- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Building the American Republic combines centuries of perspectives and voices into a fluid narrative of the United States. Throughout their respective volumes, Harry L. Watson and Jane Dailey take care to integrate varied scholarly perspectives and work to engage a diverse readership by addressing what we all share: membership in a democratic republic, with joint claims on its self-governing tradition. It will be one of the first peer-reviewed American history textbooks to be offered completely free in digital form. Visit buildingtheamericanrepublic.org for more information.

The American nation came apart in a violent civil war less than a century after ratification of the Constitution. When it was reborn five years later, both the republic and its Constitution were transformed. Volume 2 opens as America struggles to regain its footing, reeling from a presidential assassination and facing massive economic growth, rapid demographic change, and combustive politics.

The next century and a half saw the United States enter and then dominate the world stage, even as the country struggled to live up to its own principles of liberty, justice, and equality. Volume 2 of Building the American Republic takes the reader from the Gilded Age to the present, as the nation becomes an imperial power, rethinks the Constitution, witnesses the rise of powerful new technologies, and navigates an always-shifting cultural landscape shaped by an increasingly diverse population. Ending with the 2016 election, this volume provides a needed reminder that the future of the American republic depends on a citizenry that understands—and can learn from—its history.

The American nation came apart in a violent civil war less than a century after ratification of the Constitution. When it was reborn five years later, both the republic and its Constitution were transformed. Volume 2 opens as America struggles to regain its footing, reeling from a presidential assassination and facing massive economic growth, rapid demographic change, and combustive politics.

The next century and a half saw the United States enter and then dominate the world stage, even as the country struggled to live up to its own principles of liberty, justice, and equality. Volume 2 of Building the American Republic takes the reader from the Gilded Age to the present, as the nation becomes an imperial power, rethinks the Constitution, witnesses the rise of powerful new technologies, and navigates an always-shifting cultural landscape shaped by an increasingly diverse population. Ending with the 2016 election, this volume provides a needed reminder that the future of the American republic depends on a citizenry that understands—and can learn from—its history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Building the American Republic, Volume 2 by Jane Dailey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2018Print ISBN

9780226300825, 9780226300795eBook ISBN

9780226300962Chapter 1

Incorporation, 1877–1900

On July 2, 1881, the 20th president of the United States, James A. Garfield, was shot in the back as he walked through a railway station in Washington, DC. His deranged assassin, Charles Guiteau, is frequently described as a “disgruntled office-seeker,” and indeed he was: Guiteau considered himself responsible for Garfield’s election and demanded repeatedly to be appointed consul to Paris. The stricken president lingered through the summer heat, suffering from infection, blood poisoning, and pneumonia. He succumbed to a massive heart attack on September 19, 1881.

Garfield’s death was deeply disturbing to a nation still governed by the Civil War generation. Poet Walt Whitman, who had spent the war caring for wounded soldiers, captured the apprehension occasioned by the second presidential assassination in fewer than 20 years. Of the tolling bells that announced “the sudden death-news everywhere,” Whitman wrote

The slumberers rouse, the rapport of the People,

(Full well they know that message in the darkness,

Full well return, respond within their breasts, their brains, the sad reverberations,)

The passionate toll and clang—city to city, joining, sounding, passing,

Those heart-beats of a Nation in the night.

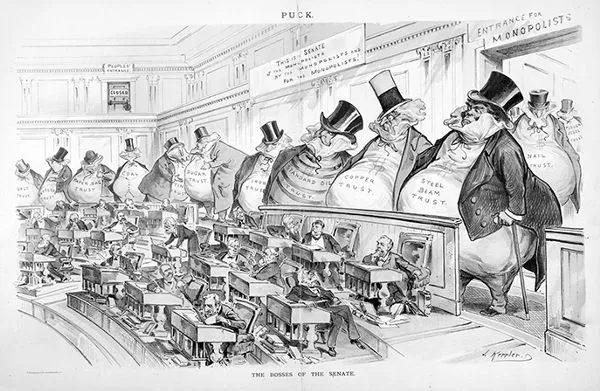

Figure 1. The Bosses of the Senate, by J. Ottmann Lith. Co., after Joseph Keppler, published in Puck, January 23, 1889. Courtesy of the United States Senate, catalog no. 38.00392.001.

Americans who had lived through the Civil War were not easily rattled. They pulled up roots and settled the continent their fathers had claimed but never truly conquered. They endured colossal loss of life to achieve monumental feats of engineering such as the transcontinental railroad and the Brooklyn Bridge. They adapted to shifting, even convulsive, economic conditions, spurred by a deluge of inventions (like electricity). They tolerated if not necessarily celebrated the strange languages and customs tucked away in the bags of millions of newcomers to the nation’s shores.

