research and development in Europe and the USA. Nor did the Lumière brothers think they were making art. Even more arguable is the relation of cinema to the other art forms of the late nineteenth century, including realist painting and drama, as well as the modernism which is the main subject of this historical review.

Modern art and silent cinema emerged at roughly the same time, after a long period of mutual gestation. Both came at the end of a century which was fascinated by the art and science of vision. It underpins the composer Claude Debussy’s notion that ‘music is the arithmetic of sounds as optics is the geometry of light.’51 Cézanne, who surfaced from long years of self-willed obscurity to become recognised as a master of ‘post-impressionism’ in the mid-1890s, wanted to ‘develop an optics, by which I mean a logical vision’.52

Photography, which had been born from the science of optics, and is a third point of triangulation between art and cinema, had already made its impact on visual artists from the 1840s onwards.53 It left its trace on the subject-matter, the style or the method of every advanced artist of the period – including Manet, Seurat and Degas – just as it challenged and redefined the picture-making of more traditional, academic painters and sculptors. But both sides drew different lessons from the photograph. While the Impressionists and their followers were typically struck by the surprise or chance-effect of the snapshot, narrative painters focused on the illusionist realism and surface of the Daguerreotype or photogravure. Both groups were quick to use photography as a visual aid or as a means of documentation, thus adding to that extensive ‘archive’ of photo-images which now engrosses historians of the early modern period.

Photography may link artists with proto-cinema, but it is necessarily a static form of representation which slices time into fractions to achieve its effect. The paradoxes of photographic time continue to fascinate artists today, just as they stimulated such thinkers as Baudelaire, Bergson, Benjamin and Barthes, but the key and missing element – the ‘capture’ of movement – had to be added to the scientific study of optics before the diverse arts and technologies which made cinema possible were in place. Here science added a further link to the chain as it turned to ever more experimental procedures. By the mid-nineteenth century, in the influential researches of the scientist Helmholtz, for example, the traditional ‘static’ medical anatomy of the eye was joined to the more fluid and investigative study of colour and light perception which had been pioneered – along quite different lines – by Newton and Goethe, and then by technologists such as Chevreul,54 in the century between 1728 and 1839.

