- 456 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Circuit Designer's Companion

About this book

The Circuit Designers Companion, Third Edition, provides the essential information that every circuit designer needs to produce a working circuit, as well as information on how to make a design that is robust, tolerant to noise and temperature, and able to operate in the system for which it is intended. It looks at best practices, design guidelines, and engineering knowledge gained from years of experience, and includes practical, real-world considerations for components and printed circuit boards (PCBs) as well as their manufacturability, reliability, and cost. Organized into nine chapters, the book begins with a discussion of grounding and wiring of electronic or electrical circuits, when to consider grounding, and the main factors that must be taken into account when designing a new PCB. It then introduces the reader to passive components such as resistors and capacitors, potentiometers and inductors, and crystals and resonators, as well as active components like diodes, thyristors and triacs, bipolar transistors, junction field-effect transistors, metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs), and insulated gate bipolar transistors (IGBTs). It also describes high-speed digital circuit design and analog integrated circuits, including operational amplifiers and comparators, and power supplies such as batteries. The final two chapters focus on electromagnetic compatibility and the latest advances in electronics, along with safety considerations in the design of electronic equipment. This book is an invaluable resource for circuit designers and practicing electronics engineers, electronic engineering students, and professors.

- An invaluable companion for circuit designers and practicing electronics engineers – gives best practices, design guidelines and engineering knowledge gleaned from years of experience

- Includes practical, real-world considerations for components, PCBs, manufacturability, reliability and cost, enabling engineers to design and troubleshoot faster, cheaper and more effectively

- Contains new material on design tools and communication devices, high-speed digital circuit design, simulation methods and testing

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Circuit Designer's Companion by Peter Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Grounding and wiring

Chapter Outline

1.1 Grounding

When to consider grounding

1.1.1 Grounding within one unit

1.1.2 Chassis ground

1.1.3 The conductivity of aluminum

Other materials

1.1.4 Ground loops

1.1.5 Power supply returns

Varying loads

Power rail feed

Conductor impedance

1.1.6 Input signal ground

Connection to O V elsewhere on the PCB

Connection to O V within the unit

External ground connection

1.1.7 Output signal ground

Avoiding the common impedance

1.1.8 Inter-board interface signals

Partitioning the signal return

1.1.9 Star-point grounding

1.1.10 Ground connections between units

Breaking the ground link

1.1.11 Shielding

Which end to ground for LF shielding

Electrostatic screening

Surface transfer impedance

1.1.12 The safety earth

1.2 Wiring and cables

1.2.1 Wire types

Wire inductance

Equipment wire

Wire-wrap wire

1.2.2 Cable types

1.2.3 Power cables

1.2.4 Data and multicore cables

Data communication cables

Structured data cable

Shielding and microphony

1.2.5 RF cables

1.2.6 Twisted pair

1.2.7 Crosstalk

Digital crosstalk

1.3 Transmission lines

Transmission line effects

Critical lengths for pulses

1.3.1 Characteristic impedance

1.3.2 Time domain

Forward and reflected waves

Ringing

The Bergeron diagram

The uses of mismatching

1.3.3 Frequency domain

Standing wave distribution versus frequency

Impedance transformation

Lossy lines

Understanding the transmission line impedance graphically

1.1 Grounding

A fundamental property of any electronic or electrical circuit is that the voltages present within it are referenced to a common point, conventionally called the ground. This term is derived from electrical engineering practice, when the reference point is often taken to a copper spike literally driven into the ground. This point may also be a connection point for the power to the circuit, and it is then called the 0 V (nought-volt) rail, and ground and 0 V are frequently (and confusingly) synonymous. Then, when we talk about a five-volt supply or a minus-twelve-volt supply or a two-and-a-half-volt reference, each of these are referred to the 0 V rail.

At the same time, ground is not the same as 0 V. A ground wire connects equipment to earth for safety reasons, and does not carry a current in normal operation. However, in this chapter the word “grounding” will be used in its usual sense, to include both safety earths and signal and power return paths.

