- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This beautifully designed, full-color textbook introduces the Roman background of the New Testament by immersing students in the life and culture of the thriving first-century towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which act as showpieces of the world into which the early Christian movement was spreading. Bruce Longenecker, a leading scholar of the ancient world of the New Testament, discusses first-century artifacts in relation to the life stories of people from the Roman world. The book includes discussion questions, maps, and 175 color photographs. Additional resources are available through Textbook eSources.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access In Stone and Story by Bruce W. Longenecker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Ancient Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One: Protocols of Engagement

1

Human Meaning in Stone and Story

Throughout history, people have told stories to help them interpret their lives within the cultures in which they were embedded. These were stories about who they were, where they came from, what’s wrong with the world, how they were connected with other people, how they were different from other people, and where things were going. The more those stories could explain their world, the more powerful they proved to be; the more powerful those stories were, the more useful they were for interpreting people’s life stories.

Earliest Christianity, even in its various forms, began to get a foothold in a world very different from our own. It told its stories in a context far removed from the twenty-first century. Appreciation for the contributions of early Christian voices to the articulation of human meaning grows when those voices are heard in relation to their own world—the Greco-Roman world of the first century. That world was animated by a tournament of narratives about the world and its supposed deities. It was in relation to that tournament that a small number of Jesus-followers began to tell stories alongside the many others that were already on offer. Arguably, if Christian stories can contribute to the quest for meaning in contexts other than the first-century world, their potential is augmented when those stories are informed by an understanding of their significance within their original context.

There are a number of ways to become immersed in that first-century world. Two standard methods for approaching the Roman world include (1) the study of ancient classical texts and (2) the study of archaeological discoveries from that ancient world. This book primarily adopts the second of these—exploring the material culture of the Roman age through the illumination provided by the archaeological site of Pompeii, with assistance from Pompeii’s sister town, Herculaneum (and at times artifacts from nearby first-century Vesuvian villas). Literature from the Roman age will be referenced occasionally, in instances when it significantly aids interpretation of the material evidence of the two Vesuvian towns.

Through these two spellbinding Vesuvian sites, the first-century configuration of Roman culture comes to life in concentrated form. No other ancient site comes close to offering the vast historical resources that the Vesuvian towns offer. Roughly 150 miles south of the bustling city of Rome, these two towns died when their local mountain, Mount Vesuvius, erupted in the year 79 CE. Volcanic debris from that eruption suffocated the Vesuvian towns, burying them under heavy blankets of volcanic pumice (in the case of Pompeii) and flows of dense pyroclastic ash (in the case of both Pompeii and Herculaneum). Now largely uncovered by archaeologists, these first-century towns sit on the doorstep of our twenty-first-century world, boldly displaying much of what life was like in two small urban contexts of the Greco-Roman world.

Figure 1.1. Two photos depicting Mount Vesuvius behind the material remains of Pompeii today

This book will offer windows into the Greco-Roman context in which Jesus-devotion was getting its initial foothold. It will do this by highlighting selected Vesuvian artifacts that best illustrate aspects of the Roman world and that, in turn, impact our understanding of early Christian texts and phenomena. Pompeii and Herculaneum were, after all, urban centers vibrantly alive at the very time that the early Jesus-movement was first getting some traction in urban centers of the Roman world. The Vesuvian remains are a treasure trove of life from two urban centers and various rural villas of the first century CE. They access that ancient world in a way that matches anything we might wish for, and they supplement the great literary texts of Greek and Latin writers with the everyday life of ordinary people who would otherwise be largely invisible to us. Moreover, Vesuvian artifacts reveal Greco-Roman contexts in an organic, interrelated fashion; the inner sinews connecting first-century urban culture are on display at Vesuvius’s base in a fashion unequalled at any other ancient site. In short, when it comes to understanding the world of the first century, no other urban site offers anything close to the Vesuvian resources of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

In addition, today there are exciting opportunities for exploring those Vesuvian towns by means of internet resources. Those opportunities allow people with curious minds to delve deeply into the Vesuvian archaeology from the window of their own digital screens, making the study of the Roman world easier than ever before. More will be said about this in chapter 3.

Figure 1.2. Map showing the location of the towns Pompeii and Herculaneum on the seacoast and in their proximity to Mount Vesuvius

Before we get too far, however, I want to highlight my motivation for writing this book by recalling the words of one of my former undergraduate students. Toward the end of a university course I had taught, I asked my students to write reflections on what they had learned about the early Christian texts in their historical context. One perceptive undergraduate included the following in her larger reflections: “I’m starting to realize that taking these [New Testament] writings and directly applying them to our modern context without thinking about the ‘interpretative bridge’ of time and culture is about as helpful as taking a scale to the moon. Weight is going to be different there, because gravity is different there!”

Much might be said in relation to this observation, but this is not the place for that. Instead, borrowing this student’s analogy, I simply note my hope that this book will help readers construct that “interpretative bridge” to the Roman world, in the enterprise of reading early Christian texts in their first historical contexts. Placing early Christian discourse in its historical setting will allow the force of that discourse to be more readily apparent. And in this task we will be assisted by those people of Pompeii and Herculaneum who will act as our guides, our “key informants” of the Roman world, even though many of them lost their lives in a horrific tragedy of unimaginable proportions.