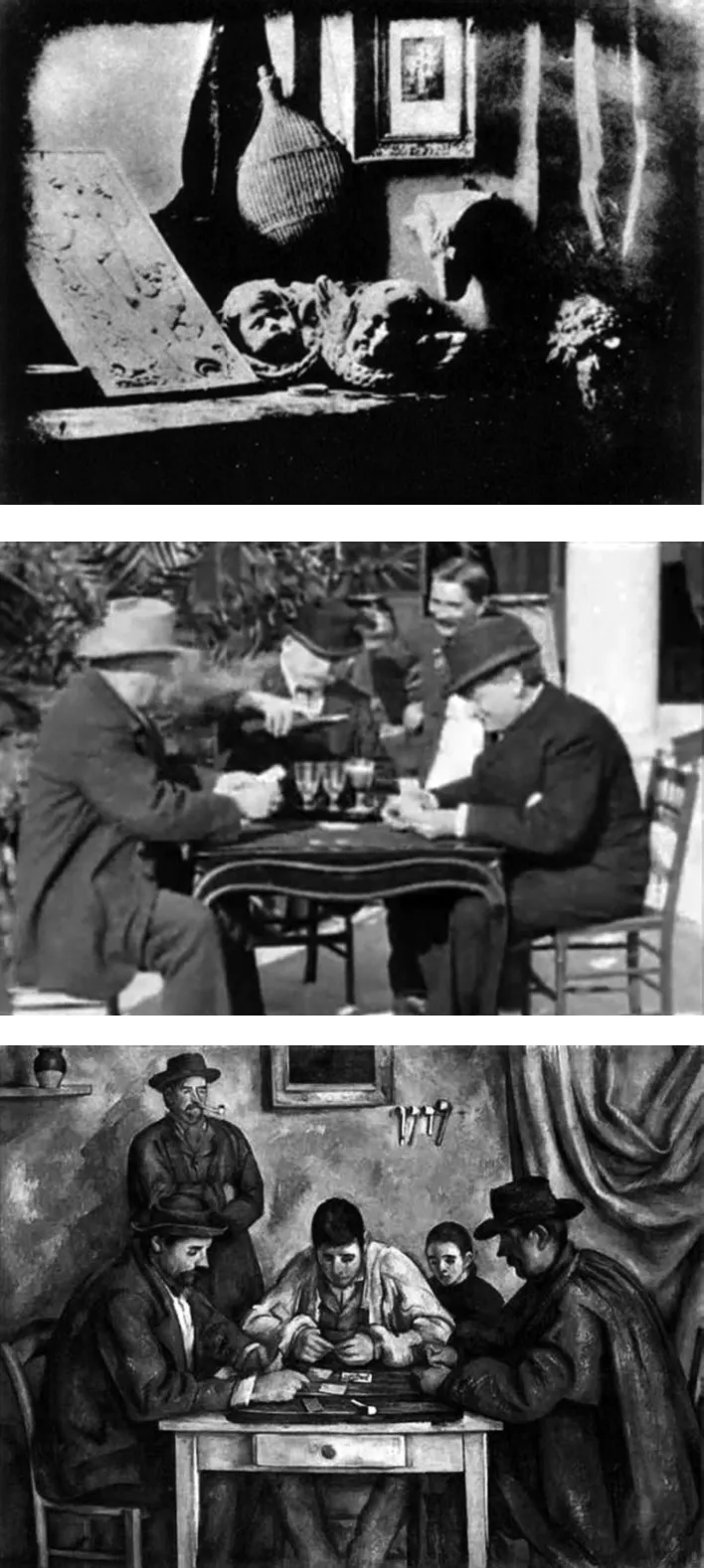

Daguerrotype (Louis-Jacques Daguerre, 1839); Card Players (Lumière, 1895); Card Players (Paul Cézanne, 1890–2)

Chevreul’s analysis of colour harmony appeared in 1839 at the same time as the famous public announcement of photography’s invention in France. The next year, 1840, the President of the Royal Academy in Britain, Sir Charles Eastlake, published his translation of Goethe’s (anti-Newtonian) Theory of Colour (1810). Soon afterwards the 70-year-old Turner painted Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) – the Morning after the Deluge, a title which plays on two senses of vision, the scientific and the sublime. Both Turner and Constable, who studied not only nature but the meteorological research of Luke Howard for his famous studies of clouds,55 were to affect two generations of French artists from Delacroix to Monet for whom painting was above all an art of light and colour. Constable’s influence on French artists was first noticed by the critic Villot in 1857. The early audiences who responded so vividly to the movement of trees and shadows in the background of the Lumières’ film Feeding Baby – almost an Impressionist subject sprung to life – were thus seeing a complex heritage pass before their eyes, just as the Lumières’ film of the Card Players, also 1895, unconsciously echoes Cézanne’s paintings on that theme.

If the first viewers of film made such unlikely connections (had they gone to both Cézanne’s Paris exhibition and the Lumière screenings in 1895, for example), they did not record them. It was not until cubism, and even then at a late stage in its development, that a context was offered in which artists might make films themselves, opening a new option for the modern movement, then also known as ‘the avant-garde’. But even early cubism was quickly seen to be ‘cinematographic’ in its concern for movement and viewpoint, and by a happy chance the French philosopher Bergson used that very phrase in 1907 to describe – not uncritically – the process of perception. A year later two young and unknown painters, Picasso and Braque, were pursuing their ‘laboratory research’ (Picasso), ‘like two mountaineers roped together’, as Braque recalled.56 They were climbing in Cézanne’s footsteps, developing his ‘passage’ or overlap between forms just as Bergson focused on ‘passage’ in time.57

Increased attention to the moving image, the cinematographic, was one crucial aspect of the European arts and sciences as they entwined towards the middle of the nineteenth century. Eighteenth-century rationalism had evolved into a broader ‘psycho-physics’, as Helmholtz called it, to produce demonstrable results from fleeting effects. Leonardo da Vinci had long ago noted such effects as a whirling firebrand which seems to leave a circular trace in the eye. Simulated movement and the persistence of vision were studied by such early modern scientists as Rouget and Faraday, typically by observing the spokes of rotating wheels. Between 1829 and 1833 Plateau in Brussels and Stampfer in Vienna had mapped the successive positions of a figure in movement around the circumference of a turning disc. These brief ‘shots’ of moving people, birds and animals were viewed through a sequence of slits and reflected in a mirror. Optical toys were the commercial result of this activity, adding to the kaleidoscope and stereoscope invented by Sir David Brewster. Popular variants such as the stroboscope, phantasmascope and zoescope culminated in Horner’s drum-mechanism Zoetrope, highly marketable from the 1860s, and Raynaud’s sophisticated Praxinoscope from 1877. A further direction of research, which ultimately passed into synaesthetic art and the abstract film, pursued the equivalence of sound and light. In this period, it goes from Goethe and Turner to Rimington’s concert of ‘colour music’, also in the emblematic year 1895.

Photography

Photography grew along with and often overlapped these developments in the art of motion. Some recent historians have questioned the tendency to treat such optical inventions as merely the stages by which ‘proto-cinema’ finally led to the real thing. Such genealogies are often traced back to the camera obscura, a closed box fitted with a lens which focused a sharp image onto a flat surface, used as a drawing aid from the Renaissance onwards. But it is also argued, following Jonathan Crary,58 that the fixed and static framing of the camera obscura is very different from more fluid and active moving-image devices like the praxinoscope, suggesting a different model of spectatorship less firmly centred on the centralised gaze. The career of a pioneer like Daguerre shows, however, that the traditional litany of names and devices making up ‘proto-cinema’ offers real insight into the period.