What did frighten many Americans was anything that undermined the fragile mutual understanding—the rapport—of the people. This was especially true of future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., one of the most influential American thinkers of his (or any other) time. Holmes saw the worst of the worst during his three years with the 20th Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, which suffered more battle deaths than all but four Union regiments. Wounded three times himself, Holmes survived, but the war convinced him that certitude is dangerous, and that only democracy can prevent competing conceptions of how to live from overheating and leading to violence. Whereas some—for example, white supremacists and opponents of woman suffrage—worried that expanded access to democracy would destroy American civilization, Holmes was convinced that the only way to preserve the Republic, restored through the sacrifice of millions, was to make sure that the political playing field was as accessible and even as possible. Everyone must have a say.

For Holmes, participatory government—government of the people, by the people, and for the people, as Lincoln had put it at Gettysburg—was the Republic, not a means to it. Lose one and the other disappears. The fundamental unity of the people was maintained through the democratic process. Threats to that process, whether violence, corruption, unchecked power, overbearing wealth, or disenfranchisement, endangered that sense of unity. Holmes understood that today’s losers have to believe that victory is possible tomorrow. Loss of faith in the system imperils the Republic itself.

A higher percentage of eligible voters participated in American politics during the last third of the nineteenth century than any time before or since. In presidential election years, turnout averaged 78 percent, and this takes into account the suppression of black and white Republicans by white supremacists in the South. Voters perceived fundamental differences between the two political parties. Democrats, dominated by their southern wing, argued for the rights of the states against an ever-expanding federal government. Republicans, empowered by the war and Reconstruction, embarked on a 40-year crusade of nation-building. The future of that nation depended, in great measure, on the capacity of the American political system to absorb newcomers—African Americans, immigrants, women—into the political system, and keep the peace.

In Motion

During the last third of the nineteenth century, the United States underwent a rapid and profound economic revolution. This economic transformation was rooted in abundant natural resources (e.g., land, lumber, coal, and oil), an expanding market linked by new transportation and communications networks (railroads and telegraphs), a brimming pool of labor constantly restocked from abroad, new forms of business organization that facilitated both economic growth and contraction, and a strong federal government determined to incorporate into the nation the territory (if not necessarily the indigenous peoples) of the great American West.

Iron Horses

The importance of railroads to late nineteenth-century American history cannot be overstated. US railroad mileage tripled between 1860 and 1880, and tripled again by 1920, opening vast western expanses to commercial farming, facilitating a boom in coal and steel production, and creating a truly national market for manufactured goods and staples like beef and grain. Railroad cars transported the army that “pacified” the Indians, and then unloaded the settlers who organized and incorporated the West into the nation. No models of efficiency or rationality themselves, railroads nonetheless created the conditions that allowed other industries such as steel, grain, and meat-packing to incorporate and innovate a new capitalist logic. Railroads came to symbolize American progress. In his book Triumphant Democracy (1886), steel magnate Andrew Carnegie declared, “The old nations of the earth creep on at a snail’s pace; the Republic thunders past with the rush of the express.”

Railroads changed everything they touched, beginning with space. The transcontinental railroads effected a massive spatial turn: the axis of North America, which had previously run North–South, was turned East–West. Railroads altered people’s sense of time and space. Because people experience distance in terms of time, linked by rail, places grew closer together: what German philosopher Karl Marx called “the annihilation of space by time.” It took less time in 1880 to travel from Boston to Montana (a distance of circa 2,000 miles) than to Charleston (a mere 1,017 miles). Together, railroads and telegraph systems, whose lines were strung alongside tracks, “shrank the whole perceptual universe of North America.”

Beyond people’s understandings of time and space, railroads reorganized time itself. Before 1883, clocks were set locally according to the sun. Noon was the moment when the sun stood highest in the midday sky, which varied according to longitude. When clocks read noon in Chicago, it was 11:50 a.m. in St. Louis, 11:27 a.m. in Omaha, and 12:18 p.m. in Detroit. Two trains running on the same tracks at the same moment but with clocks reading different times could find themselves suddenly occupying the same space, with deadly consequences. In November 1883, the railroad companies carved the continent into four “standard” time zones, in each of which clocks would be set to exactly the same time. Not that this meant the trains ran on time. As one rider complained, the train “was seldom there when the schedule said it would be, but occasionally it was, and [people] were amazed and angry when they missed it.”

