![]()

1

HAMLET

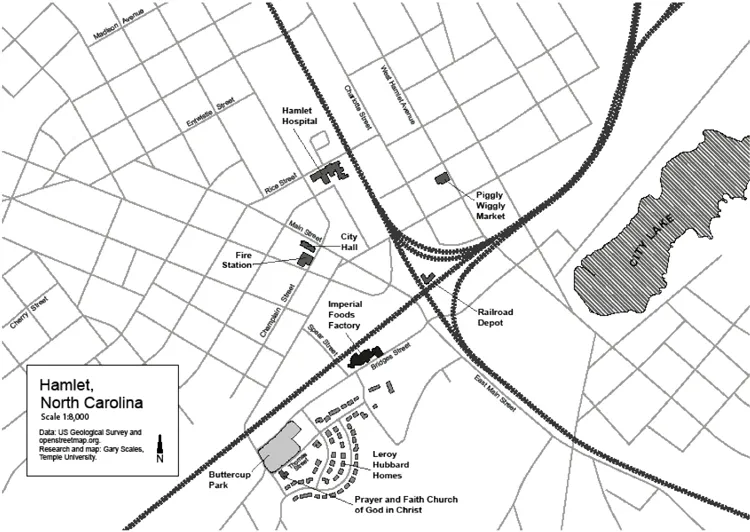

The Mello-Buttercup Ice Cream factory, with its red brick exterior and clean white tile walls inside, stood on a slightly raised plateau just up the street from Hamlet’s rounded, Queen Anne–style train depot. Everything in Hamlet was close to the railroad station. Main Street. The “black” stores on Hamlet Avenue. The NAACP headquarters. The sprawling houses with tall white columns and wide front steps. The public housing project without air-conditioning. The limestone churches with steeples that reached higher into the sky than any other building in town and the cinder-block churches no bigger than a grade school classroom. Hamlet Hospital. The Piggly Wiggly. The mini-mart that doubled as a drug corner. The movie theater that once had a crow’s nest where black people sat. The florist shops and hardware stores. The playgrounds and sports fields. The dance clubs and juke joints. The fire station and police department headquarters. The elementary schools and middle schools. The library and City Hall. They were all close to the station. Everything was close together in Hamlet because Hamlet wasn’t that big, less than five square miles, and home to 4,700 people in 1980, when Emmett Roe first came to town. But everything was close to the station because just about every house, place of worship, and business was there because of the railroad. That included the ice cream plant.

Hamlet residents will tell you that there wouldn’t have been a Hamlet without the railroad. Founded in 1873 at the junction where the Wilmington, Charlotte & Rutherford Railroad met the Raleigh and Augusta Air Line Railroad, the town didn’t welcome its hundredth resident until almost twenty years later.1 In those early days, Hamlet was known as a frontier town. Not quite the Wild West, it was still a place where card playing and whiskey drinking took place out in the open and no one said anything. By 1897, Hamlet was officially incorporated and sobered up enough that the highly capitalized and economically powerful Seaboard Air Line Railroad, known as the “South’s Progressive Railway” and “The Route of Courteous Service,” moved its regional headquarters to town. After that, Hamlet took off. By 1910, it had a Coca-Cola bottling company, five dry goods stores, and two five-and-dimes. Its population had jumped from 639 in 1900 to more than 4,000 in 1930. By then, the town had become the kind of place people moved to to get a good job and build a good life.2

“Well,” Riley Watson, a longtime foreman on the line, remarked, “if it hadn’t been for the Seaboard, Hamlet wouldn’t ever have been what it is. If they hadn’t built that railroad through here, and they hadn’t decided to make this a big division point, Hamlet … might have been a crossroad, that’s all.”3