Niépce’s first successful experiments in photography from 1816–22 expanded after his partnership in 1829 with the more entrepreneurial Daguerre. A year after Niépce’s death in 1836 Daguerre perfected a silver and mercury method of printing which led to official recognition of the new art in 1839. Fox Talbot’s invention of the negative in 1835, inspired by the French pioneers, was also to change the course of image reproduction. Daguerre, like other businessmen-scientists of his time, was well prepared for the popular spread of photography as a medium for the mass reproduction of images.

A pupil of Prévost, he had designed panoramas and dioramas from 1822, later bringing in live action and sound to enhance the attractions of these large-scale scenes of cities, battles and famous events, painted on translucent linen and transformed by lighting. His first experiments in photography used, in fact, an adapted camera obscura. Just as tellingly for the future, the worldly Daguerre made sure that his contract with Niépce in 1829 enjoined them ‘to gain all possible advantages from this new industry’. Daguerre’s ‘showmanship’ – his business flair as well as his sense of public spectacle, from dioramas to ballooning – did indeed connect the new technologies of vision and motion; cinema films are still viewed as panoramas in dark spaces, and remain epic rather than intimate in scale.

Balzac, like Dickens and Zola, charts in his novels the passage from classical stasis to romantic flux in nineteenth-century Europe. Motion was a key concept and emblem of the period, from cities and empires to railroads and mass spectacle. The sense of dynamism which this implied, and of which film was both literal figure and late metaphor, was passed on to later generations by way of the aptly named ‘motion pictures’ and indeed by a host of artistic and political ‘movements’ which typically came, like light, in waves.

Crary’s revisionism attempts to avoid the dangers of simple teleology, or reading history backwards as a series of inevitable steps from the present to the past. It resists the centrifugal tendency of each period, including our own, to construct the past in its own image. At the same time, the nineteenth century’s own ideology of progress and its cult of the ‘invention’ are an implicit part of its cultural history. In this sense, the making of ‘moving pictures’, which culminated in the 1890s, was indeed a goal to which many scientists and others consciously moved by diverse and overlapping paths. The concept of progress embodies this ‘forward-looking’ self-image and led to such real effects as cinema itself.

The span of proto-cinema goes from Philip De Loutherberg’s ‘Eidophusikon’ – exhibited in England from 1781 and combining screen images with sound effects – and the spread of ‘Phantasmagorias’ in Paris, London and New York from the 1790s to 1800. It does not seem illegitimate to connect the exploits of Daguerre, a photographer and balloonist who started as a designer of dioramas, with Grimion-Samson’s 1900 ‘Cineorama’ which took circular 360° views on 70mm film from a balloon, or with James White’s panoramas of the World Fairs, or with Edwin Porter’s similar use of a fluid-panning59 tripod for shots of the Buffalo ‘Electric Tower’ in 1900. Film historian Tom Gunning argues that these and similar scenographic ventures make up a pre-narrative ‘cinema of attractions’ which the advent of the single-screen drama film forced underground – and partly into the avant-garde – after 1907.60

It was in a climate of expanding industry and invention from 1820–50 that the idea of an artistic avant-garde materialised. It was prefigured in the bonds between the painter Jacques-Louis David’s classicism and the Revolution of 1789, when David was practically the official artist of the new regime, organising popular celebrations, or ‘street-art’, as well as painting its historical icons. But the avant-garde (named as such in the 1820s) first flourished in a later revolutionary France, erupting in 1848, to which artists and intellectuals were central. ‘Barriers are falling and the horizons expanding’, wrote a critic at the time. Progressive art and revolutionary politics were emblematically united when Delacroix’s inflammatory Liberty Guiding the People was exhibited for the first time since the previous political uprising of 1830.

For the next thirty years the term ‘avant-garde’ denoted radical or advanced activity both social and artistic.61 The utopian socialist Saint-Simon had coined the term to designate the élite leadership of artists, scientists and industrialists in the new century. At first the avant-garde was led by social rather than stylistic concerns. Later it took on overtones of more extreme rebellion. Courbet embodied the artist as social critic and outcast (he was exiled after the fall of the Paris Commune in 1871), and his influence preserved the link between the avant-garde and social realism through the 1860s and beyond.

But, stripped of its historical quotation marks, as Linda Nochlin recommends, the avant-garde in art can more readily be seen to begin with Manet. Manet’s realism was nothing if not critical. His free brushwork, allusive and ironic subject-matter and formal doubling of space and reflection (all of which can be seen in the Bar at the Folies Bergère) are far from the social realism of progressive art, even though he shared its republican sympathies. At this point the idea of an avant-garde passes through the crucible of art. By the time of Matisse, Picasso, Stravinsky and Diaghilev, avant-garde simply meant new, the latest modern thing. Fine distinctions between modernism and the avant-garde were yet to come. However,...