eBook - ePub

Jerusalem 1900

The Holy City in the Age of Possibilities

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jerusalem 1900

The Holy City in the Age of Possibilities

About this book

Perhaps the most contested patch of earth in the world, Jerusalem's Old City experiences consistent violent unrest between Israeli and Palestinian residents, with seemingly no end in sight. Today, Jerusalem's endless cycle of riots and arrests appears intractable—even unavoidable—and it looks unlikely that harmony will ever be achieved in the city. But with Jerusalem 1900, historian Vincent Lemire shows us that it wasn't always that way, undoing the familiar notion of Jerusalem as a lost cause and revealing a unique moment in history when a more peaceful future seemed possible.

In this masterly history, Lemire uses newly opened archives to explore how Jerusalem's elite residents of differing faiths cooperated through an intercommunity municipal council they created in the mid-1860s to administer the affairs of all inhabitants and improve their shared city. These residents embraced a spirit of modern urbanism and cultivated a civic identity that transcended religion and reflected the relatively secular and cosmopolitan way of life of Jerusalem at the time. These few years would turn out to be a tipping point in the city's history—a pivotal moment when the horizon of possibility was still open, before the council broke up in 1934, under British rule, into separate Jewish and Arab factions. Uncovering this often overlooked diplomatic period, Lemire reveals that the struggle over Jerusalem was not historically inevitable—and therefore is not necessarily intractable. Jerusalem 1900 sheds light on how the Holy City once functioned peacefully and illustrates how it might one day do so again.

In this masterly history, Lemire uses newly opened archives to explore how Jerusalem's elite residents of differing faiths cooperated through an intercommunity municipal council they created in the mid-1860s to administer the affairs of all inhabitants and improve their shared city. These residents embraced a spirit of modern urbanism and cultivated a civic identity that transcended religion and reflected the relatively secular and cosmopolitan way of life of Jerusalem at the time. These few years would turn out to be a tipping point in the city's history—a pivotal moment when the horizon of possibility was still open, before the council broke up in 1934, under British rule, into separate Jewish and Arab factions. Uncovering this often overlooked diplomatic period, Lemire reveals that the struggle over Jerusalem was not historically inevitable—and therefore is not necessarily intractable. Jerusalem 1900 sheds light on how the Holy City once functioned peacefully and illustrates how it might one day do so again.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Underside of Maps: One City or Four Quarters?

If the Old City is divided on today’s maps, in Hebrew as in the European languages, to the four nineteenth-century introduced community quarters and not to quarters which existed along centuries, it is because the foundations of its modern cartography were laid by people who came from outside and not from the city itself.

—Adar Arnon, “The Quarters of Jerusalem in the Ottoman Period”