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, with Seaboard pouring money into the town, Hamlet grew into a bustling and busy transportation hub. By the end of World War I, more than thirty trains rumbled in and out of town every day. The grinding of brakes and the whistle of locomotives woke people up in the morning and put them to sleep at night. North of the depot, Seaboard built an extensive maintenance shop, then a mammoth roundhouse, and, after that, an expansive shipping yard. Following World War II, the railroad company invested $11 million in a classification yard, the first in the Southeast, where engines, freight cars, and dining cars were pulled apart and reassembled for the next leg of their journey. Eventually, seventy-two separate tracks crisscrossed Hamlet and the edges of town. Most of the trains coming through were freight trains, pulling boxcar after boxcar loaded with shirts made in Passaic, New Jersey, on their way to Atlanta’s downtown department stores or coal from West Virginia headed to the port of Wilmington or timber from South Georgia destined for the furniture factories in High Point, North Carolina. But it wasn’t just cargo that came through. With tourism and leisure travel on the rise in America in the years after the Civil War, Hamlet became part of a new, and by far less contentious, Mason-Dixon Line, separating New York in the cold months of winter from the sunshine of Florida. Every morning, the Orange Blossom Special pulled into the depot. Late in the afternoon it was the Silver Meteor. In between, the Boll Weevil, a local running from Hamlet to Wilmington, with stops in Laurel Hill, Old Hundred, and Laurinburg, passed through the station as well.4

Four thousand people—really four thousand men, mostly white men—worked for the railroad. With a virtual monopoly on moving goods across America, railroad companies and the stout robber barons who owned them piled up mountains of profits between 1877 and 1925. The conductors, engineers, and brakemen who ran the trains and maintained the tracks got a share of the wealth as well. The railroads provided their laborers with good, steady, well-paying jobs supplemented with sick pay, unemployment benefits, and pension plans. The work could be grueling and dangerous, but the companies usually abided by safety rules and put in place protections that limited risks and injuries. A job with the railroad was by far the best job a man without a college degree or a family name could get in the piney and gently rolling Sandhill sections of North Carolina that surrounded Hamlet. These jobs were even better than having a patch of land outside of town on which to grow cotton or peaches. And they were union jobs. The men who headed the Brotherhood of Railway Carmen, the Order of Railway Conductors of America, and the nation’s other railroad unions did not, however, deliver fiery speeches about wage slavery and the destruction of capitalism at their annual meetings in Atlantic City and Chicago. They preached the gospel of bread-and-butter unionism, promising to lift their thick-necked and brawny members into the middle class. They fought for seniority protections, clearly spelled-out grievance procedures, and annual pay raises. Usually they won, in part because the railroads were making money in the first half of the twentieth century and the men who ran them wanted to avoid strikes and walk-outs.

Because the Seaboard and other railroads operated nationally, the railway unions fought for and won national wage scales. Unlike the steel and coal industries, there was little regional competition and no agreed-upon southern wage differential. A brakeman in Hamlet got paid the same amount as a brakeman in Hannibal, Missouri, or Des Moines, Iowa. That kind of money went a long way in a small southern town. It turned these men into breadwinners and guaranteed them job stability, rising living standards, and a secure retirement. When they married, as most surely did, their wives generally stayed at home, taking care of the cooking and housekeeping, volunteering at school and church, and raising children and looking after elderly neighbors.5

“Hamlet became a thriving, bustling town,” explained local journalist Clark Cox. And that prosperity, he maintained, was broadly shared. “Hamlet,” Cox wrote, “had something that (nearby) Rockingham didn’t have—a large middle class. Railroad workers were skilled, unionized, and much better paid than textile workers.”6 The money they made as conductors, engineers, foremen, and machine shop supervisors spread across the town and lifted up whole families for generations to come. Getting a job with the railroad was usually a family affair. Brother recommended brother. Fathers got apprenticeships for sons. Church members put in a good word for fellow congregants and relatives. Once a man landed a railroad job, he usually kept it for the rest of his working life.

