- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

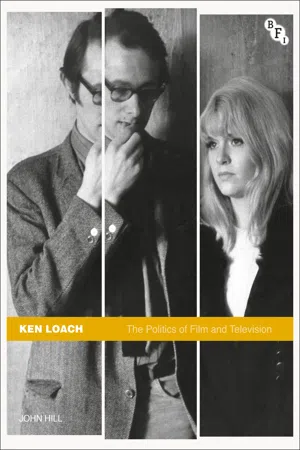

John Hill's definitive study looks at the career and work of British director Ken Loach. From his early television work (Cathy Come Home) through to landmark films (Kes) and examinations of British society (Looking For Eric) this landmark study reveals Loach as one of the great European directors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ken Loach by John Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Towards ‘a new drama for television’

Diary of a Young Man and The End of Arthur’s Marriage

Ken Loach was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire on 17 June 1936. Born into a respectable working-class family (his father was a foreman in a machine-tools factory), Loach succeeded in winning a scholarship that allowed him to go to grammar school. A spell of National Service in the RAF followed before Loach proceeded to St Peter’s College, Oxford to read Law. At Oxford he became active in the Oxford University Drama Society (of which he became President). Opting for the theatre rather than law on graduation, he worked as an actor before winning sponsorship from ABC Television to train as a director at Northampton Repertory Company. In a subsequent move that might be said to have transformed his life, he then joined the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) as a trainee television director in August 1963.

The time at which Loach entered the BBC constituted a period of significant change both within television and society more generally. In the case of the BBC, Hugh Greene had become the new Director-General at the beginning of 1960. In a speech in Germany in 1958, Greene had boldly declared that public-service television could ‘dare to be experimental and adventurous’ and he subsequently presided over what has been widely regarded as a period of liberalisation and innovation at the BBC.15 In this, he was provided with extra ammunition by the Report of the Committee on Broadcasting 1960 (chaired by Sir Harry Pilkington and presented to Parliament in June 1962). Although the growing popularity of ITV during the 1950s had placed the BBC under increasing pressure to increase audience share in order to justify the continuation of the licence fee, the Pilkington Report was clear that television should not simply give ‘the public what it wants’, suggesting how this could lead to ‘a lack of variety and originality’ and ‘an adherence to what was “safe”’.16 As a result, the Report suggested it should be the responsibility of television to ‘focus a spotlight’ on ‘the growing points’ of social change and to ‘be ready and anxious to experiment, to show the new and unusual, to give a hearing to dissent’.17 In this way, as John Caughie suggests, the Pilkington Report not only restated the importance of public-service broadcasting in the face of commercial competition but also offered an ‘enabling discourse’ that lent support to innovation and experiment within the BBC.18

Although innovation was evident across a range of genres (as in the case of the late-night satirical programme That Was the Week That Was, launched in 1962), it would be fair to say that it was in the area of television drama that the readiness to experiment, and to give expression to new and dissenting voices, was most evident. A significant contributory factor in this respect was the arrival of Sydney Newman as the BBC’s Head of Drama in January 1963. Newman was a Canadian who had moved to Britain in 1958 to take over as Head of Drama at the ITV company, ABC TV. Inspired by the new directions in British theatre inaugurated by John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger in 1956, he quickly acquired a reputation for encouraging new kinds of writing and directing attuned to ‘the dynamic changes taking place in the Britain of today’ by virtue of his productions for ABC’s ‘Armchair Theatre’ such as Alun Owen’s No Trams to Lime Street (tx. 18 October 1959), Clive Exton’s Where I Live (tx. 10 January 1960) and Harold Pinter’s A Night Out (tx. 24 April 1960).19 On his arrival at the BBC, one of Newman’s first moves was to reorganise the Drama Department into different groups responsible for series, serials and single plays and encourage the emergence of popular new programmes such as Doctor Who, launched in 1963. However, Newman was also conscious, following Pilkington, that plays should be regarded as ‘more than trivial entertainment’ and that his department should produce plays that sought not only to ‘interpret their age’ but also to do so through ‘a new kind of dramatic communication’.20 In this respect, Newman was also articulating the growing sense of dissatisfaction with the prevailing conventions of television drama that had already begun to gather momentum within the BBC.

‘Nats Go Home’