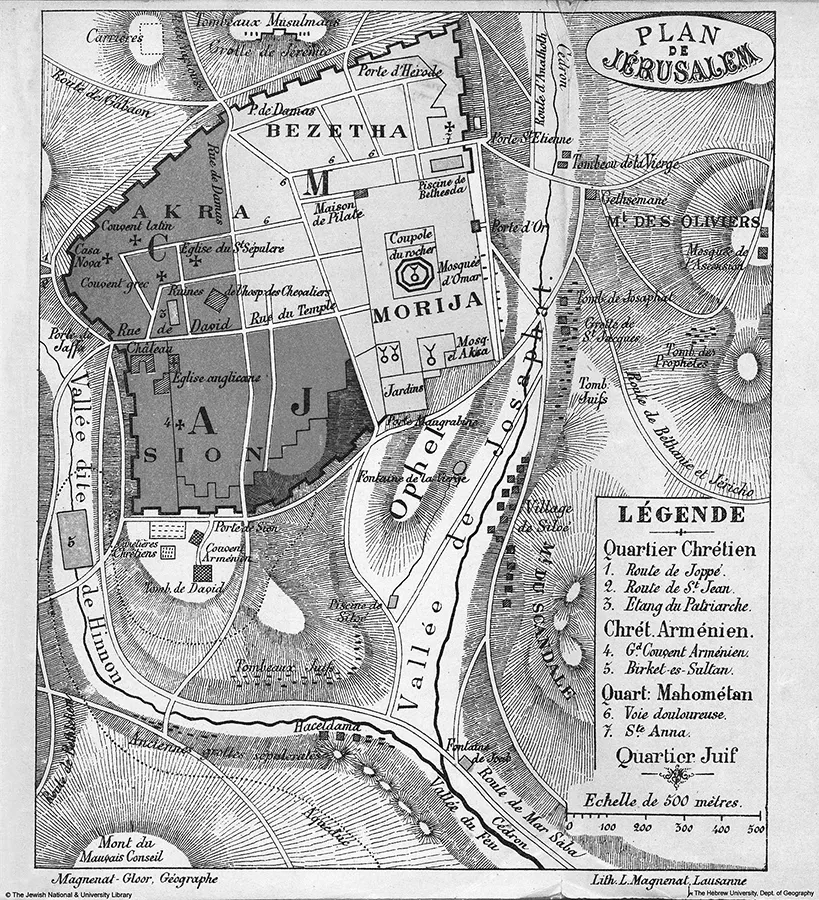

“How many parts to Jerusalem?” This is often the general reader’s reaction to current works on the holy city, which, even before discussing its location and history, begin by splitting it up into four pieces, presenting the reader with four rectilinear segments, painstakingly drawn as if they were four apple slices neatly arranged on a dessert plate (“Jewish,” “Christian,” “Muslim,” and “Armenian” quarters). Each of these presumed quarters is drawn in a different bright color. The choice of colors might vary, but the intention is always the same: the city is compartmentalized, and care is taken so as not to go over the supposedly inherent dividing lines (fig. 1). Jerusalem, the object of the study, even barely broached is already dismembered. The rhetoric is always the same, artful but misleading: to grasp the “complexity” of the three-times-holy city, we are told, we must first understand its “diversity.” In reality, however, this praiseworthy statement of intent is followed by the opposite process: the complexity of population dynamics in the different parts of the city is set aside to give way to a simplistic classification resembling a childhood puzzle in four colors.

Figure 1. Map published in 1881, showing that the representation of the city in four quarters took hold gradually, at this point still with some differences compared to standard present-day representations. The quarter called here “Mahométan” (“M,” in the northeast) comprises the row of mosques, but also the area situated in front of the Wailing Wall; the “Jewish” quarter (“Quartier Juif,” indicated by “J,” to the south) is reduced to the remaining area, deprived in its eastern part of access to the Wailing Wall.

A ROUGH-CUT CARTOGRAPHY

In both travel guides and scholarly works, Jerusalem is usually presented as the juxtaposition of four clearly identified sections: the “Muslim quarter” in the northeast part of the old city, the “Christian quarter” in the northwest, the “Armenian quarter” in the southwest, and the “Jewish quarter” in the southeast. To these is generally added the location called the “Haram esh-Sharif,” the “Esplanade of the Mosques,” “Mount Moriah,” or “Temple Mount,” depending on the author’s affiliations. The new city, which grew up outside the walls in the 1860s and already held half the total population in 1900, usually does not feature in this first cartographic contact, probably because it differs too much from the assumed expectations of the reader.

As for the city within the walls, the description of these “quarters” varies from one work to another, and the order of priority reveals more or less subtly the authors’ political choices or religious affiliations. Thus, some writers begin with the “Muslim quarter,” which had the largest number of inhabitants at the end of the nineteenth century. Others arrange the quarters following the order of revelation of the major monotheistic religions (Jewish quarter, then Christian quarter, then Muslim quarter), with the Armenian quarter usually relegated to the end of the list, regardless of the order of description, and contradicting the notion of a “Christian quarter” that would logically include it. Still other authors, particularly those belonging to the European Christian tradition, lead with the “Christian quarter” and then more briefly devote a few paragraphs to the other sections of the city, presumed to be less interesting to their readers.