Railroads even liberated people from weather. When the Great Lakes were frozen and nothing could move by ship, the railroads ran. As one railroad promoter announced, “It is against the policy of Americans to remain locked up by ice one half of the year.” Railroads allowed an entrepreneurial butcher named Gustavus Swift to “store the winter” by transporting ice, a large-bulk, low-value commodity, to the stockyards in Chicago, where meat-packers used it to create refrigerated boxcars, which enabled them to ship beef and pork in all directions.

By the 1890s, five transcontinental rail lines linked western mines, ranches, farms, and forests with eastern markets. The South, which laid track even faster than the rest of the nation, became integrated into this national market economy. With the trains came towns. Previously dominated by plantations, the southern landscape was dotted with villages, whose numbers doubled between 1870 and 1880, and then doubled again by 1900.

“Vast, Trackless Spaces”: The Trans-Mississippi West

What Walt Whitman referred to as the “vast, trackless spaces” of the Trans-Mississippi West was first an extension of the Mexican North. The expansive territory that became the American West was nearly all acquired from Mexico in 1848: California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Colorado, and Utah. Many people were included in this transfer, among them several major Indian nations, including the Papago, Navajo, Puebloan, and Apache, as well as approximately 75,000 Mexicans. The frontier experience of the American West was never an encounter with virgin land. It was, instead, a process in which new wilderness zones were created in places where civilizations had once existed.

At first, Indians remained in their homelands. Americans were quickly incorporated into the extensive Indian agricultural and trading networks that characterized the southwestern United States. For example, the Pima and Papago “River People” who dwelt along the Gila and San Pedro Rivers supplied the US Army with a million pounds of wheat in 1862, plus cotton, sugar, melons, beans, corn, and dried pumpkins.

In 1869, Congress created the Board of Indian Commissioners, which was composed of prominent evangelicals and humanitarians, including old abolitionists, to oversee what President Ulysses S. Grant and others termed the nation’s “Indian problem.” The commission recommended replacing the treaty system, which had treated Indian tribes as akin to sovereign nations, with a new legal status for “uncivilized Indians” as “wards of the government.”

In a departure from the prior policy of Indian removal en masse to another location, the commission recommended the creation of reservations located far from ancestral lands as well as other population centers. The goal was to isolate Indians from outside influences. Under this plan, missionaries were in charge of Indian life. They replaced Indian languages, practices, and religion with English, American models of domestic agriculture, and Christianity. They sent Indian children away to boarding school. In addition to supplanting native cultural practices, the reservation arrangement also undercut the ability of Indians to sustain themselves through trade or employment off the reservation.

What was called the “Peace Policy” was welcomed with hostility by many Indian nations. War with the Apaches broke out in Arizona. In the Great Plains and on the West Coast, the US Army battled the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Modoc Indians. President Grant remained unperturbed. In his opinion, Indians—even the warlike Apaches—could “be civilized and made friends of the republic.”

Republicans considered tribal sovereignty incompatible with the national unity forged in the Civil War. In 1871, Congress stopped negotiating new treaties with Indians and refused to recognize the independent nation status of tribes. Under the terms of the 1887 Dawes General Allotment Plan, Indians were required to distribute communal land among individual families. Those who cooperated became US citizens. So-called surplus land was sold to whites.

Indians held 138 million acres in 1887. During the following 47 years, 60 million acres were declared to be “surplus.” All told, nearly two-thirds of tribal land was conveyed to Americans through a variety of devices. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Francis Amasa Walker, the government’s guardian for the native peoples, declared in 1872, “The westward course of population is neither to be denied nor delayed for the sake of the Indians. They must yield or perish.” Most tribes did both.

Manifest Destiny

Americans settled more land between 1870 and 1900 than in all their previous history. The population of the territory to the west of Illinois and Missouri mushroomed from 300,000 in 1860 to 5 million in 1900. Much desirable land was beyond the reach of homesteaders, however. Enormous grants of public land to subsidize railroad construction, the distribution of land to Union veterans, and the use of dummy corporations allowed speculators (who acquired land not for its use but for its resale value in a rising market) and mining, timber, and cattle companies to acquire land under falsified claims. Under the terms of the Railway Act of 1864, railroad companies received 12,800 acres of public land for every mile of track they laid. This land could serve as security for bonds, or be sold to settlers, who paid for land their government had given away to the railroads.

