eBook - ePub

Three Ways to Be Alien

Travails and Encounters in the Early Modern World

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

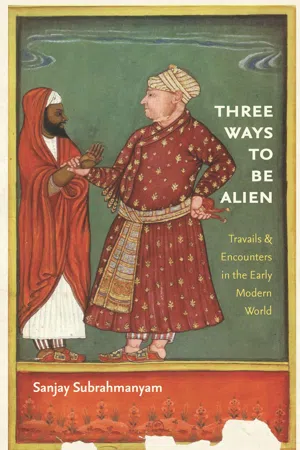

Sanjay Subrahmanyam's Three Ways to Be Alien draws on the lives and writings of a trio of marginal and liminal figures cast adrift from their traditional moorings into an unknown world. The subjects include the aggrieved and lost Meale, a "Persian" prince of Bijapur (in central India, no less) held hostage by the Portuguese at Goa; English traveler and global schemer Anthony Sherley, whose writings reveal a surprisingly nimble understanding of realpolitik in the emerging world of the early seventeenth century; and Nicolò Manuzzi, an insightful Venetian chronicler of the Mughal Empire in the later seventeenth century who drifted between jobs with the Mughals and various foreign entrepôts, observing all but remaining the eternal outsider. In telling the fascinating story of floating identities in a changing world, Subrahmanyam also succeeds in injecting humanity into global history and proves that biography still plays an important role in contemporary historiography.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Three Ways to Be Alien by Sanjay Subrahmanyam in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Brandeis University PressYear

2011Print ISBN

9781584659921, 9781584659914eBook ISBN

97816116801951 |  | IntroductionTHREE (AND MORE) WAYS TO BE ALIEN |

Why cross the boundary

when there is no village?

It’s like living without a name, like words without love.

— Tallapaka Annamacharya (fl. 1424–1503)1

CROSSING BOUNDARIES

“From the day that I returned to this country, I have had neither pleasure nor rest with the Christians and even less with the Moors [Muslims]. The Moors say I am a Christian, and the Christians say I am a Moor, and so I hang in balance without knowing what I should do with myself, save what God [Deus] wills, and Allah will save whoever has a good comportment.… Today, the knife cuts me to the bone, for when I go out into the streets, people call me a traitor, clearly and openly, and there could be no greater ill.”2 These words were apparently written in Portuguese (albeit in aljamiado, or Arabic script) by a fairly obscure Berber notable and “adventurer” in the vicinity of the port of Safi in the Dukkala region of Morocco, Sidi Yahya-u-Ta‘fuft or Bentafufa (as the Portuguese liked to term him).3 They may be found in a letter he sent to a Portuguese friend called Dom Nuno, but also in another version to the king of Portugal, Dom Manuel, sometime in late June or early July 1517, about seven months before the writer was perhaps predictably assassinated — literally stabbed in the back — in the course of a mission on behalf of his Portuguese allies by his Berber compatriots. They point to a situation where Yahya had fallen deeply and irrevocably between two (or more) stools, a process that had begun in 1506 as the Portuguese gradually moved to capture Safi and to fortify themselves there. The political and social context was undoubtedly a complex one, where different groups and interests pulled violently in varying directions. There were, to begin with, the Muslim residents of the city of Safi itself, with their own internecine quarrels. In the countryside around were both Arab and Berber clans and groups, in attitudes of lesser or greater hostility with regard to those in the town. Then we find a number of significant Jewish merchants, often refugees from Spain and Portugal, with whom Yahya was periodically accused by his rivals of being in league. At some distance, but with a lively interest in matters in Safi, were the Hintata amīrs at Marrakesh with whom Yahya was charged with carrying on a treacherous and secret correspondence where he allegedly pleaded that he was a “Moor and more than a Moor.” And finally, in Safi itself and in Portugal were the servants of the Portuguese king with whom Yahya was ostensibly allied, but who accused him periodically of all manner of ills, from exceeding his competence as a mere official and alcaide (or al-qa’id), to taking bribes, to making claims that he himself was no less than the “King of the Moors [rei dos mouros].”

What does the historian of the early modern world make of such a figure as Yahya-u-Ta‘fuft? How typical or unusual are he and his situation, and why should this matter to us? What are the larger processes that define the historical matrix within which the trajectory of such an individual can or should be read, and how meaningful is it to insist constantly on the importance of such broad processes? Should the individual and his fate be read as a mere refraction of the times, or can we tease out more from the “case study” even by the process of accumulation?4 There are no easy answers to any of the above questions, as historians working both within the domain of microhistory proper and from its fringes will gladly concede. The individual with his forensic characteristics is at one level the obvious and irreducible minimal unit for the historian of society (or what the economists might call the “primitive” for purposes of analysis); but at another level, historians in the past century have been both attracted to and repelled by the individual for methodological reasons. For those who wish to conjugate the practice of history with insights from individual psychology (and beyond that, from psychoanalysis), the central place that must be given to the individual is very nearly self-evident. Humanist traditions in history writing also remain attached to the individual figure as a peg upon which to hang much that would be difficult to set out cogently otherwise. There is also the powerful hold that biography has on the popular imagination in the past two centuries, as one can see by inspecting the shelves of the rare bookstores that can still be found today in large North American cities. Clearly readers both on university campuses and in airports would prefer a biography of President John F. Kennedy to a social history of the United States in the 1960s, or an account of the love affair (real or embroidered) of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Edwina Mountbatten to a historical account of the political dimensions of the language problem in India in the first decade after independence.