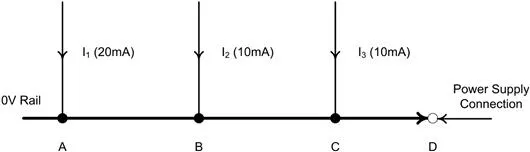

Perhaps the greatest single cause of problems in electronic circuits is that 0 V and ground are taken for granted. The fact is that in a working circuit there can only ever be one point which is truly at 0 V; the concept of a “0 V rail” is in fact a contradiction in terms. This is because any practical conductor has a finite non-zero resistance and inductance, and Ohm’s law tells us that a current flowing through anything other than a zero impedance will develop a voltage across it. A working circuit will have current flowing through those conductors that are designated as the 0 V rail and therefore, if any one point of the rail is actually at 0 V (say, the power supply connection) the rest of the rail will not be at 0 V. This can be illustrated with the example in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1 Voltages along the 0 V rail

Assume the 0 V conductor has a resistance of 10 mΩ/inch and that points A, B, C and D are each one inch apart. The voltages at points A, B and C referred to D are:

Assume the 0 V conductor has a resistance of 10 mΩ/inch and that points A, B, C and D are each one inch apart. The voltages at points A, B and C referred to D are:

Now, after such a trenchant introduction, you might be tempted to say well, there are millions of electronic circuits in existence, they must all have 0 V rails, they seem to work well enough, so what’s the problem? Most of the time there is no problem. The impedance of the 0 V conductor is in the region of milliohms, the current levels are milliamps, and the resulting few hundred microvolts drop doesn’t offend the circuit at all; 0 V plus 500 μV is close enough to 0 V for nobody to worry.

The difficulty with this answer is that it is then easy to forget about the 0 V rail and assume that it is 0 V under all conditions, and subsequently be surprised when a circuit oscillates or otherwise doesn’t work. Those conditions where trouble is likely to arise are:

• where current flows are measured in amps rather than milli- or microamps;

• where the 0 V conductor impedance is measured in ohms rather than milliohms;

• where the resultant voltage drop, whatever its value, is of a magnitude or in such a configuration as to affect the circuit operation.

When to consider grounding

One of the attributes of a good circuit designer is to know when these conditions need to be carefully considered and when they may be safely ignored. A frequent complication is that you as circuit designer may not be responsible for the circuit’s layout, which is handed over to a layout draughtsman (who may in turn delegate many routing decisions to a software package). Grounding is always sensitive to layout, whether of discrete wiring or of printed circuits, and the designer must have some knowledge of and control over this if the design is not to be compromised.

The trick is always to be sure that you know where ground return currents are flowing, and what their consequences will be; or, if this is too complicated, to make sure that wherever they flow, the consequences will be minimal. Although the above comments are aimed at 0 V and ground connections, because they are the ones most taken for granted, the nature of the problem is universal and applies to any conductor through which current flows. The power supply rail (or rails) is another special case where conductor impedance can create difficulties.

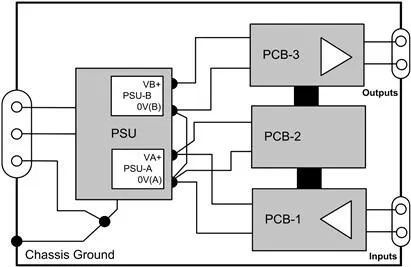

1.1.1 Grounding within one unit

In this context, “unit” can refer to a single circuit board or a group of boards and other wiring connected together within an enclosure such that you can identify a “local” ground point, for instance the point of entry of the mains earth. An example might be as shown in Figure 1.2. Let us say that printed circuit board (PCB) 1 contains input signal conditioning circuitry, PCB2 contains a microprocessor for signal processing and PCB3 contains high-current output drivers, such as for relays and for lamps. You may not place all these functions on separate boards, but the principles are easier to outline and understand if they are considered separately. The power supply unit (PSU) provides a low-voltage supply for the first two boards, and a higher-power supply for the output board. This is a fairly common system layout and Figure 1.2 will serve as a starting point to illustrate good and bad practice.

FIGURE 1.2 Typical intra-unit wiring scheme

1.1.2 Chassis ground

First of all, note that connections are only made to the metal chassis or enclosure at one point. All wires that need to come to the chassis are brought to this point, which should be a metal stud dedicated to the purpose. Such connections are the mains safety earth (about which more later), the 0 V power rail, and any possible screening and filtering connections that may be required in the power supply itself, such as an electrostatic screen in t...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Grounding and wiring

- Chapter 2. Printed circuits

- Chapter 3. Passive components

- Chapter 4. Active components

- Chapter 5. Analog integrated circuits

- Chapter 6. Digital circuits

- Chapter 7. Power supplies

- Chapter 8. Electromagnetic compatibility

- Chapter 9. General product design

- Appendix: Standards

- Bibliography

- Index