![]()

Chapter 1

Between Space, Site and Screen

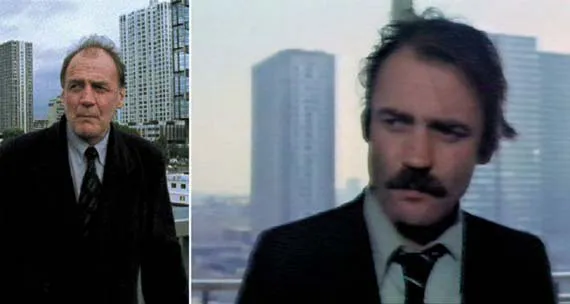

Pierre Huyghe

L’Ellipse, 1998

Beta Digital, 13 minutes

Courtesy Galerie Marian Goodman Paris / New York

Everything, then, passes between us. This ‘between’, as its name implies, has neither a consistency nor continuity of its own. It does not lead from one to the other; it constitutes no connective tissue, no cement, no bridge. Perhaps it is not even fair to speak of a ‘connection’ to its subject; it is neither connected nor unconnected; it falls short of both; even better, it is that which is at the heart of a connection, the interlacing … of strands whose extremities remain separate even at the very center of the knot.

Jean-Luc Nancy, Being Singular Plural.1

Introduction

Over the past decade, major museums have repeatedly sought to explore and stage a history of dialogue between art and film, whilst in parallel, curators and programmers have begun to reflect upon the various ways in which being ‘between’ might be a mode particular to artists’ cinema.2 Charting some of these forms of ‘between-ness’, Stephanie Schulte Strathaus emphasizes that many artists were first attracted to the moving image in the 1960s in order ‘to create a counterculture to commercial movie theaters’. She suggests that the distinction between art and film, together with ‘the differentiation between commercial and independent film’, served to constitute a ‘space between’ and she goes on to explore this space by highlighting the relationship between film programming and montage, concluding that ‘a program always needs at least two films that together form this “in-between,” this third space that the viewer will remember together with the films themselves.’3 This comment underscores the complex interplay between the site and space of the auditorium, the experience of the ‘film programme’ as a distinct temporal entity and the processes of remembering through which cinema acquires meaning.

It is also possible to conceptualize artists’ cinema through reference to broader notions of the interstitial, intermediate or in-between, as encountered in architectural and economic theory. In an analysis of art and architecture that references a number of moving image works, Jane Rendell invokes Edward Soja’s triad of space, time and the social in order to theorize a critical spatial practice that can emerge in ‘a place between’ art and architecture.4 A different approach to ‘between-ness’ can be found in studies of organizational culture and the knowledge economy. For example, Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello highlight the importance of mediating activities in the creation of networks and economies that are organized around the ‘project’. They perceive the activity of mediating as increasingly identified and valued in its own right, ‘separated from the other forms of activity it had hitherto been bound up with’.5 Informed by these disparate perspectives, this chapter explores the various intersections and interstices where artists’ cinema comes into being, extending from the ‘space-in-between’ of the multi-screen installation, to the interplay between production and exhibition in site-based works, and the forms of translation and exchange shaping the development of the ‘cine-material’ practices discussed in Chapter 5.

Between Genealogies

As I have already suggested, the term ‘artists’ cinema’ does not signify a unified or coherent historical formation. Instead, it refers to a series of competing claims made for and by artists and art practice in relation to cinema and the wider context of moving image culture. Some of these claims are overtly ‘genealogical’, seeking to frame artists’ cinema as an extension of another form of art practice, such as experimental film, post-minimalist installation, video art or performance.6 In recent years, critical attention seems to have focused on the ‘gallery film’ as a distinct area of moving image practice, one with a particular debt to experimental film. Chris Dercon has offered a typology of artists’ film, in which the first ‘layer’ consists of the film avant-garde (Maya Deren, Michael Snow, Paul Sharits and Kenneth Anger, among others) while the second is an ‘artistic avant-garde’ working with video installation (Bruce Nauman, Gary Hill and Bill Viola).7 Drawing upon Dercon’s analysis, Catherine Fowler proposes that the gallery films (by artists such as Steve McQueen, Stan Douglas, Shirin Neshat, Douglas Gordon and Eija-Liisa Ahtila) constitute a third ‘layer’. Noting that references to classical or popular cinema are often made explicit, she argues that the gallery film’s debt to experimental filmmaking is less likely to be acknowledged.