For while ABC’s Armchair Theatre may have succeeded in introducing new kinds of contemporary material into television drama, and encouraged a freer use of cameras, there was still a strong sense among a growing number of producers and writers that television had failed to find the new forms of expression equivalent to those found in the ‘new waves’ of British theatre and cinema. While this could be attributed, in part, to the constraints of technology, it was also the result of aesthetic choices. In the early 1960s, the bulk of television drama was still shot in the studio, employing a limited number of sets and often transmitted live. Although the introduction of videotape in 1958 had allowed drama to be pre-recorded, it remained expensive and cumbersome to use and extensive editing was discouraged. As a result the recording of television drama remained very close to the live broadcast, normally consisting of a continuous recording following a few days of studio rehearsal. Thus, while John Caughie draws attention to the increased camera mobility involved in the recording of television drama during the late 1950s and early 1960s, he also suggests how the dominant aesthetic of television remained wedded to the idea of theatrical performance and the use of the studio as a ‘performative space’.21 Although this aesthetic was regarded by some as well suited to the specific characteristics of the television medium, others were coming to the conclusion that television drama must break free of the ‘proscenium presentation’ associated with traditional forms of television drama.22 As early as 1956, the Head of Television Drama at the BBC, Michael Barry, had established an Experimental Group to consider the role of experimental television programmes in the development of new production methods, including the exploration of ‘new methods of storytelling and … stories that cannot be told in conventional form’.23 This eventually led to the establishment of the short-lived Langham Group, led by Anthony Pélissier, which became responsible for a small number of experimental dramas, including Torrents of Spring (tx. 21 May 1959) and Mario (tx. 15 December 1959), devoted to the testing of new techniques. Although the Group explored new methods of camera movement, montage and sound, its efforts met with a mixed response and critics attacked the Group’s work for being too preoccupied with experiment for its own sake.24

Nevertheless, the Group’s enthusiasm for moving beyond the limits of conventional television drama, and employing more visual forms of storytelling, survived in a growing campaign against what came to be identified as television ‘naturalism’. This was expressed most famously in a manifesto, ‘Nats Go Home’, written by Troy Kennedy Martin and published in Spring 1964 in Encore, a magazine strongly associated with the new currents in British theatre. As its title indicates, the main focus of Kennedy Martin’s critique is ‘naturalism’ which he insists is ‘the wrong form for drama for the medium’.25 From a contemporary point of view, the choice of the term ‘naturalism’ may appear to be an odd one, given that it is not the features commonly associated with naturalism (such as the representation of contemporary realities) that are Kennedy Martin’s main object of attack. However, at the time the manifesto was written, the idea of ‘naturalism’ was largely understood to refer to the ‘theatrical’ approach to television drama that prevailed at the time and it is certainly this that Kennedy Martin was criticising when he declared that ‘[a]ll drama which owes its form or substance to theatre plays is OUT’.26 For Kennedy Martin, this theatrical – or ‘naturalist’ – approach to television drama was characterised by a number of key features. ‘“Nat” plays’, he argues, involve the telling of ‘a story by means of dialogue’ rather than other means; they work within ‘a strict form of natural time’ in which ‘studio-time equals drama-time equals Greenwich Mean Time’, and they rely heavily upon the use of close-ups – the photographing of ‘faces talking and faces reacting’ – which it was assumed would act ‘subjectively upon the viewer’ to generate emotional involvement in ‘a character’s predicament’. For Kennedy Martin, therefore, the ambition of ‘the new drama’ had to be to challenge these conventions and to ‘free the camera from photographing dialogue … free the structure from natural time’ and abandon the pursuit of subjective identification with characters through the exploitation of ‘the total and absolute objectivity of the television camera’.27 Kennedy Martin’s arguments are not always as clear as they might be and, subsequently, there has been debate regarding the precise meaning of some the terms he employs, including his notion of the television camera’s ‘objectivity’.28However, Kennedy Martin’s essay was not simply a piece of theory but was accompanied by an extract from a screenplay that he and John McGrath had written (and which was then under negotiation with the BBC).29 Although, for a time, it looked as though it would not proceed to production, the script subsequently became a six-part series, entitled Diary of a Young Man, broadcast on BBC1 during August and September 1964. The original idea appears to have been that McGrath would direct the series. In the event, however, the job went to two relative newcomers: Kenneth Loach (who directed Episodes 1, 3 and 5) and Peter Duguid (who directed the rest).30

‘Teletales’: Catherine (1964)

Although Diary of a Young Man was accompanied by an ‘experimental’ manifesto, the series itself was conceived as a mainstream production, broadcast on a primetime Saturday slot on BBC1 and featured on the cover of the Radio Times. It is therefore testimony to the Drama Department’s spirit of adventure (or possibly shortage of TV directors) that the direction of the series should be entrusted to two relative novices. As already noted, Loach had only joined the BBC the previous year when he had been recruited for a trainee directors’ course established in anticipation of the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Towards ‘a new drama for television’: Diary of a Young Man and The End of Arthur’s Marriage

- 2. ‘Urgently contemporary and socially relevant’: From A Tap on the Shoulder to Up the Junction

- 3. Blurring ‘the distinction between fact and fiction’: Cathy Come Home, In Two Minds and The Golden Vision

- 4. ‘The play of political advocacy’: The Big Flame and The Rank and File

- 5. From Television into Film: Poor Cow, Kes and Family Life

- 6. ‘This is our history’: Days of Hope

- 7. ‘The UK’s pre-eminent arthouse director’: From Television Censorship to ‘Art Cinema’

- 8. ‘It’s a free world’: Social Change and Class from Riff-Raff to Looking for Eric

- 9. ‘What might have been’: Land and Freedom and The Wind That Shakes the Barley

- Select Bibliography

- Filmography

- Index

- List of Illustrations

- eCopyright