There are many from within the social sciences who have railed against this tendency, from a variety of standpoints. A long Marxist tradition of historiography asserted its opposition to the promiscuous mixing of biography and history, disdaining the former as a mere reassertion of the prejudices of writers in a somewhat heroic vein such as Thomas Carlyle.5 The thrust here was to argue that what biography fostered was a quite mistaken, and decidedly romantic, notion of historical agency, which was vested in key individuals. Late in the twentieth century, a celebrated sociologist in the Marxist tradition continued to inveigh against “the biographical illusion.”6 But historians constantly found ingenious ways around these objections, even when writing the biographies of those classic subjects, kings and emperors. Among these one can count a great medievalist’s quite recent account of the French king Saint Louis (Louis IX, 1214–70), which disarms its potential critics with the question: “Did Saint Louis [really] exist? [Saint Louis a-t-il existé?].”7 However, a set of objections were also raised from a quite different viewpoint, namely that of the early post-structuralists, with their claims in the 1960s regarding the illusive nature of the idea of authorship and their radical demotion of notions of “intention” with regard to the production of texts. If extended ever-so-slightly the dissolution of the author of a text could soon be transformed into the dissolution of the author of any act; the weight might then naturally shift to the infinite ways of reading or perceiving an act, which also rendered more or less irrelevant considerations regarding the intentions of its alleged author. The tension between structure and agency was thus radicalized, if anything, in this process. In such a context, the resort to biography could then be posed as a way of reasserting the centrality of historical agency.

But the question then arose: whose biography? A median solution may have suggested itself to social historians licking their wounds after the multipronged assault outlined above. To be sure, one could “sociologize” one’s history, resorting to descriptive statistics if not actual cliometrics, and thus make the individual and the problem of his or her historical agency disappear for a time while redefining the nature of historical inquiry as focusing on the collective or group. Or again, one could accept one of the central premises of the post-structuralist challenge and agree that history and literature were essentially not distinct; as Roland Barthes would have it, that history writing did not “really differ, in some specific trait, in some indubitably distinct feature, from imaginary narration, as we find it in the epic, the novel, and the drama.”8 What remained then would be to produce a narratological analysis of historical practice and turn the mirror on historiography itself in a sort of infinite regression. But if this did not appeal, a third solution did exist: namely to seek out the “unknown” individual, the person lambda as the French would have it, as a resolution to the structure-agency tension. Here then was a way of meeting two significant objections at the same time. First, at least on the face of it, the heroic-romantic temptation was seemingly avoided or at least postponed until the moment when the “heroism of the ordinary” as a construct might itself be called into question.9 Second, the individual in question could be made to face both ways, toward structural questions and away from them. Agency could be restored through an evocation of uncertainty, of hesitation, of the forked paths where choices needed to be made by individuals. Further, even if it contradicted the idea of the “modal biography,” the justification of the well-known microhistorian Edoardo Grendi could also be deployed in the opposite direction, by situating the individual within the category of the “exceptional normal [l’eccezionale normale],” in other words in a language that evoked the statistical distribution but also mildly subverted it.10

The debate was rendered even more complex by the interventions of scholars of literature, many associated with the movement known from the 1980s as “New Historicism.” It is to one of these, Stephen Greenblatt, that we owe the celebrated phrase “Renaissance self-fashioning,” which has very nearly been elevated to the level of a slogan in some circles. It would seem that the reference here is, in the first instance, to the far earlier claims of Jacob Burckhardt with regard to the emergence of a new sense of the individual in the context of the Renaissance, associated in turn with texts that are explicitly concerned with issues of self-presentation such as Benvenuto Cellini’s diary. Of the sixteenth-century artist and bon viveur Cellini, Burckhardt wrote in a passage that is justly celebrated: “He is a man who can do all and dares do all, and who carries his measure in himself. Whether we like him or not, he lives, such as he was, as a significant type of modern spirit.”11 One is propelled here by a sense of a powerful will, a strong sense of individuality and a freedom from the ascriptive requirements that might have mattered in an earlier, say “medieval,” social structure. Such an individual is thus able to preserve himself (or herself) in both an active and a passive-defensive mode; the latter creates the requisite freedom from ascriptive structures that might be seen as the sine qua non of the modern self, while the former is a more creative aspect, of the man “who carries his measure in himself.”12

However, a second look at notions of “self-fashioning” current in the 1980s quickly reveals how great a distance has in fact been traversed from Burckhardt. If daring and frankness may be said to characterize the Renaissance individual in the received formulation of the nineteenth-century historian, the individual engaged in “self-fashioning” seems anything but liberated from constraints. Rather, what we have is deviousness, a somewhat twisted defensive posture, a constant and nervous resort to masks of one and the other kind, as if living were an endless costume ball from which one might be summarily expelled by surly footmen. For Greenblatt, then, “in the sixteenth century there appears to be an increased self-consciousness about the fashioning of human identity as a manipulable, artful process,” a process in short that is bound up with theatrical modes of role-playing. There is more of this, for we learn too that self-fashioning “always involves some experience of threat, some effacement or undermining, some loss of self.”13 We thus come to be located, in many ways, at the very antipodes of Burckhardt’s conception of the unfettered agent “who can do all, and dares do all.”