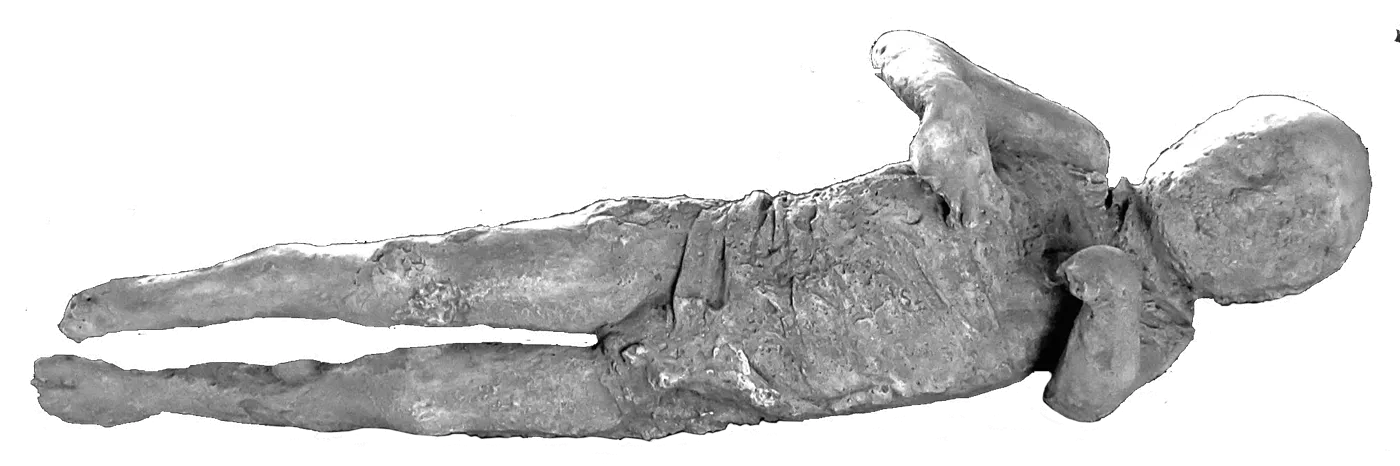

Figure 1.3. Skeletons of some of the people killed in the eruption of Vesuvius, who had sought shelter in the storage bays on the seafront at Herculaneum

A Glance at Our Guides

In this book, we will have the honor of entering into the Roman world through the lives and lifestyles of the people who populated the residences of Pompeii and Herculaneum. These people, who were often neighbors to each other, will act as our guides into a world that had at least as many differences from our own world as similarities. We will recognize many parts of their world, but at times we might also scratch our heads and wonder about other aspects. Within this very foreign world, some people had big dreams, clear schemes, and high hopes for the future, while many others must have been discouraged by the drudgery of their situations. Some of them were eager to think through the complexities of life. Some of them looked forward to the next party they would attend. Some of them expressed their hatred for their competitors. Some of them were desperately in love. Some of them were stuck in loveless marriages, and some of them were desperately bitter at the way love had treated them. These aspects of their lives, and more, are on display as we enter the spaces of the Vesuvian residents.

Figure 1.4. A plaster cast of a young child whose body decomposed in the volcanic debris (from the House of the Golden Bracelet, 6.17.42)

At times we get glimpses into their ordinary lives by means of graffiti that they left on walls throughout their towns. The Roman biographer Plutarch encouraged his readers to avoid glancing at the graffiti all around them, since those graffiti only encouraged “the practice of inquiring after things which are none of our business” (On Curiosity 520E). But “the practice of inquiring after things” like first-century graffiti is precisely the “business” of historical inquiry. Those graffiti give us access to first-century lives, revealing the everyday occurrences of ordinary people. So, for instance, out of the thousands of graffiti from the Vesuvian towns, one graffito reads: “A copper pot went missing from my shop. Anyone who returns it to me will be given 65 bronze coins [literally, sestertii]; twenty more will be given for information leading to the capture of the thief” (CIL 4.64; for an explanation of the “CIL” enumeration, see chapter 3). Some of the residents of these towns were honest and helpful, as in this graffito: “If anyone lost a mare laden with baskets on November 25, apply to Quintus Decius Hilarus, freedman of Quintus . . . at the Mamii estate on the other side of the Sarno Bridge” (CIL 4.3864).

Figure 1.5. Portraits (with damage to the right portrait) of two children (boy on the left and girl on the right) depicted on the walls of their bedroom (from Pompeii’s House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto, 5.4.a)

Many graffiti were not so courteous, as in this one directed to someone named Chios: “I hope your hemorrhoids rub together so much that they hurt worse than they ever have before!” (CIL 4.1820). Still other graffiti get to the point even more quickly: “May you be crucified” (CIL 4.2082); “Curse you” (CIL 4.1813); and “Samius to Cornelius: go hang yourself” (CIL 4.1864). In some ways, the world has not changed very much from the days when early Christianity was struggling to get a foothold within first-century society.

Nowhere is that more clear than in graffiti about love. “No young buck is complete until he has fallen in love,” one Pompeian resident advised (CIL 4.1797). Around the town, graffiti reveal that the town’s residents were often enmeshed in relationships of love. One man described his darling as the “sweetest and most lovable” girl (CIL 4.8177), while another referred to his sweetheart Noete as “my light” (CIL 4.1970). A man named Caesius declared that he “faithfully loves” his partner, whose name has not survived beyond the first letter, M (CIL 4.1812). Yet another gave a wonderful compli...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Endorsements

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Looking Ahead

- Part One: Protocols of Engagement

- Part Two: Protocols of Popular Devotion

- Part Three: Protocols of Social Prominence

- Part Four: Protocols of Household Effectiveness

- Looking Further

- Appendix: Questions to Consider

- Abbreviations

- Glossary

- Further Reading

- Credits

- Scripture and Ancient Writings Index

- Back Ad

- Back Cover