At times, instead of starting with locales, the city is introduced in terms of its “communities,” roughly portrayed on the sole basis of religion (“the Christians,” “the Muslims,” “the Jews”). Whether referred to as “quarters” or “sectors” or “communities,” the vocabulary is that of a city divided and compartmentalized into a certain number of “zones” with impermeable boundaries. This way of describing the holy city, at the outset of most of the works devoted to the city’s history, leads immediately to a view of urban society that locks out any further questions. Even the authors most determined to include some of the gains of recent historiography end up, as if by reflex, organizing their analyses on the division of the city into crudely drawn ethno-religious communities.1

Yet the quadripartite division of Jerusalem, far from being an eternal given of the city’s geography, is a relatively late cartographic invention plastered on Jerusalem by European observers. Deconstructing this simplistic view is thus a necessary preliminary to analysis. If we accept these categories as a framework of understanding, it becomes impossible to account for the complexity of the issues that crisscross the history of the holy city.2 To gain a better understanding of the sites, we must first clear the ground of landmines by unearthing the simplistic, yet tenacious, markers set, ever since the nineteenth century, by Western pilgrims and explorers ignorant of local realities. This process of deconstruction is crucial in a city of pilgrimage and tourism that does not really belong to itself, or rather that belongs to temporary visitors as much as to its permanent residents. Jerusalem is as much a city of “ink and paper” as of flesh and stone—a “textual” city crisscrossed by texts and intertexts, as probably all cities are, but infinitely more so because of its central position in the imagination of monotheistic religions.

EXTERNAL BOUNDARIES, INTERNAL FRACTURES

We may begin by emphasizing how the vision of a city divided into four hermetic sections prevents us from seeing the fracture lines within each of these supposed “communities.” Confrontations during the nineteenth century that set Eastern against Western Jews, secular against religious Jews, Jews native to Jerusalem or Palestine against immigrant Jews—confrontations that go a long way to explain the internal dynamics of the Jewish inhabitants of Jerusalem—were erased for the benefit of an artificial vision of a “community” assumed to be united or unified. Place names locally used at the end of the nineteenth century in some neighborhoods said to be Jewish, such as Haret el-Halabiyya (Allepine quarter) or Haret el-Bukharriya (Bukharan quarter), already provide clues to these internal differences. The same goes for the supposed “Christian community”—a disparate collection of Greek and Russian Orthodox; Copts; Jacobite Syrians; Roman Catholics and Greek Uniate Catholics; German, English, and North American Protestants; and Ethiopians, Maronites, and Melkites, to mention only the main categories distinguishing the different houses of worship of Christianity, which at times confronted each other physically within the very walls of the sanctuary they claimed to be common to all, the Holy Sepulcher.

The community called “Muslim” was just as varied, being divided between the two main historical branches of Islam: the Sunni (who were the majority in Palestine) and the Shiites, with the addition of Ismaelis and Druzes (the latter a Middle Eastern variant of the former), whose presence in Palestine for a long time had major consequences in political and geopolitical terms. In the old city of Jerusalem, local toponyms such as Haret el-Masharqa (Easterners’ quarter) in the northeast, Haret el-Magharba (Maghrebians’ quarter) in the south, or Haret es-Saltin (quarter of the inhabitants of the city of Salt), also in the south, testify to the geographic origins of the different Muslim groups of the city and reveal the cultural and ethnic diversity among Jerusalem’s Muslims, and how much that diversity is still a part of the collective memory of the inhabitants themselves.

These internal fractures within communities are familiar to most researchers, and have long been the subject of numerous and accessible studies. They are even brought up in works about Jerusalem, as an aside to a narrative or a folkloric description. Yet, while this should prevent the artificial blending of such disparate entities, the old city of Jerusalem still keeps on being cut up into four rectilinear and homogeneous communities, offered to readers at the expense of common sense. Even though deconstructing this essentialist cartography should be the first task of conscientious historians, so many of them, out of laziness, imitation, or, more rarely, sheer ignorance, keep on reproducing ad nauseam the same vulgarized version. In so doing they contribute to the continuing existence of this simplistic schema and share in the responsibility of solidifying the barriers said at present to be unbreachable between those supposed communities.3

LANGUAGE, CITIZENSHIP, PROPERTY: SOME USEFUL CONCEPTS

Before embarking on this necessary deconstruction, we may emphasize here and now that alternative categories can be mustered to provide a view closer to the lived reality of Jerusalem’s inhabitants at the end of the nineteenth century. For instance, we can highlight the linguistic relationships among urban dwellers of Arabic language and culture, by grouping together Muslim and Christian Arabs, and, at least until World War I, certain Jews of Arabic culture and language.4