Others have also called attention to a degree of amnesia in the production and exhibition of artists’ cinema. Writing in 2000, Chris Darke charts the migration of cinema into the gallery during the 1990s and notes an attendant erasure of critical memory with respect to video art. In fact, he suggests that the rise of the gallery film in the UK has produced a ‘curious effect … where a new generation of artists has elected to work with video and, in so doing, has frequently aped the work of innovators in the form such as Vito Acconci, Bruce Nauman and Marina Abramovic almost as though they had never existed.’8 Interestingly, Darke also suggests that the gallery has been cast as an ‘alternative site’, in opposition to an increasingly pervasive ‘Hollywood monoculture’. This monoculture, encompassing video games and mobile media as well as film and television, addresses the viewer as consumer rather than citizen. In contrast, Darke posits that the experience of the moving image in the gallery appears to offer a respite from the commercialization and privatization of domestic space.

An alternative lineage is suggested in a short typology of film and video space developed by curator Chrissie Iles which notes a possible connection between the evolution of artists’ film and video in the 1960s and the modes of large-scale display that were associated with contemporary commercial events such as the World’s Fair of 1964 in New York.9 She places particular emphasis on the exploration of public space within artists’ film and video during the 1960s, noting a recurrent desire to break down the boundaries between public and private space, and offering a complex typology that extends from the ‘mirrored space’ of Dan Graham to the ‘adversarial space’ of Bruce Nauman, the ‘durational space’ of Peter Campus and the ‘theatrical space’ of Vito Acconci. These differences were explored in the exhibition ‘Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art 1964–1977’, curated by Iles at the Whitney Museum (2001–2002). In her contribution to the exhibition catalogue, she cites various philosophical precedents for the creation of a hybrid or intermediate space, a space of enquiry where the light is ‘dimmed’ but not extinguished. She also notes that post-minimalist art brought about a transformation of ‘actual space’ (whether in the form of the gallery, museum or ‘alternative space’) into a perceptual field that often took the form of ‘a hybrid of white cube and black box’.10 This notion of a hybrid is intriguing, pointing towards a possible connection between the practices of the later 1960s and early 1970s and the more recent explorations of the ‘cine-material’, theorized in Chapter 5.

For some commentators, the self-consciously ‘cinematic’ practices of the 1990s can be seen to extend (or at least reiterate) the perceptual and phenomenological investigations of the 1960s and 70s. Writing in 2000, Iles suggests that contemporary ‘film and video space has become the location of a radical questioning of the future of both aesthetic and social space’.11 Her relatively upbeat view of contemporary artists’ cinema is, however, contested by others. Catherine Elwes, an artist with a longstanding involvement in video practice in the UK, has emphasized an opposing trajectory. She charts the movement of artists’ video from the margins to the mainstream, extending from Nam June Paik’s experiments within and beyond the gallery during the 1960s to the commercial acceptance, if not dominance, of video installation in the 1990s. Elwes is not convinced by claims that the gallery has been transformed into a ‘newly radicalised “cinematic” space’ by virtue of the presence of the projected image:

In fact, dispensing with the television set, and replacing it with pure cinemascope illusionism elevates video and film to a kind of electronic mural painting in the grand manner, enveloped in the silence of the rarefied quasi-cathedrals of art that both commercial and public galleries have turned into. The ritualised, communal, proletarian experience – the eating, drinking, smoking and necking that accompanied the theatrical display of cinema – is also lost.12

