![]()

PART ONE

THE BUDDHA OF SUBURBIA

1990–1997

We are not slaying dragons any more, just cleaning up the shit they leave behind.

Edwina Currie (1991)

It’s a great responsibility bringing a child into the world. You get all those embarrassing questions, like: What’s a Labour government?

Helen Lederer (1991)

CHARLES FOX: Do you enjoy anything, Mr Pitt?

WILLIAM PITT: A balance sheet, Mr Fox. I enjoy a good balance sheet.

Alan Bennett, The Madness of King George (1994)

![]()

1

Enter John Major

‘The devil you know’

NORMAN ORMAL: I spotted the potential of John Major way before we realised he didn’t have any.

Craig Brown, Norman Ormal (1998)

ALAN PARTRIDGE: People forget that on the Titanic’s maiden voyage, there were over a thousand miles of uneventful, very pleasurable cruising, before it hit the iceberg.

Patrick Marber, Steve Coogan & Armando Iannucci, Knowing Me, Knowing You with Alan Partridge (1994)

‘I’ve always voted Labour,’ I said. ‘But . . .’ I hesitated. Suddenly the stakes had become very high. ‘But what?’ ‘But I felt secretly relieved when the Tories won.’

David Lodge, Therapy (1995)

John Major was a very young prime minister. In this, as in so little else, he was part of a trend, for the fashion, as the twentieth century progressed, was very definitely away from the older premier. In the decades either side of the Second World War, the average age of a prime minister was sixty-seven; in the years after 1960, it fell to fifty-eight before, in the 1990s, a further ten years were shaved off the figure. Much of that latter reduction was due to Tony Blair, who was often cited as the youngest prime minister of the century, being just shy of his forty-third birthday when elected in 1997. Less well remembered is the fact that the record he broke was that of his predecessor.

And perhaps it isn’t surprising that Major’s youth is so easily forgotten. He made far less play of that dubious merit than did Blair, giving the appearance of someone who had been middle-aged for some considerable time. There was too, when he became prime minister in November 1990, a higher cultural premium placed on experience than was to become the norm, and it was more important for him to emphasise his record in government, in contrast to that of the two opposition leaders – Neil Kinnock and Paddy Ashdown – though both were older than he was.

That record, however, was so compressed that it resembled a crash course in statesmanship. Major had never been in opposition, having entered Parliament in the 1979 general election that brought Margaret Thatcher to power. He had served as foreign secretary and then as chancellor of the exchequer, but these had been only brief appointments. Most of his three and a half years in the cabinet had been spent in the backroom job of chief secretary to the Treasury. Little known outside Westminster, he was far from an obvious choice to become leader of the Conservative Party.

His standing was illustrated by the media coverage that followed the political demise of Margaret Thatcher in 1990. Having been challenged in an election for the leadership of the party by her former defence secretary, Michael Heseltine, Thatcher had failed to secure sufficient votes to win on the first ballot. She was then informed by her cabinet colleagues that she stood little chance of prevailing in the next round, and announced her resignation on the morning of Thursday 22 November, thereby freeing cabinet ministers to enter the race – an opportunity immediately picked up by the chancellor, John Major, and foreign secretary Douglas Hurd. That evening, the BBC and ITV news bulletins produced graphics to illustrate how the electoral process worked; both followed the conventional wisdom of the day and showed Major coming last and being knocked out, leading to a final third-ballot showdown between the flamboyant self-made millionaire Heseltine and the patrician Old Etonian Hurd.

In the real world, to the surprise of the media, it took just four days for Major to move into Number 10, having seen off both rivals with no need for that final ballot. His opening words to his first cabinet as prime minister summed up the mood of a perplexed public: ‘Well, who’d have thought it?’

The implausibility of his rise helped create an image of accidental premiership that he never quite threw off. As prime minister, he served for longer than, say, Clement Attlee, David Lloyd George or Edward Heath, longer than James Callaghan and Neville Chamberlain put together, and just a few months shy of Harold Macmillan, yet he made less impression than any of those figures even at the time. In retrospect his premiership is remembered by many as being little more than a brief interregnum. Indeed that was the view of the Independent’s editor, Andrew Marr, even as Major was leaving office: ‘he was what happened after Margaret Thatcher and before Tony Blair.’ Others were less certain of his role. ‘I simply find myself asking: Does he really exist?’ commented the veteran MP Enoch Powell in 1991, and if that was unnecessarily cruel, it reflected a widespread perception. Satirists, used to the raw red meat of anti-Thatcher savagery, were at a loss to know how to caricature this mild, affable but seemingly bland embodiment of suburban man. Guy Jenkin, the co-creator of Channel 4’s topical sitcom Drop the Dead Donkey, recalled that ‘Trying to write jokes about John Major was like trying to write jokes about grass growing,’ and his writing partner, Andy Hamilton, agreed: ‘They were dull days for comedy writers.’ Their best joke in those early days came with the concept of a John Major-o-gram: ‘They send round a bloke in a suit. He stands here for ten minutes, no one notices him and he goes away again.’