What has transpired in the interim to transform Burckhardt’s individual who dares to paint himself in the boldest colors into Greenblatt’s feral survivors, scrabbling somewhat desperately in Renaissance society for the wherewithal to survive? The simple answer may be the intervening shadow of the Foucauldian moment. For the “self-fashioning” individual of Tudor England liberates himself from nothing; he is only passed on from one ascribed form of subservience to another, “from the Church to the Book to the absolutist state,” or from the stirrings of rebellion to an eventual acceptance of nothing more than “subversive submission.” There is a basic historical and contextual contrast that underlies this however. Clearly the Italy of fragmented states in the sixteenth century was anything but an all-powerful absolutist monarchy. Whoever individuals such as Cellini had to answer to, it was not to the likes of Queen Elizabeth or, a half century later, Cromwell. A large weight is thus placed on transformations in the nature of the sixteenth-century state as a regulatory and disciplining institution in order to explain the particular forms that “self-fashioning” took under the Tudors. Little wonder then that we have the following lapidary phrase from the pen of Greenblatt: “we may say that self-fashioning occurs at the point of encounter between an authority and an alien.”14

Where does such a discussion leave us with respect to an understanding of the figure with whom we began: Sidi Yahya-u-Ta‘fuft of Safi? The historiography already offers us a variety of solutions. A leading scholar of sixteenth-century Morocco sums up the matter thus from the relatively dispassionate perspective of political economy.

[I]n the first decades of the 16th century, Portuguese administrators relied heavily on the services of allied tribal leaders to exploit inland areas economically dependent on the ports of Safi and Azemmour. Occasionally, they went so far as to appoint a local ruler by royal decree when it suited them. The most notorious example of such a ruler was Yahya-u-Ta‘fuft (d. 1518), a Berber adventurer from the village of Sarnu near Safi who was brought to power by a Portuguese-engineered coup that ousted the previously dominant Banu Farhum family. As qa’id of the city and its rural periphery, Yahya-u-Ta‘fuft was paid a yearly salary of 300 mithqāls (about 30 ounces) of gold plus one-fifth of the booty taken in raids conducted against tribes considered to be hostile to Portugal. In addition, he could count on approximately 10,000 mithqāls in bribes or “donations” from merchants and other individuals seeking his aid or protection.15

The same historian then goes on to detail the various abusive practices of Yahya and his like: first, their use of a “band of mercenaries” who collected taxes from village and tribal lands and punished pastoralists through “brutal and destructive raids,” thus using their alliance “with the Portuguese to amass large fortunes”; second, the fact that Yahya directly trivialized the “form and content of Islamic law in the region,” by arrogating to himself “the authority to promulgate a personal qānūn, or extra-Islamic body of regulations, that took precedence over all other forms of legality”; and finally, his collaboration with the “legendary captain Ataide of Safi” in order to organize raids as far as Marrakesh, where “Yahya-u-Ta‘fuft’s men insolently banged their spears on the locked gates of the half-deserted city that had once been the capital of the mighty Almohad empire.” Yahya is thus clearly seen to be an accomplice, if not more, in “the short-sighted and rapacious policies of both the Portuguese crown and the captains who served in the region [which] significantly contributed to the ruin of Portugal’s African commercial empire by destroying the stability of the local Moroccan socioeconomic structures upon which the supply of goods guaranteeing its African trade network depended.”

This macroscopic vision gives us limited insights into what might have been the lived world of such a man, let alone what might have prompted him to write lines such as those with which this introduction commenced. This Yahya might have had problems with local Muslims, but surely he should have been well treated by the Portuguese, for whom he was apparently an agent, a comprador of sorts. A rather different reading from that presented above is available to us in a more recent study, focusing on the question of “honor” in general, and the rivalry between Yahya and the Portuguese captain of Safi, Nuno Fernandes de Ataíde, more particularly.16 We are reminded that in spite of the fact that he spent two long sojourns in Portugal (from 1507 to 1511, and again from 1514 to 1516), and that he appears to have gained direct access to the king, Dom Manuel, Yah...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword by David Shulman

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: Three (and More) Ways to Be Alien

- 2 A Muslim Prince in Counter-Reformation Goa

- 3 The Perils of Realpolitik

- 4 Unmasking the Mughals

- 5 By Way of Conclusion

- Notes

- Index