Burnell McGirt served in the Navy during World War II. He came home and got his first and the only job he ever had with the railroad. “I hired out in May of 1946,” he told an interviewer in 2009. “I worked in the signaling department until 1971, and from there I went to the roadway department. I had thirty-eight years of service with the railroad.”7

Nat Campbell’s stint with the railroad lasted forty-two years. Over that time, he always made decent money. “I was able to give my wife and children things that I probably couldn’t give them if I worked anywhere else,” he bragged in 2009, looking back on his years as a carman and laborer in the wheel-and-axle shop. “We always had a nice trip,” he said. They had a Sears charge account, and they ran it up each year buying Christmas presents for “our young’uns.” “By November of the next year,” he joked, “we had it all paid up, and we had to start all over again.”8

Once white workers—“railroad men,” as they called themselves—got married and saved a little money, they bought modest brick houses and wood bungalows to the east of the depot on Boyd Lake Road and Spring Street, and not far from the center of town, on Cherry Street and Rosedale Lane. Seaboard accountants and managers, conductors and crew leaders, the aristocrats of labor, settled even closer to Main Street, where they lived next to the high school principal and the football coach, lawyers, and store owners on shaded streets with names like Madison and Hamilton, Entwistle, and Pineland, in white clapboard houses with lawns as manicured as country club greens and porches wide enough for three-person bench swings. In the spring, these thoroughfares smelled like azaleas and dogwoods, and in the fall like damp pine needles and moist oak leaves. Kids tracked along the sidewalks, trick-or-treating at Halloween and singing carols at Christmas. In the years after World War II, some railway workers moved their families farther out onto curvy streets in small subdivisions named after plantations, into what passed for Hamlet’s suburbs. They parked their motorized fishing boats on trailers out front in their driveways next to their new Ford trucks, Buick sedans, and Chevy station wagons. In the backyards were brick grills and above-ground pools. In fact, one local official chuckled about Hamlet, “We had more backyard swimming pools then Beverly Hills. It was a high-income place for the South.”9

Most of Hamlet’s prosperity stayed on the white side of the town’s racial divide. Thirty-nine percent of Hamlet residents in 1980 were, according to the United States Census, African American. But not many held the kinds of high-paying jobs that pulled them out to the suburbs or paid for backyard pools. On average, African Americans made almost 40 percent less than whites, and they were less likely to work on the railroads, which classified jobs along racial lines well past World War II.10 By the time that Imperial Food Products began to relocate to Hamlet from northeast Pennsylvania, twenty-six years after the Brown decision, jobs were no longer explicitly segregated, the lights were off on the minstrel shows that used to play at the city ballpark, voting booths were open to everyone, and local children attended integrated schools. But when the bell rang after the last class period, the African American students still went home to largely segregated neighborhoods; they still knew that some sections of town were essentially off-limits to them and most still had little faith that the police would protect them or their property. Sunday remained the holiest and most segregated day of the week, as black families went to black churches and white families went to white churches.11

Yet within Hamlet’s black community there was, as one local preacher noted, an “economic divide.” Along Charlotte Street, a short walk from the depot, African Americans “who were doing well,” doctors and teachers and families with men who worked for the railroads as porters and waiters—and later on, as employment segregation broke down somewhat, as switchmen, machinists, and mechanics—lived in tidy houses with neat stone walkways and flower-filled window boxes. By 1970, a handful of black professionals had moved away from the Main Street area into one of the neat ranch houses with aluminum carports in the tiny black suburban development known as McEachern Forest on the southern edge of town, named after a successful Hamlet African American undertaker, businessman, and politician who himself lived there.12

African Americans who taught in the schools, worked as janitors in the hospital, and held decent railway jobs lived in simple brick homes just north of Hamlet Avenue along Pine, Washington, and Monroe Streets. Men who worked the dirtier, but still steady, jobs loading coal, hauling freight, hammering rails, and washing down engines lived to the south of downtown near Bridges Street, and even farther south and north, in narrow trailers, on lots cut out from forests of tall, skinny pine trees.13 Their neighbors washed dishes at local hotels, stocked the shelves at hardware and auto parts stores, and cleaned up around the depot and the filling stations. They hauled wood and made a little extra money picking peaches and cotton during the harvest seasons. Black women—like Imperial worker Loretta Goodwin and John Coltrane’s mom—no matter where they lived, including along Charlotte Street, contributed to their household incomes by waiting tables, picking crops, and, mostly before 1980, cleaning toilets, folding clothes, and cooking dinner in the homes of white railroad workers, doctors, lawyers, and firefighters.