The satirical puppet series Spitting Image reached much the same conclusion. On air at the time of the change in leadership, the programme’s first attempt to depict Major showed him with a radio antenna on his head, so that Thatcher could operate him by remote control, but when the show returned for its next series in 1991, it had devised a more enduring incarnation: a puppet sprayed all over with grey paint who had an unhealthy obsession with peas and starred in a new feature, ‘The Life of John Major – the most boring story ever told’. The greyness became the defining public image of the man so that when, in 1992, someone drew a Hitler moustache on a portrait of Thatcher in the House of Commons, Neil Kinnock could joke on Have I Got News for You: ‘Next week they’re going to colour in John Major.’ He was by common consensus dull, boring and lacking in glamour; in 1996 readers of the BBC’s Clothes Show Magazine voted him ‘the person they would least like to see in his underpants’.

Major’s voice, too, with its slightly strangled, expressionless tone and its tendency to pronounce the word ‘want’ as ‘wunt’, came in for mockery. ‘He doesn’t speak English,’ raged the irascible newsreader Henry Davenport in Drop the Dead Donkey, ‘he speaks Croydonian, an incomprehensible suburban dialect,’ while the comedian Jo Brand concluded that he ‘talks like a minor Dickens character on acid’. The view from abroad was no more encouraging. The French newspaper Le Figaro nicknamed him ‘Monsieur Ordinaire’, while even the Belgians – not universally renowned as the most vibrant and colourful people in Europe – were unimpressed: ‘In his grey Marks and Spencer suit, he is hardly a charismatic figure,’ sniffed the Brussels-based daily Le Soir.

Yet this allegedly grey man had risen to become prime minister, leader of the most successful political party in the history of democracy. Not for nothing was one of his early biographies titled The Major Enigma; there had to be more here than met the casual eye. And behind the demure demeanour, it transpired, there lurked a shrewd and effective political operator. His closest friend in the Commons, Chris Patten, was later to describe him as ‘very, very competent – the best of our political generation’, while the BBC’s political editor John Cole wrote: ‘he was more politically astute than his critics, and had run rings around them.’ Nor was his appeal confined to Westminster: in the 1992 general election Major secured for the Conservatives the largest popular vote ever recorded by a British political party, despite the supposedly widespread opinion that he was deeply uninspiring. Even with all the derision directed at him, he was, for a while, genuinely popular. ‘The public liked him,’ wrote Michael Heseltine with a truthful simplicity.

And in person he was clearly very likeable, displaying a generosity of spirit that is not always evident in politics. In January 1991 the veteran socialist Eric Heffer, now riddled with cancer, made what was clearly going to be his last ever appearance in the House of Commons to vote against Britain’s involvement in the war against Saddam Hussein. Before the debate began, Major crossed the floor of the chamber, knelt beside the dying man and had a private conversation, an emotionally charged gesture that provoked an outbreak of applause from MPs of both sides. Tony Benn, in tears at the condition of the man who was probably his closest friend at Westminster, noted in his diary: ‘I have never, in forty years, heard anyone clapping in the House of Commons. Eric was overwhelmed.’

Major was also very tactile, offering men a two-handed handshake and flirting with women to great effect, so that even political opponents were disarmed. John Prescott’s wife, Pauline, was said to have been ‘bowled over by how witty and charming he was’, while the hardened Eurosceptic Teresa Gorman was almost persuaded to abandon her rebellious inclinations and vote with her own government, as Major sat holding her hand and talking gently to her: ‘It was very seductive; I could feel myself tingling all over.’ At a dinner thrown by the Speaker of the House of Commons, Paddy Ashdown saw the prime minister chatting up Labour’s former deputy leader Margaret Beckett with a line worthy of a Carry On script: ‘Would you like a nibble of my mace?’ As Ashdown remarked, ‘He is a terrible flirt!’

Major had too a gift for personal communication when meeting the electorate that hadn’t been noted in his predecessor, though his empathy was less evident in the heated environment of the House of Commons or when delivering platform speeches. In an age that was, we were repeatedly told, dominated by television, he was adjudged by many to be a poor performer on the small screen, though some of his charm evidently came through. The journalist John Diamond attended a dinner party in 1991 at which a woman ‘listed for the amazed assembly the things she would gladly do with John Major between a pair of satin sheets’. It was, noted Diamond, the men, not the women, who were puzzled by this declaration and who demanded clarification of the prime minister’s inexplicable sex appeal.

Perhaps the issue did ultimately come down to gender. The commentators, critics and comedians of the time were predominantly male, while Major’s air of quiet self-assurance and mild coquettishness played best with female voters, many of whom had deserted the Conservative Party during Thatcher’s incumbency. ‘His polling figures, especially among women, are amazing,’ marvelled Chris Patten in 1991. The very ordinariness of the man, his decency and honesty, however mocked, was an appealing attribute and was deliberately played up. Major himself was clear that he wanted ‘to be prime minister without changing, without losing the interests that every other Briton had, without having no time for holidays, no time for sport, no time for anything but the higher things of life’. The restoration of normality was, to use a phrase often associated with him, most agreeable.