Article 3 of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 stipulated that “the utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent.” Americans never lived up to this ideal. Instead, they negotiated treaties that pushed Indians westward, broke those treaties to expand farther, and killed Indians who resisted. Sometimes white settlers wanted Indian land to farm. Other times, they coveted water or right-of-way (in the case of railroads) or minerals. In California, white settlers fought a genocidal campaign against the native peoples there. Of some 150,000 Indians in California when gold was discovered there in 1848, only 30,000 remained by 1860.

With Native American control weakened in the West, settlers poured into the vast central plains. European immigrants, particularly Scandinavians and Germans, established themselves in the northern territories of Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakotas. During the period of mass immigration, one out of every two western settlers was foreign-born.

American-born settlers also set out across the continent, including large numbers of white and black southerners. Many rural blacks migrated west to Kansas, Indiana, and Oklahoma, where land was plentiful and cheap. “The Negro exodus now amounts to a stampede,” exclaimed one North Carolina white in 1890. African Americans also gravitated toward industry, particularly mining. “It was easy,” one miner recalled. “All you needed was a pair of gloves, overalls and experience and you could get hired anywhere.” The West had another advantage over the South: as one settler wrote to a friend in Louisiana, “They do not kill Negroes here for voting.”

Mass influx of settlers from the South and East provoked conflict with Indian nations, some of whom defended their land fiercely and resisted relocation to reservations. In 1876, during the Sioux Wars, Cheyenne and Lakota warriors defeated an overconfident Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, killing him and all his men at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

In the midst of a serious drought in 1889, Congress cut food aid to several Indian nations, including the Lakota. Deaths from hunger and disease rose on the reservations. Instead of an armed uprising, starving Native Americans turned to the Ghost Dance, a spiritual movement associated with the teachings of the Northern Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka. The circle dance of the Ghost Dance represented a broad credo of working the land, Anglo education, and, above all, nonviolence.

In 1890, the US Army massacred more than 150 Lakota, mainly women and children, at Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota. Some of the Lakota at Wounded Knee were among those who had routed George Custer at Little Bighorn. The massacre has been associated with the Ghost Dance, but in fact was unrelated. The Ghost Dance continued into the twentieth century, practiced by Indians across the country.

Immigration, Migration, and Urbanization

The population of the United States quadrupled in the half century following the Civil War. High birth rates and wave after wave of immigrants pushed the population to more than 75 million by 1900, leaving America the second-most populous nation in the world.

Immigrants gambling on the wonders of America flooded embarkation centers in New York, Galveston, and San Francisco. Some were pulled by the prospect of a higher standard of living. Others were pushed by one or more of several factors, including political oppression, religious persecution, war, and interethnic rivalries. Still others were simply trying to escape overbearing parents. Between 1879 and 1915, 25 million immigrants arrived “yearning to breathe free,” in the words inscribed on the Statue of Liberty. By then, immigrants made up nearly 15 percent of the American population.

Although some immigrants joined the stream of western settlement, most gravitated to the jobs, educational opportunities, and ethnic communities of urban America. In a relatively brief period, America’s population shifted from one with predominantly British (including Scots and Irish) and German roots to a much more heterogeneous mix. Over half of the 3.5 million immigrants who entered the United States in the 1890s came from Italy and the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires of central and eastern Europe. The vast majority of them were Catholic. However, hundreds of thousands were Jews, the first major influx of non-Christian immigrants to the United States.

Increasingly “exotic” immigrants and their American-born children constituted a majority in the nation’s largest cities—a fact that worried many native-born Americans. Some charged that immigration diluted American society by allowing “inferior” races to outnumber the Anglo-Saxons. New immigrants, wrote Commissioner of Indian Affairs Francis Amasa Walker in 1880, were “beaten men from beaten races.”

One immigrant group concerned white Americans more than any other: the Chinese. The first federal legislation designed to discourage immigration was the Page Law of 1875, which was aimed at single Chinese women on the assumption that they were prostitutes. Pressed by nativists in California, Congress passed a more comprehensive law in 1882 that banned further immigration of Chinese laborers...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 · Incorporation, 1877–1900

- 2 · Interconnected, 1898–1914

- 3 · War, 1914–1924

- 4 · Vertigo, 1920–1928

- 5 · Depression, 1928–1938

- 6 · Assertion, 1938–1946

- 7 · Containment, 1946–1953

- 8 · At Odds, 1954–1965

- 9 · Riven, 1965–1968

- 10 · Breakdown, 1968–1974

- 11 · Right, 1974–1989

- 12 · Vulnerable, 1989–2001

- 13 · Forward, 2001–2016

- Acknowledgments

- For Further Reading

- Index