![]()

Foreword

Truth is everything in Sikhism, the truth of action, the truth of an individual, God’s truth. The heritage of the Sikh people is one of courage and victory over adversity. Our leaders were brave revolutionaries with the finest minds, warriors who propagated values of egalitarianism and selflessness.

But sometimes I feel imprisoned by the mythology of the Sikh diaspora. We are apparently a living, breathing success story, breeding affluence through hard work and aspiration. There is certainly much to be proud of and our achievements and struggles have been extraordinary. They are a testament to our remarkable community – energetic, focused and able. But where there are winners there must be losers. And loss.

I find myself drawn to that which is beneath the surface of triumph. All that is anonymous and quiet, raging, despairing, human, inhumane, absurd and comical. To this and to those who are not beacons of multiculturalism, who live with fear and without hope and who thrive through their own versions of anti-social behaviour. I believe it is necessary for any community to keep evaluating its progress, to connect with its pain and to its past. And thus to cultivate a sense of humility and empathy: something much needed in our angry, dog-eat-dog times.

Clearly the fallibility of human nature means that the simple Sikh principles of equality, compassion and modesty are sometimes discarded in favour of outward appearance, wealth and the quest for power. I feel that distortion in practice must be confronted and our great ideals must be restored. Moreover, only by challenging fixed ideas of correct and incorrect behaviour can institutionalised hypocrisy be broken down. Often, those who err from the norm are condemned and marginalized, regardless of right or wrong, so that the community will survive. However, such survival is only for the fittest, and the weak are sometimes seen as unfortunates whose kismet is bad. Much store is set by ritual rooted in religion – though people’s preoccupation with the external and not the internal often renders these rituals meaningless.

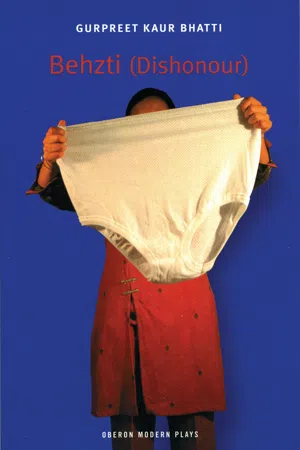

My play reflects these concerns. I believe that drama should be provocative and relevant. I wrote Behzti because I passionately oppose injustice and hypocrisy. And because writing drama allows me to create characters, stories, a world in which I, as an artist, can play and entertain and generate debate.

The writers I admire are courageous. They present their truths and dare to take risks whilst living with their fears. They tell us life is ferocious and terrifying, that we are imperfect and only when we embrace our imperfections honestly, can we have hope.

Such writers sometimes cause offence. But perhaps those who are affronted by the menace of dialogue and discussion, need to be offended.

The human spirit endures through the magic of storytelling. So let me tell you a story.

Gurpreet Bhatti

November 2004

My thanks to Janet Steel, Lindiwe Phahle, Cathy King, Roy Battersby, Michael Buffong, Amber Lone, Anne Edyvean, Manjeet Singh, Surinder Kaur Bhatti, Arun Arora, Sunil Lakhanpal, SAMPAD, everyone at The Birmingham REP and special thanks to Ben Payne.

![]()

Characters

BALBIR

MIN

ELVIS

GIANI JASWANT

MR SANDHU

TEETEE

POLLY

![]()

For Lindi, who guided me to the truth.

And who was the finest human being I have ever known.

I thank God for the gift of your soul, my beloved,

most treasured friend.

![]()

PROLOGUE

Bathing, Dressing And Eating

BALBIR KAUR, a Sikh woman in her late fifties, sits naked perched on a small stool in a bath. Her face is scarred with disappointment but her eyes are alive with ambition. There is a bucket of water and a plastic mug in front of her. She takes a mugful of water and pours it over her body. She looks around anxiously and shouts out. She speaks with a Punjabi accent.

BALBIR: No soap!

Silence. She looks around again.

No bloddy soap, shitter!

Silence. BALBIR pours another mugful of water over herself. MIN, a faithful but simple lump of lard, bustles in. She’s a sturdy but ungainly ingénue, prone to outbursts of extreme excitability. MIN is dressed unfashionably in mismatched A line skirt, patterned blouse and pink trainers. Her uncombed hair is in bunches, and she looks younger than her 33 years. She hurriedly unwraps a new bar of household soap.

MIN: It was in the flipping fridge.

BALBIR: You want me to die.

MIN: Those chipolatas smell all carbolic now… I’m at sixes and sevens…

BALBIR: Before I have finished living.

MIN: Most probably butterflies.

MIN hands BALBIR the soap and refills the bucket. MIN goes to lather BALBIR’s back and body.

BALBIR: Too ...