Evidently, there are many occlusions and absences within this critique. Elwes seems to mourn the loss of the ‘marginal’, without fully questioning this notion and by emphasizing the silence of the gallery she does not fully account for the significance of sound in film and video installation since the 1990s. But even though she is nostalgic for an idealized communality of the cinema, she does acknowledge the possibility of a form of public engagement and discourse that is particular to the gallery. As an example of this, she describes an experience of public scrutiny (and self-scrutiny) in the gallery. She notes that while viewing Ann-Sofi Siden’s exhibition Warte Mal! Prostitution after the Velvet Revolution (2002), focusing on the experiences of women involved in cross-border prostitution, she was very aware of being ‘watched watching’ by her fellow gallery-goers.13 This experience is specifically associated with the activity of witnessing, in which the gallery offers a platform for experiential accounts or testimonies of marginalization or exclusion. This seems to suggest a convergence between two overtly pedagogical conceptions of public space. One is linked to the ‘exhibitionary complex’ and the history of the museum as an institution in which appropriate behaviour is modelled.14 The other is aligned to the instructional or informative aspects of public service media (significantly undermined by the process of commercialization described by Darke, among others). Indeed, like Darke, Elwes pays particular attention to the changing relationship between art practice and public service television within the UK context, and her analysis hints at the various ways in which certain forms of film and video production, traditionally associated with television, may have migrated towards the gallery.

An alternative genealogical point of reference for contemporary artists’ cinema can be located in Jonathan Walley’s account of ‘paracinema’, a term that refers to the exploration of ‘cinematic properties outside the standard film apparatus’ in the work of Anthony McCall and others during the 1970s.15 The term ‘expanded cinema’ has also been widely used (particularly within UK contexts) to describe works that extend or contest the limits of cinema: sometimes operating outside the domain of theatrical exhibition or involving the adaptation or multiplication of the projection apparatus. Walley’s concept of paracinema is associated with a somewhat narrower strand of practice, with Anthony McCall’s Long Film for Ambient Light (1975) functioning as a key example. This was an overtly ‘locational’ work, in that it ‘consisted of an empty Manhattan loft, its windows covered by diffusion paper, lit in the evening by a single bare light bulb hanging from the ceiling’.16 In the absence of a film, or even a projector, attention is directed in this work towards the phenomenological properties of the loft as both site and space.

Speaking about Long Film within the context of the exhibition ‘Into the Light’ in December 2001, McCall emphasizes that it ‘was inspired by a particular context, that of the Idea Warehouse … a large loft space on Reade Street that was connected to The Clocktower’.17 It is worth noting that this context was temporal as well as spatial, because McCall was invited to participate in a group show in which each artist was offered the space for two days. His installation began at noon on June 18, 1975 and finished exactly twenty-four hours later. According to Walley, this exploration of cinema beyond the apparatus was informed both by the general tendency towards dematerialization in contemporary art during the late 1960s and early 1970s18 and by an overtly historicized concept of the medium of film, indebted to Bazin and Eisenstein. Animated by Bazin’s ‘Myth of Total Cinema’ and Eisenstein’s analysis of montage, Walley sees the work of McCall and others as premised on the notion that ‘the film medium … is not a timeless absolute but a cluster of historically contingent materials that happens to be, for the time being at least, the best means for creating cinema.’19 Walley is also specifically interested in paracinema as a transitional response to the shifts towards a ‘post-medium age’ ushered in by Minimalism and Conceptual art. In particular, he suggests that by embracing cinema as their ‘medium’, filmmakers such as McCall could explore the conceptual dimensions of cinema without being limited to the medium of film, so that they did not need to ‘reiterate the materials of film again and again.’20

Furthermore, this re-conceptualization of medium specificity can be understood in economic terms, through reference to the relationship between avant-garde film and the art market. Walley emphasizes that Structural film occupied an oppositional position with respect to the art market during the 1970s, and he cites David E. James in support of this position:

Though Structural film was an avant-garde art practice taking place within the parameters of the art world, it was unable to achieve the centrally important function of art in capitalist society: the capacity for capital investment. Massive public indifference to it, its inaccessibility to all but those of the keenest sensibility, and finally its actual rather than merely ostensible inability to be incorporated excluded it from the blue-chip functions, the mix of real estate and glamour, that floated the art world … Film’s inability to produce a readily marketable object, together with the mechanical reproducibility of its texts, set very narrow limits to the possibility of Structural film’s being turned into a commodity.21

The situation with respect to contemporary artists’ cinema is, however, rather different. As Walley has pointed out elsewhere, contemporary artists working with the moving...