Many of Hamlet’s African American families didn’t actually live in Hamlet. They lived in the North Yard, an unincorporated section of Richmond County with a population of between eight hundred and one thousand people that sat about halfway between the Hamlet train depot and Seaboard’s vast maintenance facilities north of town. Some houses in this area were neat and tidy and clustered together in family plots. Most, however, were shotgun shacks and trailers owned by politically connected white landlords, men like D.L. McDonald.

Born in 1911, Daniel Leonard McDonald graduated from high school and went right to work as a carpenter. It didn’t take long before he moved up a few rungs and became a general contractor. Over the next several decades, he built hundreds of houses, from simple lakeside cabins to sprawling ranch homes across Richmond County. Between 1961 and 1978, he served on the Richmond County Board of Commissioners.14 Throughout his years of real estate and political success, McDonald held on to a North Yard general store where he extended credit to his tenants and their neighbors. Locals called him “Jot It Down” because every time someone picked up a can of beans or a loaf of bread, he wrote it down in his book. He would add it to the rent. Then, it seems, he would factor in interest and other fees. When it came time to settle up, no one in the North Yard ever seemed to be able to get all of their debts erased from D.L. McDonald’s book.

McDonald charged between $50 and $100 a month for one of his three- or four-room houses in the North Yard. Most of these tin-roofed places sat a foot or two off the ground on short stacks of cement blocks. Well into the 1960s, some still had hand-dug wells and outhouses in the back. “There were so many holes in the floor,” remembered Martin Quick of his North Yard rental house, “that if you dropped a penny you had to go outside to pick it up.” During the winter, his family shoved crumpled pieces of newspaper into the holes in the walls to keep out the cold.

Locals knew that they could find a drink and a dice game in the North Yard just about any time of day. “If my mom got word I was there,” Joseph Arnold, who lived in one of Hamlet’s black neighborhoods, chuckled, “I’d be in trouble.” Even if she didn’t know he was there, he made sure he left by nightfall.15

“I wouldn’t have gone over to that part of town,” Josh Newton recalled. There just wasn’t anything there for him, the white son of a white railroad worker who didn’t drink or smoke and was getting ready to go to college. At least, that’s how he looked at it at the time.16

When Mike Quick’s family moved from the North Yard to the Leroy Hubbard Homes, the South Hamlet public housing project down the hill from the Mello-Buttercup factory on Bridges Street, he felt like a real-life version of the television Jeffersons, moving on up the social ladder. For the first time in his life, the future NFL All-Pro wide receiver lived in a place where he couldn’t see the ground through the floors and his neighbors didn’t walk out the back door to go to the bathroom. But he remained in a segregated neighborhood, one where most people were just getting by, though things got better for his family when he entered the fifth grade around 1971 and his mom, the family’s breadwinner, landed a job as a nurse’s assistant at Hamlet Hospital not far from the depot and downtown.17

From the time that Seaboard set up shop in town, even the people who didn’t work for the railroad in Hamlet, black and white, still depended on the railroad. For years, Walter Bell shined shoes at the station. J.C. Niemeyer started in the Seaboard maintenance shops around the turn of the century. A few years later, in 1902, he left the railroad and opened the town’s first laundry. J.L. Dooley, a carpenter, made his living building and repairing homes for Seaboard engineers and conductors. W.R. Bosnal and Company manufactured crossties and switches. Before refrigerated cars came into use, the Hamlet Ice Company employed fifty men, making huge blocks of ice and delivering them to the yards to keep the fruit from Florida and vegetables from New Jersey cool and fresh in transit. During World War I, runners carried platters of fried chicken, potato salad, greens, and cornbread from McEachern’s Hotel, an African American–owned rooming house on Bridges Street, not far from where the Imperial plant would be, over to the depot and sold them for a quarter each to hungry black soldiers passing through town, men trusted to fight for the United States Army but not permitted to get food at the whites-only lunch counters and eateries on Hamlet’s Main Street.18

Before the wide adoption of Pullman cars in the years after World War I, passengers didn’t sleep overnight on trains. They got off at midway points between New York and Miami in places like Hamlet. Local businesses grew to meet the travel needs of these short-term visitors. Passengers in blue blazers and silk skirts stayed at Hamlet’s Terminal Hotel or at the fancier Seabo...