In addition to linguistic relationships, the geographic and cultural origins of the inhabitants also come into play. For instance, we may distinguish natives of Jerusalem (Jewish, Christian, and Muslim) from recent immigrants, who represent, after all, a category commonly used in Europe, both in the past and today. By doing so, we can bring to the fore legal distinctions that determined access to Ottoman citizenship, and hence property rights, voting rights, and military conscription. In the same way, we can start to perceive some affinities and porosities, which certain consulates had begun to make use of by the end of the nineteenth century: for example, between Russian Orthodox Christian immigrants and Russian Jewish immigrants; or between English Jewish immigrants and Anglican missionaries; between Jewish and Christian (mainly Baptist and millennialist) immigrants from the United States; and finally, between some important families of Lebanese, Syrian, or Jordanian origins, whether Muslim, Christian, or Jewish.

Also relevant are some robust socioeconomic categories used by social scientists, such as access to real property ownership, which, from the 1860s on, was no longer directly linked to individual religious affiliation, but remained tied to Ottoman citizenship until the mid-1870s. Here we would need to stress the crucial legal distinction between Ottoman citizens, regardless of their religion, who had access to real estate ownership and the vote, and noncitizens, who were denied such access.5 In the context of a city subject to heavy immigration, categorization in terms of nationality and the figures that can be derived from this are useful in helping us understand, for example, why Greek Orthodox Christians, who had been Ottoman citizens for centuries, were able to build power based on extensive real property ownership, from which they still benefit today, while other Christian inhabitants of the city were for centuries prevented from owning real property in Palestine and in Jerusalem. These same legal categories help us understand the lack of balance between the overall population and the body of voters, and grasp the reasons for the lower representation in municipal institutions of the more recent Jewish and Christian arrivals at the end of the nineteenth century.

Finally, there are the broader distinctions, familiar to social and urban historians, between the rich and the poor, between secular and religious, between artisans and intellectuals, and of course between the inhabitants of the old walled city who did not have to pay property taxes and the inhabitants of the suburbs who did (although the latter were sometimes free of them in certain situations). To really understand the history of Jerusalem, especially in the years around 1900, we must mobilize all these categories, which internally crosscut the artificially constructed divisions between three or four hastily labeled “religious communities.” The mere mention of some of those criteria of internal differentiation within each of the three great monotheistic religions shows that the list of the “four quarters” of the holy city is at best approximate and at worst totally false, for it masks the social reality of the urban community of Jerusalem around the turn of the twentieth century. It obviously reassures present-day readers, as it corresponds to the present system of categorization, but it typically stems from anachronic analyses. Pasting a present-day schema onto a past situation prevents us from grasping the singularity of a given historical context.6

INSIDE AND OUTSIDE CITY WALLS

Before embarking on the history of the recent four-way labeling of the old city, we must focus on the primary demographic change of the late nineteenth century in Jerusalem: the expansion outside the walls. If there is one incontestable fact about the years from 1880 to 1910, it is the phenomenon of new construction outside the walled city, which had multiple and long-term consequences: for taxation and electoral participation, but also on the symbolic and socio-economic planes, and even for city planning, given the many technical challenges posed by this new city. The causes of the building of this new city were simply demographic. The holy city—which had numbered 10,000 inhabitants in 1800, about 15,000 in 1850, and a bit more than 20,000 in 1870—grew to some 45,000 inhabitants in 1890 and to 70,000 on the eve of World War I.7 The population that increased sevenfold over barely more than a century very soon could no longer fit inside the old city, which measured only 1,000 meters by 800 meters, scarcely one square kilometer.

Between 1880 and 1900 the new city of Jerusalem was born and grew up outside the walls, and in less than twenty years it came to hold half the total population. By the end of the 1880s the mission...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- List of Maps and Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Translators’ Note

- Introduction: The Year 1900, the Age of Possibilities

- 1. The Underside of Maps: One City or Four Quarters?

- 2. Origins of the City as Museum

- 3. Still-Undetermined Holy Sites

- 4. The Scale of the Empire

- 5. The Municipal Revolution

- 6. The Wild Revolutionary Days of 1908

- 7. Intersecting Identities

- Conclusion: The Bifurcation of Time

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Jerusalem 1900 by Vincent Lemire, Catherine Tihanyi, Lys Ann Weiss, Catherine Tihanyi,Lys Ann Weiss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.