Much of this was only to emerge as Major’s premiership wore on. Certainly it was of less significance over those few days in November 1990, as Tory MPs considered who was to succeed Thatcher as their leader. Then there was just one overriding question: which of the candidates was most Thatcherite and could best protect the legacy? Loyalists, outraged at her defenestration, wished to keep the flame alive, while even some of the regicides were troubled by feelings of guilt over what they had done and sought to make amends. Their verdict rapidly became clear. ‘Most Tory backbenchers regard Mr Major as the most Thatcherite of the three contenders,’ reported The Times, ‘although it is something of a mystery why he should have acquired this reputation.’

Major’s privately expressed position was clear – ‘I’m not a Thatcherite, never have been’ – but in public that mystery remained unsolved and, for the moment at least, largely unaddressed. His campaign team for the leadership election included most of the leading right-wingers, the likes of Norman Lamont, Michael Howard, Peter Lilley and Norman Tebbit, while his victory was greeted rapturously by Thatcher herself. ‘It’s everything I’ve dreamt of for such a long time,’ she said, as she embraced Major’s wife, Norma, on the night of his triumph; ‘the future is assured.’ Within a year, Thatcher was telling her friend, the journalist Woodrow Wyatt, that ‘I think he has deceived me,’ and although the truth was rather that she had deceived herself, her sense of betrayal was shared by many on the right of the party, contributing heavily to the disloyalty that became increasingly prevalent amongst Conservative MPs in the 1990s.

As chancellor, Major had taken Britain into the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), tying the value of sterling to that of the deutschmark. Given that record, how could the Eurosceptic supporters of Thatcher have persuaded themselves that he was on their side? Part of the answer was his demonstrable dryness in economic matters. His espousal of the ERM was based on counter-inflationary concerns, rather than any great enthusiasm for the European project, and his one well-known quote as chancellor, as the country slid into recession, was to urge resolution in the fight against inflation: ‘If it isn’t hurting, it isn’t working.’ Beyond that, there was a studied refusal to reveal anything much about his own political beliefs. He was associated with no particular faction in the party, had written no influential papers for think tanks, delivered no speeches that anyone had noticed, appeared at not a single press conference during the 1987 election campaign.

Many years later, when he was in opposition, Major was asked by a colleague, Michael Spicer, where he had really stood on the great European questions that had dominated his premiership. ‘He smiles and makes no audible response,’ wrote Spicer in his diary. ‘I suppose that is how he became prime minister in the first place.’ Others had spotted this characteristic earlier. ‘His whole life,’ noted the Tory MP Edwina Currie, his former lover who knew him better than most, ‘has the waft of an opportunistic silence reflecting tremendous self-discipline.’

Equally important to his image as a Thatcherite, however, was a simple cultural perception of his humble origins. His father was a trapeze artist in the music halls, who had moved with some success into the garden ornaments business, before the bottom dropped out of the gnome market on the outbreak of the Second World War. By the time John Major was born in 1943, the family had suffered a severe fall in living standards, and he grew up in straitened circumstances in South London, leaving school with just three O-levels. The fact that he subsequently rose so high was entirely due to his involvement in the Conservative Party, and was seen as a fine illustration of a new meritocracy. ‘What does the Conservative Party offer a working class kid from Brixton?’ asked a Tory election poster in 1992. ‘They made him prime minister.’ In all the tribulations that were to come, he clung on to this. ‘I love my party,’ he explained in later years, contrasting himself with his predecessor. ‘She never loved the party. That was the difference.’

Major was clearly not cast in the same mould as, say, Douglas Hurd – the former Eton head boy turned diplomat, whose father and grandfather had both been MPs – rather his story seemed the living embodiment of Thatcher’s promises to those who aspired to better themselves. It was widely assumed therefore that he bought into her ideology. Certainly that was her feeling. ‘I don’t want old style, old Etonian Tories of the old school to succeed me,’ she observed. ‘John Major is someone who has fought his way up from the bottom and is far more in tune with the skilled and ambitious and worthwhile working classes than Douglas Hurd is.’

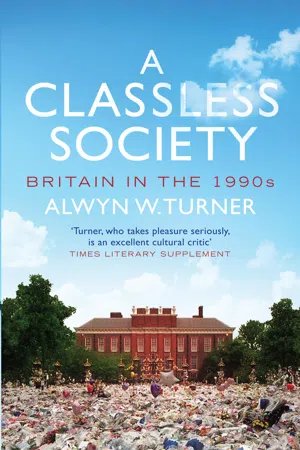

There was at least some truth in this perception. As prime minister, Major’s evocation of a classless society echoed Thatcher’s mindset, even as it pointed the way forward to Tony Blair and New Labour. ‘I want to bring into being a different kind of country,’ he said in 1991, ‘to bury forever old divisions in Britain between North and South, blue-collar and white-collar, polytechnic and university. They’re old style, old hat.’ The one-nation theme and the emphasis on newness was to become very familiar with Blair, but that specific proposal – of removing divisions in further education – was reminiscent of Thatcher’s assault on the pillars of the establishment.

It al...